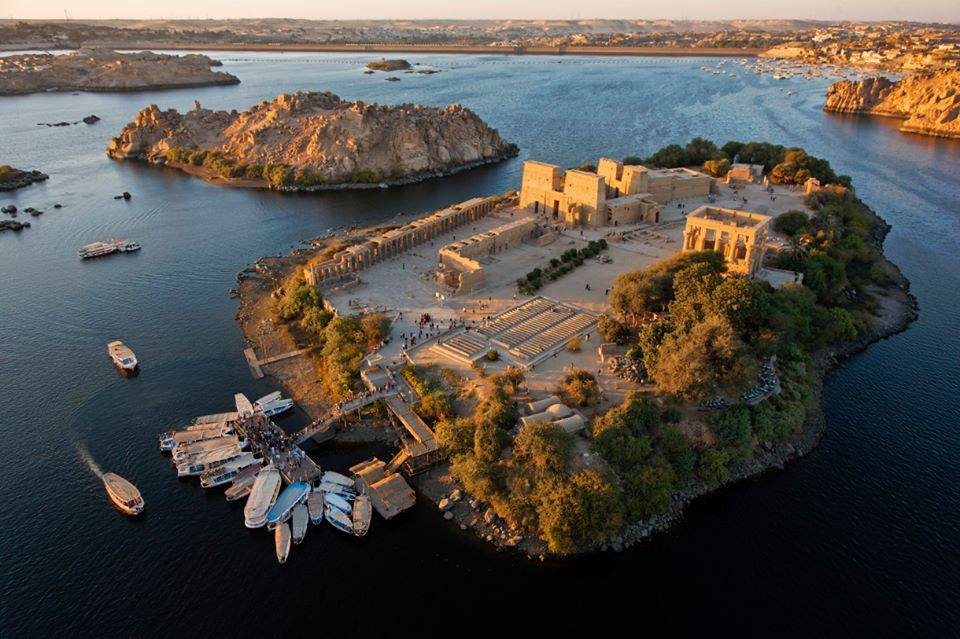

The tiny island of Philae, a mere 450 metres long and less than 150 metres wide

The tiny island of Philae, a mere 450 metres long and less than 150 metres wide, captured the imagination of countless travellers to Egypt from early times. It was famed for its beauty and was known as the “Pearl of Egypt’. Plants and palm trees grew from the fertile deposits that had collected in the crevices of the granite bedrock. Gracious Graeco-Roman temples and colonnades, kiosks and sanctuaries rose proudly against the skyline. There was a sense of mystery. Not furtive, in violate secrets, so much as veiled mystification.

The sanctity of Philae during the Graeco-Roman period outrivalled many of the other cities of Egypt. It had become the centre of the cult of Isis, which was revived during the Saite period (664-525 BC). The Ptolemies, as already noted, sought to please the Egyptians by building temples to their most beloved gods and goddesses.

Ptolemy II (285-246 BC) started construction of the main Temple of Isis. temple to her consort, Osiris, was built on a neighbouring island, Bigeh (only a portal of which remains). Their son Horus, or Harendotus as he was called by the Ptolemies, had a temple of his own on Philae. Other structures on the island included a small temple to Imhotep, builder of Zoser’s Step Pyramid at Sakkara, who was later deified as a god of medicine, and temples to two Nubian deities: Mandolis and Arhesnoter.

Philae was situated south of Aswan and, therefore, strictly belonged to Nubia. Isis was worshipped by Egyptians and Nubians alike. Fantastic tales were told of her magical powers. It was believed that her knowledge of secret formulae had brought life back to her husband Osiris; that her spells had saved her son Horus from the bite of a poisonous snake; and that she was the protectress of all who sought her. Countless visitors came to the island, where the priests, appropriately clad in white vestments, claimed a knowledge of the mysteries. With carefully rehearsed liturgies and the necessary symbolism, they drew hordes of faithful. If these visitors were lucky they could view the image of the goddess during the spring and autumn festivals in her honour. This was when the death and resurrection of Osiris was enacted, in which Isis played a major role. It was Isis who found the body of her husband that had been locked in a chest and cast on the Nile by his wicked brother Set. It was she who made the body whole through her prayers. It was she who knew the secrets, the spells, and even the name of the Sun-god. Isis was the great goddess; she was at once mother-goddess and magician. It was believed that her single tear, shed for Osiris, caused the annual flood, which brought life to the land.

