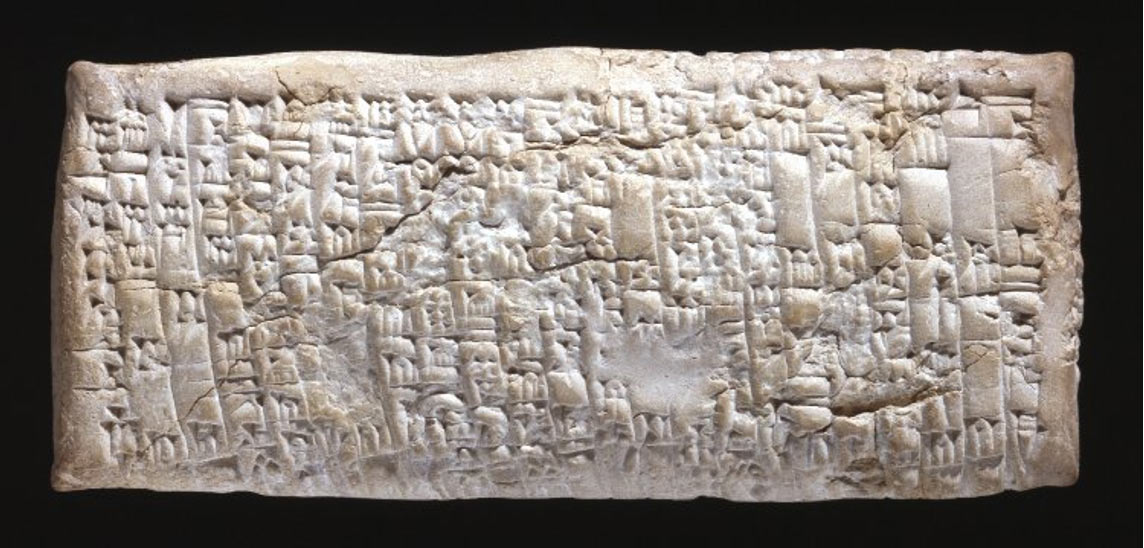

A clay tablet from ancient Babylon reveals that no matter where (or when) you go, good customer service can be hard find. So it was revealed by the irate copper merchant, Nanni, in 1750 B.C. The merchant’s aggravation is evident, spelled out in cuneiform on a clay tablet now displayed in The British Museum.

In what is said to be the oldest customer service complaint discovered, Babylonian copper merchant Nanni details at length his anger at a sour deal, and his dissatisfaction with the quality assurance and service of Ea-nasir.

Forbes reports, “The letter implies that Nanni had dispatched his personal assistants to Ea-nasir Fine Copper at least once looking for a refund, only to be rebuffed and sent home empty handed – and through a war zone!”

MORE

According to science site ABC Science, a translation of the tablet text is available in the book “Letters from Mesopotamia: Official, Business and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millenni” by Assyriologist A. Leo Oppenheim. The book includes translations of letters written in ancient Akkadian from many walks of life; “from poverty-stricken women to their generous brothers, from pregnant slave girls and yes, between merchants, manufacturers and traders.”

The translation lays out Nanni’s displeasure:

“Tell Ea-nasir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows : “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe(?) you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and umi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Samas.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full.

Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.”

The complaint letter, written 3,750 years ago was found at the city of Ur. Ur (present day southern Iraq) was one of the most important Sumerian city-states in ancient Mesopotamia in the third millennium B.C. Mesopotamian society was an advanced culture. They had knowledge of medicine, astronomy and agriculture, and had invented technologies such as glass-making, irrigation, textile weaving and metal working, notes ABC Science.

MORE

The ancient system of writing called cuneiform involved pressing patterns into soft clay tablets by means of a stylus, generally a blunt reed or stick. The scribe would use the stylus to create wedge-shaped markings in the clay, and the soft tablet was then fired to preserve the message. Cuneiform writing died out as it was replaced with the Phoenician alphabet around 200 A.D, and it became a lost written language. It was deciphered by modern researchers in the 19 th century.

A sample of cuneiform from an extract from the Cyrus Cylinder (lines 15–21), giving the genealogy of Cyrus the Great and an account of his capture of Babylon in 539 B.C.E.

Because the writing system was used for more than three millennium, there remain many preserved samples of such tablets. The BAS Library reports that there are close to half a million cuneiform tablets in the world’s museums, but only 30,000 to 100,000 have been translated.

Cuneiform inscription by Xerxes the Great on the cliffs below Van castle, Turkey. It’s several meters tall and wide, 25 centuries old, and the message comes from the Persian king Xerxes. Wikimedia Commons.

It reads in part:

The king Xerxes says: the king Darius, my father, praised be Ahuramazda, made a lot of good, and this mountain, he ordered to work its cliff and he wrote nothing on it so, me, I ordered to write here.

MORE

Archaeologists have discovered countless other ancient tablets revealing much about the beliefs and lifestyles of various historic cultures. Curse tablets were attempts to hamper or harm enemies, while other tablets recorded beautiful ancient songs. The Babylonian Cyrus Cylinder is believed to be an ancient declaration of early human rights.

It is fascinating to see an ancient artifact— an item so rare, delicate, and important that we protect it at all costs—detailing the comical mundanity of life and everyday business. It is interesting to read about the workings of ancient trade and war via first-hand testimony. Finally, it is surprising to see that humanity, through thousands of years, hasn’t changed much at all. To this day we still fire off letters, tweets and emails to businesses that we feel haven’t provided the best service. Will our descendants in 4000 years’ time be reading our current-day complaints?

Featured Image: Clay tablet; letter from Nanni to Ea-nasir complaining that the wrong grade of copper ore has been delivered after a dangerous voyage, misdirection, and delays. © The Trustees of the British Museum

By Liz Leafloor