Egyptian Archaeologists Uncover a ‘Startling’ Mummy That Survived Nearly 4,000 Years

Tomb secrets: The FBI cracks the DNA code on an ancient Egyptian mummy

After other teams of scientists tried fruitlessly to extract DNA from the remains, the FBI made a surprising discovery

The severed, mummified head was discovered in an Egyptian tomb in 1915. Now, its much speculated identity has been revealed (Wikimedia Commons)

The severed, mummified head was discovered in an Egyptian tomb in 1915. Now, its much speculated identity has been revealed (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1915, a team of US archaeologists excavating the ancient Egyptian necropolis of Deir el-Bersha blasted into a hidden tomb. Inside the cramped limestone chamber, they were greeted by a gruesome sight: a mummy’s severed head perched on a cedar coffin.

The room, which the researchers labelled Tomb 10A, was the final resting place for a governor named Djehutynakht (pronounced juh-HOO-tuh-knocked) and his wife. At some point during the couple’s 4,000-year slumber, grave robbers ransacked their burial chamber and plundered its gold and jewels. The looters tossed a headless, limbless mummified torso into a corner before attempting to set the room on fire to cover their tracks.

The archaeologists went on to recover painted coffins and wooden figurines that survived the raid and sent them to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1921. Most of the collection stayed in storage until 2009 when the museum exhibited them. Though the torso remained in Egypt, the decapitated head became the star of the showcase. With its painted-on eyebrows, sombre expression and wavy brown hair peeking through its tattered bandages, the mummy’s noggin brought viewers face to face with a mystery.

“The head had been found on the governor’s coffin, but we were never sure if it was his head or her head,” says Rita Freed, a curator at the museum.

The museum staff concluded only a DNA test would determine whether they had put Mr or Mrs Djehutynakht on display.

“The problem was that at the time in 2009 there had been no successful extraction of DNA from a mummy that was 4,000 years old,” Freed says.

Egyptian mummies pose a unique challenge because the desert’s scorching climate rapidly degrades DNA. Earlier attempts at obtaining their ancient DNA either failed or produced results contaminated by modern DNA. To crack the case, the museum turned to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The FBI had never before worked on a specimen so old. If its scientists could extract genetic material from the 4,000-year-old mummy, they would add a powerful DNA-collecting technique to their forensics arsenal and also unlock a new way of deciphering Egypt’s ancient past.

“I honestly didn’t expect it to work because at the time there was this belief that it was not possible to get DNA from ancient Egyptian remains,” says Odile Loreille, a forensic scientist at the FBI. But in the journal Genes in March, Loreille and her colleagues reported that they had retrieved ancient DNA from the head. And after more than a century of uncertainty, the mystery of the mummy’s identity had been laid to rest.