The myth of Osiris and Isis had, by this time been enlarged and embellished countless times. In one version the coffin containing the body of Osiris was swept out to sea, and came to rest on the Phoenician coast where a tamarisk tree enclosed the entire coffin in its trunk. The king of Byblos, who needed a strong prop for the roof of his palace, ordered the tree to be cut down. Were it not for the fact that the tree gave off a sweet-smelling odour, which spread across the Mediterranean, and reached Isis, she would never have been able to trace the body of her husband. She set off for Byblos without delay and, disguised as a nurse, she took charge of the newborn son of the king. When she finally revealed who she was, and the reason for her being there, the king gave her the miraculous tree containing the coffin, and she took the body of Osiris back to Egypt. This was when Set found it, and cut it to pieces.

Once established on the island of Philae, the priests lost no time in laying claim to additional territory: over eighty kilometres lying to the south of Seheil island. They found an ancient tradition on which to base their claim. In a forged inscription inscribed high on the rocks of Seheil, is a record of how a governor of Elephantine appealed to the pharaoh Zoser (builder of the Step Pyramid some 2,500 years earlier) because of his concern for the people following years of famine. Zoser responded by enquiring about the sources of the Nile and asked whether the governor knew which god controlled its waters. The governor promptly responded that it was Khnum of Elephantine but that he was angry because his temple had been allowed to fall to ruin. Zoser forthwith issued a decree granting a Targe tract of land to Khnum and levying a tax on all those who lived on the produce of the river, fishermen and fowlers alike, for the benefit of the priests of Khnum. It was this land that the priests of Philae claimed had been granted to them by the pharaoh Zoser, and for the same reason: to put an end to the famine that had been raging for seven long years. The taxes on fishermen forth with went to their benefit.

Each day the priests would wend their solemn way into the holy precincts of the temple of Isis with incense and burnt offerings. The statue of the goddess would be ceremoniously washed, clothed and adorned. Service after service, ritual after ritual, with humility, chanting and prayer, she would be suitably appealed to and adored until such time as she was undressed, washed again, derobed and replaced in the sanctuary until the following morning.

Little wonder that with such pageantry, with priests shuffling between columns, pouring libations on sacred altars, and swearing to direct communication with the gods, the site should attract curious visitors along with the faithful. Sightseers came in such number as to disturb the priests of Philae. On the base of two granite obelisks found on the island are inscriptions addressed to Ptolemy IX (171-163 BC), his wife and sister, both of whom were called Cleopatra; they complained that:

…. travellers who visit Philae, generals and inspectors … chief officers of the police … the armed guards who are following, and the rest of their servants, compel us to pay the expenses of their maintenance while they are here, and by reason of this practice the temple is becoming very poor and we are in danger of coming to possess nothing… We beseech you … that you give command not to annoy us with these vexations … to give us a written decision’.”

A second inscription shows that their wishes were granted, and a third indicates satisfaction at the arrangements made to safeguard them from annoyance.

These Greek and hieroglyphic inscriptions on the base of the obelisks played a part in the decipherment of hieroglyphics. The Rosetta Stone alone was not the key, despite its three copies of a single text in hieroglyphics, demotic and Greek that led to the identification of the word “Ptolemy’. William Bankes, an English traveller, scholar and collector, to whose estate the obelisk was taken (having been retrieved by Giovanni Belzoni), sent copies of the Greek and Egyptian texts to different scholars, pointing out the hieroglyphic form of ‘Cleopatra’. These two names, and others, eventually made it possible to identify seventeen of the twenty-five letters of the hieroglyphic alphabet. The obelisk now stands in the park of Bankes’s house at Kingston Lacy in Dorset, England.

