The Assyrian Sculpture Court | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Assyrian Sculpture Court (Gallery 401) displays sculptures from the Assyrian capital city of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) in a space designed to evoke their original palace setting. The room is not a full reconstruction: many aspects of the palace’s original appearance remain unknown, and the sculptures themselves come originally from multiple rooms, although together they are representative of the way in which many rooms in the palace were decorated.

The ancient state of Assyria lay in what is now northern Iraq. The sculptures in the gallery all date to the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), a king whose military expeditions to the west reached the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, and helped lay the foundations for an empire that came to dominate the Near Eastern political landscape from the ninth through seventh centuries B.C. The king himself is depicted on one of the reliefs (32.143.4). Ashurnasirpal moved from the traditional Assyrian capital, Ashur, to Nimrud, and there built a new and spectacular palace, today called the Northwest Palace for its position on the site’s citadel. Texts survive describing the palace’s completion and inauguration, involving a banquet for almost 70,000 people. The number is probably exaggerated, but there is no doubt that this was a huge festival.

Like most ancient Near Eastern palaces, the Northwest Palace was made of mud brick. Ashurnasirpal seems to have been the first Assyrian king to line his palace walls with stone bas-reliefs, and his inscriptions boast of finding and utilizing the stone that made it possible. This stone, which could be quarried locally, is a gypsum, sometimes called alabaster (it is almost white when first cut) and colloquially known as “Mosul marble” after the nearby modern city. The slabs are extremely heavy, and simply quarrying and transporting the stone for use in the palace was a major undertaking. Once in position, the carving of the reliefs, with their carefully modeled figures and perfectly smooth backgrounds, represented another enormous task. An inscription describing the king’s achievements, today called the Standard Inscription, was carved across the center of each panel. It seems likely that the repetition of the inscription, like that of the reliefs’ imagery, formed part of the magical protection of the palace and the king. Finally, the reliefs were brightly painted. Some pigment can still be seen in rare cases (31.72.1 ), and analysis of microscopic traces can sometimes reveal the original colors even when no paint is visible. Many of the figures in the reliefs wear clothes with embroidered patterns, rendered on the stone as fine engraving (1982.1188.4 ); these would originally have been picked out in contrasting colors.

Originally the palace rooms were richly furnished, though sadly it is difficult to reconstruct this aspect of their original appearance. Typically the wooden frames of furniture do not survive. Decorative elements in ivory have been found in large quantities (59.107.3 ), though most of these are of non-Assyrian style: they may have come to Nimrud as tribute or war booty, and to what degree they were actually used as palace furniture at Nimrud is debated. Furniture is also sometimes depicted in art. Similarly, textiles such as rugs and wall hangings do not survive themselves but are sometimes shown in other media, including stone doorsills carved with carpet designs (X.153).

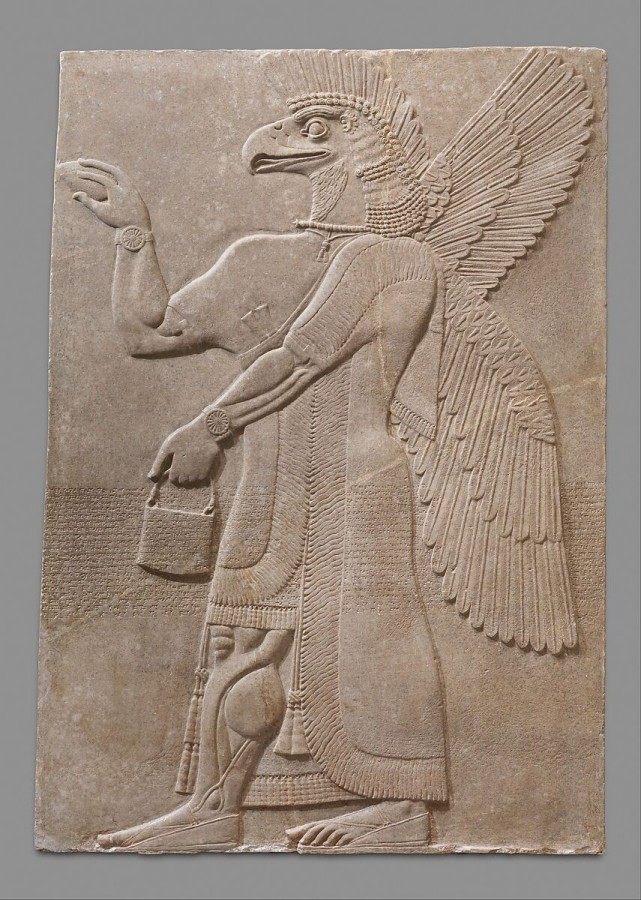

The reliefs in the Assyrian Sculpture Court come originally from several different rooms in the palace, but they give a good general impression of a single room filled with protective imagery. Most rooms in the palace were decorated in this way, though in the throne room more space was given to scenes of war and hunting. Most of the reliefs show human- or eagle-headed supernatural figures, whose function was to provide magical protection to the palace and the king. Although the figures are repeated many times through the palace, there are many subtle variations in their dress and appearance, and no two are truly identical.