What lies in Tomb 10A

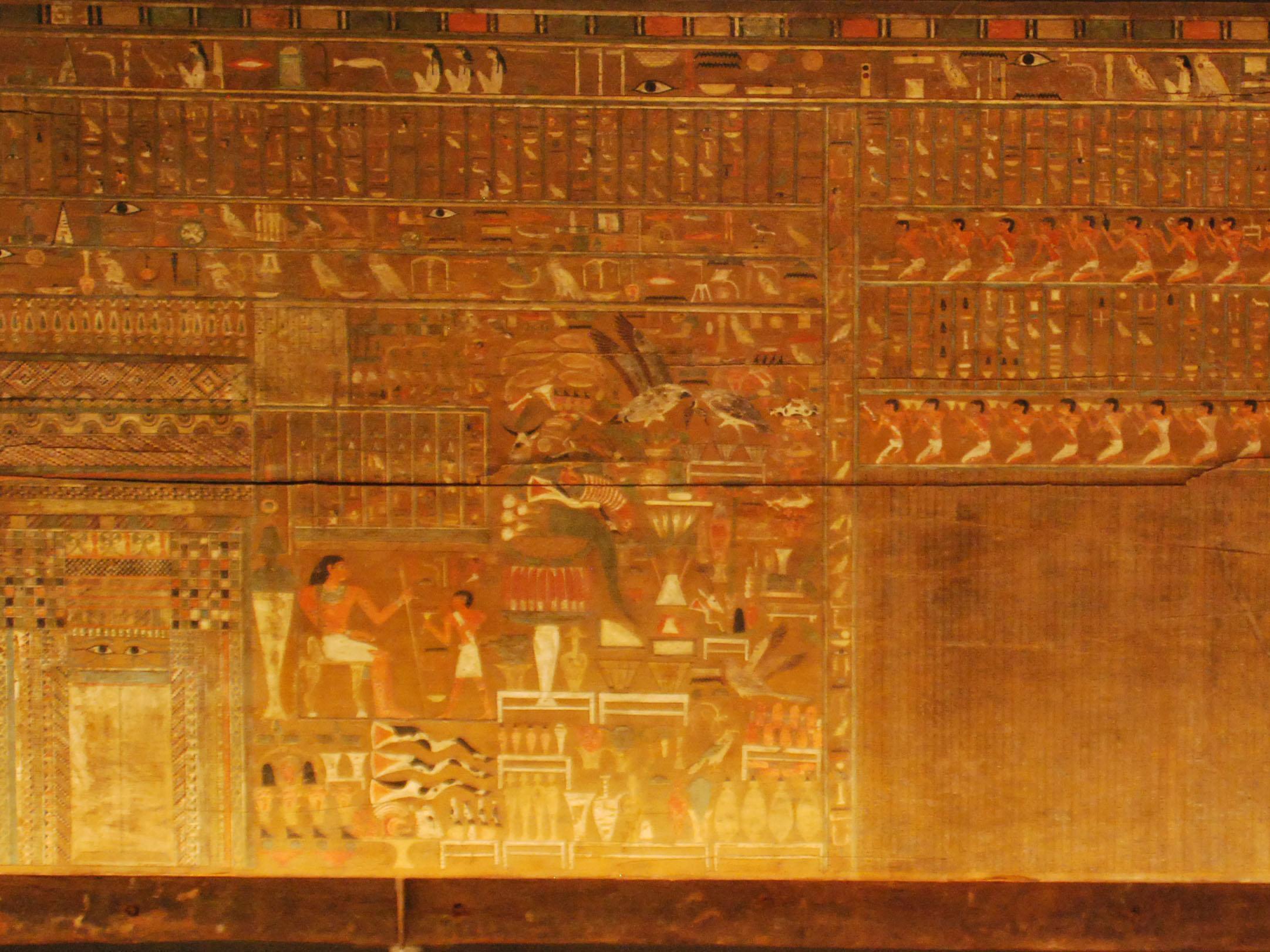

Djehutynakht and his wife, Lady Djehutynakht, are believed to have lived around 2000BC during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. They ruled a province of Upper Egypt. Though the walls in their tomb were bare, the coffins were embellished with beautiful hieroglyphics of the afterlife.

“His coffin is a classic masterpiece of Middle Kingdom art,” says Marleen De Meyer, assistant director for archaeology and Egyptology at the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo, who re-entered the tomb in 2009. “It has elements of a rare kind of realism.”

The team that discovered Djehutynakht’s desecrated chamber more than a century ago was led by the archaeologists George Reisner and Hanford Lyman Story. As they explored the cliffs of Deir el-Bersha, which is about 180 miles south of Cairo on the east bank of the Nile, they uncovered a 30-foot burial shaft beneath boulders. With the help of dynamite, they entered the tomb.

In their original reports, the archaeologists said that the dismembered body parts belonged to a woman, presumably Lady Djehutynakht. De Meyer suspected that the head belonged to the governor and not his wife.

The outer coffin of Governor Djehutynakh, found in Deir el-Bersha, in a tomb known as 10A (Wikipedia Commons)

Missing facial bones

As Freed prepared the items from Tomb 10A for exhibition in 2005, she reached out to Massachusetts General Hospital. Its CT scan revealed the head was missing cheek bones and part of its jaw hinge – features that may have potentially provided insight into the mummy’s sex.

“From the outside, you could not tell that the mummy had been so internally tinkered with,” says Dr Rajiv Gupta, a neuroradiologist at Massachusetts General. “All the muscles that are involved in chewing and closing the mouth, the attachment sites of those muscles had been taken out.”

They now had another mystery: why did the mummy have these facial mutilations?

Along with Dr Paul Chapman, a neurosurgeon at the hospital, Gupta hypothesised that they might be part of an ancient Egyptian mummification practice known as the “opening of the mouth ceremony”. The ritual was performed so the deceased could eat, drink and breathe in the afterlife.

“It’s a very specific cut they made,” says Gupta, referring to the surgical removal of the coronoid part of the mandible. “There’s a precision to it which is what we were surprised by. Someone was actually doing coronoidectomy 4,000 years ago.”

Some doctors and Egyptologists doubted that ancient Egyptians could perform that complex operation with primitive tools.

To show it was possible, Gupta, Chapman and an oral and maxillofacial surgeon performed the bone removal on two cadavers using a chisel and mallet. They drove the chisel between the lips and gums behind the wisdom teeth, and were able to remove the same bones missing in the mummified skull.