Building operations on Philae continued throughout the Roman period. There seems to have been an effort to indicate both continuity of rule, and also to retain the support of the powerful priests on the island near the southern frontier. It was at this time that Plutarch, the Greek writer, came to Egypt, and combined the many variations of the Osiris myth, from the earliest version) to the later, into a coherent tale. By this time Osiris had become the just and wise ruler, not of Egypt alone, but of the whole world. He left Egypt under the wise council of Isis, and, accompanied by Thoth, Anubis and Wepwawat, he set off to conquer Asia. He returned to Egypt only after he had spread civilization, peacefully, with song and music, far afield. It has been suggested that this aspect of the myth so closely resembles the stories of Dionysus and Orpheus that Plutarch may have been influenced by them.

The access to the island was enlarged on its northern side by Diocletian, in whose reign the Christians were persecuted. It is ironical that this uniquely picturesque sanctuary was the only peaceful spot in an area that had known nothing but strite from the Persian period (525 BC) onwards. The Meroitic Kingdom had spread northwards and challenged Egypt. Desert tribes, known as the Blemmys and the Nobadai, who habitually warred with one another, made their appearance around Aswan and terrorised Upper Egypt. There was no security along the frontier.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the island of Philae, isolated and protected from attack and showing a spirit of tolerance to the worship of various gods, should develop a conciliatory character. It was chosen as the venue for the signing of peace treaties; Augustus, the first Roman emperor of all Egypt, ordered his prefect to come to terms with representatives of the Meroitic Kingdom, and the meeting took place on Philae; later, negotiations were conducted there between Roman officials and the Blemmys. It is noteworthy, however, that even in times of conflict, the priests of the Blemmys were given right of entry to the island, and they came in peace.

Garrisons and treaties notwithstanding, the attacks of the Blemmys were renewed year after year. Finally, Diocletian considered it a waste of manpower to keep soldiers stationed in a nonrevenue raising area. He ordered their withdrawal. But not before inviting the Nobadai, the long-standing enemies of the Blemmys, to settle in the area and act as a buffer. The Nobadai were provided with a subsidy for their services and the fortifications were strengthened.

As so often happens, a common enemy breeds understanding. The Nobadai and the Blemmys reasoned that nurturing hostility towards one another was getting them nowhere. If they united their forces and attacked Roman Egypt, they might benefit. This they did. Only when Christianity officially came to Egypt under Theodosius (AD 379-395), were the two tribes driven out. The Blemmys, however, obtained permission to visit the temple of Isis for certain festivities and, once a year, to borrow the sacred statue of the goddess to consult the oracle.

From a Greek inscription in the seclusion of the Osiris shrine above the sanctuary of the temple of Isis, we learn that in AD 453 the goddess Isis was still worshipped by the Blemmys and their priests. This was long after the edict of Theodosius declared that pagan temples should be closed.

Thus, just as Abydos stands at the beginning of pharaonic history, having given rise to the Thinite kings who first united the Two Lands into a single state, Philae stands at the end, as the last outpost of ancient Egyptian tradition on its native soll. In the reign of Justinian (AD527-565) Narsus finally closed the temple and transported statues of some of the deities to Constantinople.