The reliefs in the Assyrian Sculpture Court come originally from several different rooms in the palace, but they give a good general impression of a single room filled with protective imagery. Most rooms in the palace were decorated in this way, though in the throne room more space was given to scenes of war and hunting. Most of the reliefs show human- or eagle-headed supernatural figures, whose function was to provide magical protection to the palace and the king. Although the figures are repeated many times through the palace, there are many subtle variations in their dress and appearance, and no two are truly identical.

We have little information on the planning and composition of the relief program, though it seems that the dominant concerns were magical and religious. The placement of stylized “sacred tree” imagery at the corners of many rooms reflects a belief that corners, like doorways, were sensitive and vulnerable to demonic intrusion. It is at the entrances and corners of rooms and buildings that apotropaic figurines were often buried.

At one end of the gallery stand a colossal winged, human-headed bull and lion, two of many that stood as guardians in the palace, confronting visitors and helping to ward off evil spirits and demons. Normally these protective figures stood in gateways, facing out onto courtyards. An exception was the throne room, at one end of which stood two winged lions facing inward, as the winged bull and lion do in the gallery, separating the throne room from an antechamber. The bull and lion now in The Metropolitan Museum originally formed part of two gateways in a courtyard. In antiquity, each gateway was guarded by a matching pair, either two bulls or two lions.

Many floor tiles have been found in Assyrian palaces; the modern floor tiles in the gallery match these in size and appearance. Many of the ancient tiles bore inscriptions on their edges, hidden in the floor and thus visible only to the gods. Above the reliefs and in other areas, surviving fragments of painted plaster and brick decoration (57.27.28 ) reveal that the walls were painted with both geometric and figural designs. The ceilings were made using great beams of cedar wood from Lebanon (echoed in the roof beams of the gallery), overlaid with reed matting and mud plaster. Some of these rooms were enormous, and roofing them represented a real technical challenge: the throne room, in particular, was 154 feet long and 33 feet across. The gallery is the width of the throne room but far shorter in length.

Two reliefs in the gallery, positioned next to the winged bull and lion, come not from the Northwest Palace but from the nearby temple of the warrior god Ninurta (32.143.9 ; 32.143.10 ). Above each is a replica, and the original reliefs and replicas together are arranged to evoke the facade and entrance of the Ninurta temple, where the originals flanked winged-lion guardian figures. These and the lower part of one other relief are the only replicas in the room; all the other sculptures are the ninth-century B.C. originals. They were excavated in the mid-nineteenth century, in some of the very first excavations of ancient Mesopotamian objects. At that time, nothing like the reliefs found at the Assyrian sites of Nimrud, Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin), and Nineveh had been seen in well over 2,000 years, so that although Assyria appears prominently in the Bible and in Classical texts, no one in the modern world had seen Assyrian palace art or architecture, or knew what it might look like.

Citation

Seymour, Michael. “The Assyrian Sculpture Court.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nimr_2/hd_nimr_2.htm (December 2016; updated January 2022)

Further Reading

Aruz, Joan, Sarah B. Graff, and Yelena Rakic, eds. Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.

Cohen, Ada, and Steven E. Kangas, eds. Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2010.

Crawford, Vaughn E., Prudence O. Harper, and Holly Pittman. Assyrian Reliefs and Ivories in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Palace Reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and Ivory Carvings from Nimrud. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980.

Curtis, John E., and Julian E. Reade, eds. Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.

Curtis, John E., et al. New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference 11th–13th March 2002. London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2008.

Oates, Joan and David Oates. Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2001.

Russell, John Malcolm. From Nineveh to New York: The Strange Story of the Assyrian Reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum and the Hidden Masterpiece at Canford Manor. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Additional Essays by Michael Seymour

- Seymour, Michael. “Babylon.” (June 2016)

- Seymour, Michael. “Nimrud.” (November 2016)

- Seymour, Michael. “Nineveh.” (September 2017)

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!