Still, the question of the mummy’s identity lingered.

Deir el-Bersha, located on the east bank of the Nile in the Minya Governorate (Alamy)

Deir el-Bersha, located on the east bank of the Nile in the Minya Governorate (Alamy)

Tooth raiders

The doctors and museum staff determined their best chance of retrieving DNA would be by extracting the mummy’s molar. “The core of the tooth was where the money was,” Chapman says. Teeth often act as tiny genetic time capsules. Researchers have used them to tell the tales of our prehistoric human cousins called Denisovans, as well as to provide insight into the medical history of long-dead people.

“The advantage we had is that we had a hole in the neck because the head had been torn off,” says Chapman.

They snaked a long scope with a camera into the back of the mouth. The first tooth they targeted would not budge, so Dr Fabio Nunes, who was then a molecular biologist at Massachusetts General, switched to a different molar. Sweating, he clamped down with dental forceps, gave it a few wiggles, then a few twists and “pop” – it was free.

“My main concern was: don’t drop it, don’t drop it, don’t drop it,” he says. After he successfully manoeuvred out from the neck, the room exhaled and gazed upon the prize.

“This looked like an absolutely cavity-free, perfectly preserved tooth,” Freed says. “I thought maybe it was Mrs Djehutynakht who had died in childbirth. Total speculation.”

FBI tackles an ancient forensic case

For several years, other teams of scientists tried fruitlessly to get DNA from the molar. Then the crown of the tooth went to Loreille at the FBI’s lab in Quantico, Virginia, in 2016.

Loreille had joined the FBI after 20 years of studying ancient DNA. Previously, she had extracted genetic material from a 130,000-year-old cave bear, and worked on cases to identify unknown Korean War victims, a two-year-old child who had drowned on the Titanic and two of the Romanov children who were murdered during the Russian Revolution (though she was unable to confirm if one was the famed Anastasia).

In the FBI’s lab, Loreille drilled into the tooth’s core and collected a tiny bit of powder. She then dissolved the tooth dust to make a DNA library that allowed her to amplify the amount of DNA she was working with, like a copy machine, and bring it up to detectable levels.

To determine whether what she had extracted was ancient DNA or contamination from modern people, she analysed how damaged the sample was. It showed signs of heavy damage, confirmation that she was studying the mummy’s genetic material.

She plugged her data into computer software that analysed the ratio of chromosomes in the sample. “When you have a female you have more reads on X. When you have a male you have X and Y,” she says.

The program spat out “male”.

Loreille discovered the mummified severed head had indeed belonged to Djehutynakht. In doing so, she had helped establish that ancient Egyptian DNA could be extracted from mummies.

“It’s one of the Holy Grails of ancient DNA to collect good data from Egyptian mummies,” says Pontus Skoglund, a geneticist at the Francis Crick Institute in London who helped confirm the accuracy of the finding while he was a researcher at Harvard. “It was very exciting to see that Odile got something that looked like it could be authentic ancient DNA.”

Model of a procession of offering-bearers from the tomb of Governor Djehutynakht (Wikipedia Commons)

Unravelling a mummy’s genetic history

Loreille’s examination also showed that Djehutynakht’s DNA carried clues to another mystery. For centuries, archaeologists and historians have debated the origins of the ancient Egyptians and how closely related they were to modern people living in North Africa. To the researchers’ surprise, the governor’s mitochondrial DNA indicated his ancestry on his mother’s side, or haplogroup, was Eurasian.

“No one will ever believe us,” Loreille recalls telling her colleague Jodi Irwin. “There’s a European haplogroup in an ancient mummy.”

Irwin, the supervisory biologist at the FBI’s DNA support unit, had similar concerns. To verify the results, they sent a portion of the tooth to a Harvard lab, and then to the Department of Homeland Security, for further sequencing.

Then last year as the FBI scientists worked to confirm their results, another group affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany reported the first successful extraction of ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies. Their results showed that their ancient Egyptian samples were closer to modern Middle Eastern and European samples than to modern Egyptians, who have more sub-Saharan African ancestry.

“It was at the same time ‘Dang! We’re not first,’” Loreille says. “But also we’re happy to see they also had this Eurasian ancestry.”

Alexander Peltzer, a population geneticist at the Planck Institute and an author on the first Egyptian mummy DNA paper, says that Loreille’s genetic findings fit well with what his team had found.

“Of course, one has to be careful to deduce too much from single genomes and only two locations,” he says.

Irwin also expressed caution with how the public interprets her team’s results, saying that mitochondrial DNA provides “just a very small glimpse into somebody’s ancestry”.

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!