Saving the monuments of Philae

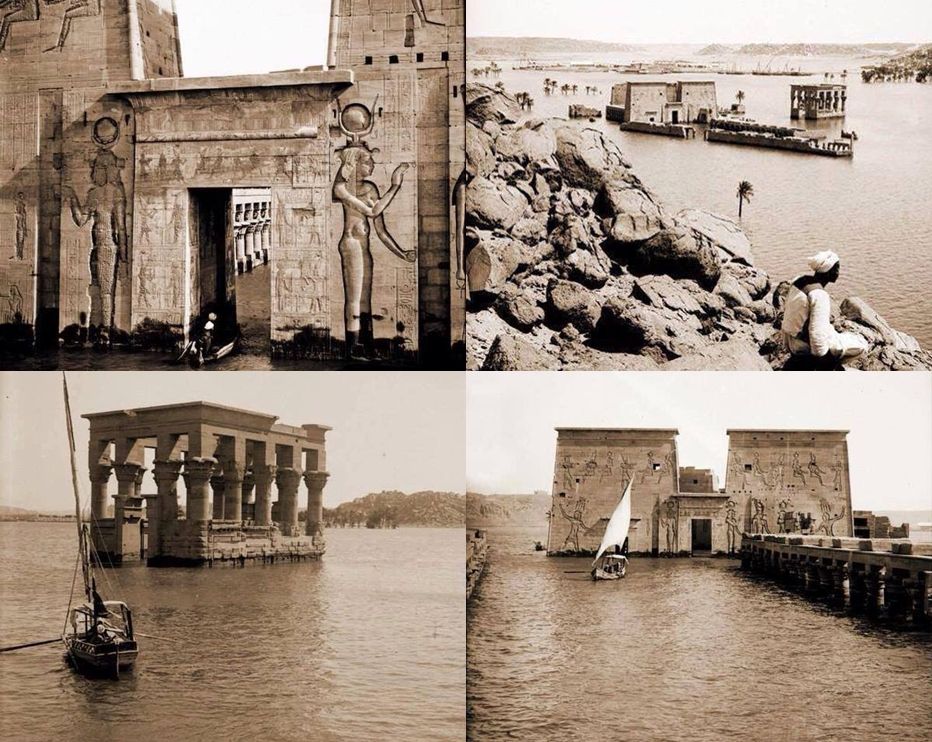

The first Aswan Dam (El Khazan) was built between 1898-1902. This was when Philae was first threatened. Poets and writers lamented its destiny but their words fell on deaf ears. Between 1907-1912 the dam was heightened, and fears for the remains of all Nubia were voiced. The Egyptian Government set aside funds to survey, record and, whenever possible, excavate the endangered areas. At this time Philae was inundated for part of each year, from December to August. When it did emerge from the waters of the Nile, it appeared sorrowfully shorn of its vegetation. The picturesque ruins rose from black silt-laden soil with not a shrub nor tendril to break their barren appearance.

Between 1929-34 the Aswan Dam was raised another ten metres, to a height of 44.5 metres. Philae was now inundated for most of the year. Only the high pylon of the temple of Isis, and the kiosk of Trajan, situated at its highest point, could be seen. Small boats could, with difficulty, sail beneath the great architraves. The capitals of the Tolty columns alone hinted at what architectural treasures lay beneath the water. Being constructed of sandstone, submersion caused no lasting damage. In fact, the monuments strengthened from contact with water. And the silt which packed against the reliefs, though stripping them of colour, actually protected them.

The decision to build the High Dam (Saad El Aali) in 1960 caused attention to be focused once again on the fate of Philae. For now, with the constant high level of the water, the monuments would be totally inaccessible. Moreover, the swirling currents from the High Dam that was built south of the island and the existing Aswan Dam to the north would cause them irreparable harm, if not bring about their total collapse.

Egypt launched an international appeal through UNESCO. Philae was brought into the limelight. Projects for saving the monuments were many and varied. All were studied. One project was to build a protective dam on the west, cutting off the island from the main flow of the river and, theoretically, letting it rest in a lowerlevel lake of its own. This project was abandoned on the grounds that constant pumping out of water would be required to keep the lake at a constant level. The final decision was to dismantle the monuments and re-erect them on another island: Agilkai, slightly to the north of Philae.

An Italian contracting company was chosen to carry out the work. They started with the construction of a coffer dam in 1977. The water was then pumped out, and when the greyish-green blocks were exposed they were dissected, stone by precious stone (fortyseven thousand in number), cleaned, treated, marked and stored.

During the dismantling operations, many blocks of earlier monuments were found to have been reused, especially in the foundations of the buildings. For example, a kiosk dating from the 26th Dynasty during the reign of the pharaoh Psamtik II (594-588 BC) was found dismantled and reused on the western part of the island. Beneath the flagstones of the hypostyle hall of the temple of Isis, another temple, also dating from the 26th Dynasty, was brought to light. Nektanebos, the first ruler of the last, zoth Dynasty (387-361 BC) had reused granite and sandstone blocks inscribed with the names of Amenhotep II, III and Thutmose III for his own constructions on the island, but these had come from temples elsewhere since Herodotus made no mention of Philae when he visited Aswan in the mid-filth century BC.

While dismantling operations continued, the Egyptian High Dam Company blasted 450,000 cubic metres of granite off the top of Agilkai island. They used some of this to enlarge part of the island to resemble the shape of Philae in order to contain the monuments without distortion. The stones from the dismembered temples were then transported to their new home, and, in a record of thirty months, have been re-erected in an even more perfect condition than before, for many of the reused or fallen blocks that were located were used to reconstruct the original temples.

In March 1980, following an impressive public inaugural ceremony, Philae was declared open to the public. Visitors may once again view the elegant colonnades, the celebrated kiosk and the magnificent Temple of Isis. Soon, when plants take root, the ‘Pearl will once again fit the description of Amelia Edwards who wrote in 1873/74: ”Seen from the level of a small boat, the island, with its palms, its colonnades, its pylons, seems to rise out of the river like a mirage. Piled rocks frame it on either side, and purple mountains close up the distance. As the boat glides nearer between glistening boulders, those sculptured tomers rise higher and ever higher against the sky. They show no sign of ruin or of age. All looks solid, stately, perfect.*

DESCRIPTION OF MONUMENTS

The monuments of Philae cover four major epochs: the last part of the Pharaonic era, the Ptolemaic period, the Roman epoch and the Christian period. The chief monuments are the Temple of Isis (1) and her son Horus (Harendotus) (2), the beautiful Arch of Hadrian (3), the Temple of Hathor (4) and the Kiosk (5), which is also known as Pharaoh’s Bed.

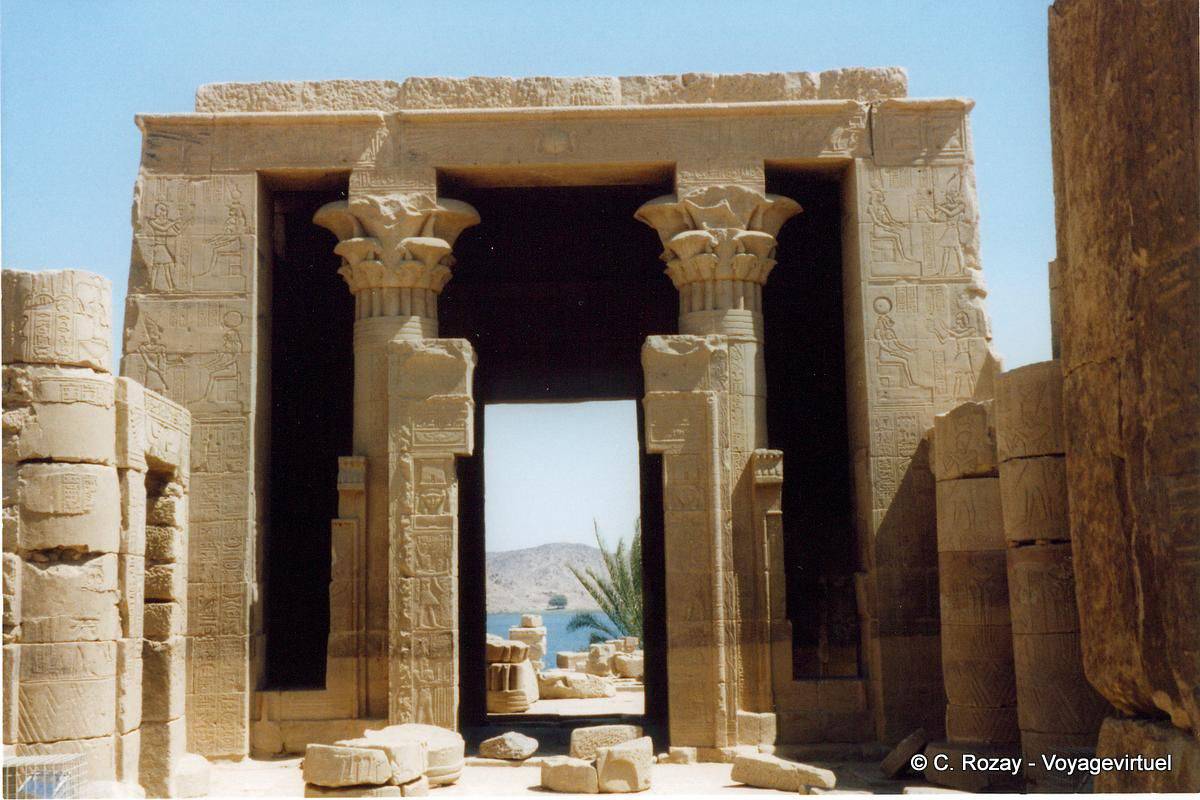

The Entrance to the island (a) was originally constructed by Nektanebos, the first ruler of the last Dynasty; it was designed with fourteen columns and two sandstone obelisks on the river front. Unfortunately, a particularly high flood swept the structure away soon after it was completed, and it lay in ruin until Ptolemy II had it restored; some of the columns were reconstructed. These have double capitals; the lower parts are decorated with different floral forms and the upper bear heads of Hathor. The screen walls between the columns, crowned with concave cornices bearing rows of uraeus serpents, show Nektanebos making offerings to the deities.

We now stand on the threshold of Philae. Before us a great Outer Court (b) opens up. This leads to the Temple of Isis about one hundred metres ahead. The court is flanked by colonnades. On the right only half a dozen of the planned sixteen columns were completed; also to the right are the temples of Arhesnofer (d), Mandolis (e) and Imhotep (f).

To the left, the thirty-two columns of the colonnade follow the shore line. No two capitals are alike. The shafts show Tiberius making offerings to the Egyptian gods. The ceiling is decorated with stars and flying vultures. The representations are all finely executed and mostly well preserved. For example, between the first two columns (c), above the window, Nero is depicted offering two eyes to Horus, Isis and “The Lord of the Two Lands’.

The Isis Temple Complex

The huge Entrance Pylon (P. 1) lies ahead. It is eighteen metres high and forty-five metres wide. Each of the two towers is decorated with mighty figures of Neos Dionysos, Ptolemy XII, depicted as pharaoh and wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. He clasps enemies by the hair and raises his club above their heads to smite them in the presence of Egypt’s best loved deities: Isis and Nephthys, Horus and Hathor. Thus did the Ptolemaic kings give themselves credit for suppressing Egypt’s traditional enemies and honouring local traditions.

Two granite lions guard the entrance; they are of late Roman times and reflect Byzantine influence. On the lintel of the gateway between the two towers of the pylon is a representation of the pharaoh Nektanebos I in a dancing attitude in front of Osiris, Isis, Khnum and Hathor. Much of the dignity and austerity of the divine pharaoh as the powerful and unapproachable ‘Son of the Sun-god’, was lost during the Late Period, when representations tended to show informal attitudes.

Passing through the gateway, we come to the Great Court (g). To the right is a colonnade and priests’ quarters. To the left is the Birth House (which may also be approached from a doorway at the centre of the left-hand tower of the entrance pylon.

The Birth House is an elegant little building. The entrance portico has a roof supported by four columns and is followed by three chambers, one behind the other. Around three sides of the building runs a colonnade with floral capitals surmounted with sistrum capitals and Hathor heads. The reliefs throughout the building relate to the birth of Horus, son of Isis, and his growth to manhood to avenge his father’s death. All are in a fine state of preservation.

The first chamber is not decorated. In the second some quaint protective deities are depicted among the papyrus plants where Horus was born. In the third chamber is a scene (on the rear wall near the bottom) showing Isis giving birth to her son in the marshes of the Delta. With her are Amon-Ra and Thoth. Behind Amon-Ra is the serpent goddess of Lower Egypt and the god of wisdom’. Behind Thoth is the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt and the god of ‘reason’. Above this scene Horus, as a hawk, stands among the papyrus plants crowned with the Double Crown.

On the left-hand wall the standing child Horus suckles at the breast of Isis. Ptolemy IX (Euergetes II) hands two mirrors to Hathor, who places her hands in blessing on the head of the child.

The colonnade surrounding the Birth House is completely decorated. The scene at the beginning of the right-hand colonnade shows the youthful Horus, nude, but wearing the Double Crown. He is with his mother Isis before the serpent goddess of Buto, who plays the harp to them. Augustus stands behind the serpent goddess carrying a vase. The relief of a cow in the marshes that is depicted above the vase indicates the ornamentation within it.

Returning to the Great Court (g) we approach the Second Pylon (P. 2) which is smaller in size than the entrance pylon and is not aligned with it. To the right (1) is a large granite block inscribed by the Kushite pharaoh Taharka (730 BC), which is therefore the earliest piece of work on the island. Constructed into the base of the right-hand tower, is a large rock. It is inscribed with the text about the tithe on fishermen. Beyond lies the Isis temple proper.

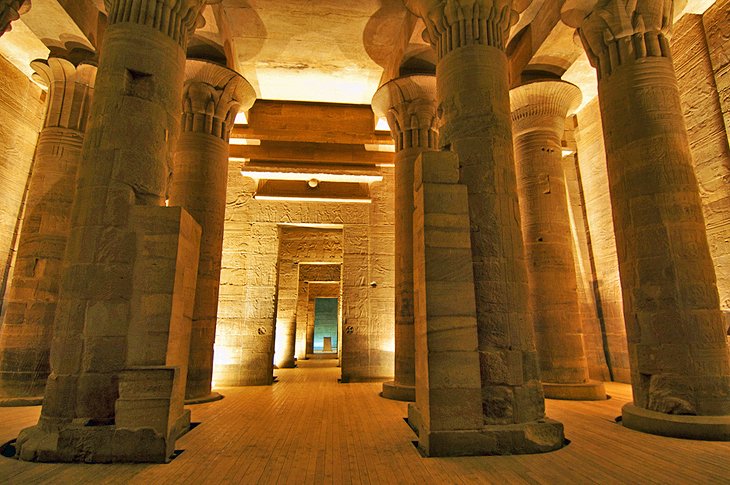

The Temple of Isis comprises a tiny open court (), a hypostyle hall (k), an ante-chamber (1) and a sanctuary (m). The walls have fine reliefs of the Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors repeating traditional, and by now familiar – if not somewhat wearisome ritual scenes relating to offerings to the Egyptian gods, staking out the temple and consecrating the sacred area.

The Hypostyle Hall (k), which is separated from the court by screen walls between the first row of columns, is adorned with coloured relief from the lower to the upper reaches of the wall, across the ceiling, and from shaft to capital. The columns and capitals provide a good example of the style, decoration and colouring of the Graeco-Roman period, when less regard was paid to natural colours. For example, the blue ribs of the palms stand out somewhat garishly from the light-green palm twigs on the capitals of the columns.

This hall was converted into a church in the Christian Period, when the wall reliefs were covered with stucco and painted. Christian crosses were chiselled in the walls and on some of the columns. In Act, 1Greek inscription on the right-hand side of the doorway leading to the ante-chamber (1) records the ‘good work of destruction of pagan reliefs!) carried out by the Bishop Theodorus in the reign of Justinian, in the fifth century AD.

The sanctuary (m) has two tiny windows and a pedestal on which the sacred barge bearing the statue of Lsis stood. This pedestal was installed by Ptolemy III (Euergetes 1) and his wife Berenice. Surrounding the sanctuary are the usual priestly chambers and storerooms.

Above the sanctuary are the Osiris Chambers, which are approached from a stairway to the left of the temple (n) but currently closed to visitors. In these chambers interesting reliefs relate to the death of Osiris and his rebirth. Among the scenes are: Osiris among the reeds where his body came to rest; the body lying on a bier being prayed over by the jackal-headed Anubis along with Isis and her sister Nephthys; Isis and Nephthys spreading their wings beside the bier as Osiris regains his powers. It is to such graphic portrayals of ancient Egyptian traditions by the Ptolemies that we owe much of our interpretation of ancient Egyptian mythology.

To the left of the stairway (n) is a doorway leading out of the Temple of Isis. A road leads to the temple of Horus (Harendotus), son of Isis (2), and Hadrian’s Gateway (3). The latter contains the famous relief relating to the source of the Nile on the right-hand wall, in the second row from the top. It shows blocks of stone heaped one upon the other, and standing on the top is a vulture (representing Upper Egypt) and a hawk (representing Lower Egypt), beneath the rocks is a circular chamber which is outlined by the contours of a serpent, within which Hapi, the Nile-god, crouches. He clasps a vessel in each hand, ready, at the appointed time, to pour the water from the ‘eternal ocean’ to earth in his urns.

The Temple of Hathor

To the right of the temple of Isis, is a large, circular castor-oil presser. The oil was used for medicinal purposes. The Temple of Hathor (4) has lively and charming representations, as befitted the goddess of love and joy. The columns are decorated with fluteplayers and with representations of the laughing dwarf-deity Bes, playing a tambourine and a harp. Apes play the lyre, priests carry an antelope, and Bes dances.

Elsewhere in Egypt, the early Christians were escaping from Roman persecution. They were abandoning their worldly possessions and fleeing to the desert. But here, on the island of Philae, a spirit of light-hearted joy prevailed.

The Kiosk (Pharaoh’s Bed)

The Kiosk of Trajan (5) is rectangular in shape and surrounded by fourteen columns with floral capitals. These support blocks that carry the architraves and cornice. The blocks were undoubtedly planned to be carved into sistrum capitals, but they were left unfinished, as were other parts of the structure. The emperor Trajan (AD 98-117) is depicted burning incense in front of Osiris and Isis and offering wine to Isis and Horus. This is possibly the most graceful of the many elegant buildings on the island, and the one for which Philae is most remembered.

MEDIAEVAL TRADITION

Christianity finally came to the island of Philae and, after the Arab conquest, many of its inhabitants embraced Islam. There being no further need for isolation from the mainland, the population gradually dwindled. By the Middle Ages the island was deserted. It was then that there developed a tale that is strongly reminiscent of the myth of Isis, searching for her loved one Osiris.

It was said that a certain Zahr el-Ward, Rose Blossom’, beautiful daughter of a grand vizier, fell in love with a young man called Anas el-Wogud. The youth was not accepted by the girl’s father who, to protect his daughter, shut her up in the temple of Isis on Philae and told her lover she had gone away.

Anas was not content with the explanation and searched the country for her. Through the Delta and Upper Egypt he went, searching everywhere, until he finally found her on the island. Unfortunately he could not cross the river which was filled with crocodiles, and it was only because he was known throughout the land for his kind and tender heart, and his love of all creatures, that one of the crocodiles allowed him to climb on its back and swim across the river with him.

Meanwhile the beautiful Zahr el-Ward had been planning her vescape. Not knowing that her lover knew her whereabouts, she managed to slip out of the temple and find a boat. It is fortunate that the crocodile bearing the lover and the boat bearing the girl met in midstream, where they were reunited much as Horus and Hathor were annually reunited in the ‘Good Union’.

When the father realised that he could not come between the lovers, he allowed the wedding to take place in the Osiris Room on the roof of the sanctuary of the temple of Isis.

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!