Cochasquí: The Immense Pyramids of Ecuador Provide Evidence for a Forgotten Civilization

The archaeological sites in Ecuador are often overshadowed by more popular locations in neighboring Colombia and Peru. However, archaeology enthusiasts have a wealth of options including more than just well-known Ingapirca to admire. Take for example the huge, 83.9-hectare site of Cochasqui, where pyramids and sacred animals patiently remind us that Ecuadorian archaeology holds more secrets than most people recognize. The debate is on: was Cochasquí a home for Quitu Cara elite, an astronomical observatory, a fortress, a sanctuary, or did it serve some combination of functions?

Architecture and Archaeology of the Site

There are 15 flat-topped pyramids constructed at Cochasquí. Nine of them have ramps. 21 large, circular funerary mounds have also been noted. This is not a small site!

Model of the Cochasquí archaeological site, showing funerary mounds and flat-topped pyramids. (Alicia McDermott)

The pyramids were created with cangagua (a volcanic rock-like material). Scholar say the 160kg (352.74 lbs.) cut blocks of rock were softened with water and then cut using harder volcanic rock tools (the site was inhabited before the Iron Age).

Most of the pyramids are left overgrown to protect the environmentally sensitive cangagua blocks. However, the largest pyramid, pyramid 9, has a wide gap in the middle where previous landowners of the site sent a channel of water through in search of treasure.

- The Inca-Caranqui Water Temple of Ecuador: A display of wealth and skillful hydraulic engineering

- Subway Station or Cultural Preservation? Development Clashes with Patrimony at a World Heritage Site

- Pucara de Rumicucho Is More than just an Incan Stone Fortress

Canagugua blocks (top) and the partially destroyed pyramid 9 (bottom). (Alicia McDermott)

The Cochasquí archaeological site is 3100 meters (10170 ft.) above sea level and extremely close to the equator. It has an unrivalled view of 280 degrees, including views of a combination of snow capped mountains and volcanoes. Archaeological investigations have taken place on and off since 1932. The most well-known archaeologist to study the site was the German Max Uhle.

The ceramic artifacts found at Cochasquí have enabled archaeologists to split the occupation of the site into two periods. Cochasquí I ran from 950-1250 AD and the zapato (shoe) style of thicker ceramic was popular. In Cochasquí II, from 1250-1550 AD, people had elaborated on their ceramic designs, included paint, handles, and were making thinner and finer ceramics. The popular style of this time period was the tripod, which some say is a reflection on the family – with one leg as a symbol of the mother, another as the father, and the third as their child.

Tripod ceramics which were discovered at the site. (Alicia McDermott)

Artifacts coming from Colombia, the coastal region of modern day Ecuador, and the Amazon region all have been found at Cochasquí. This shows that the community living at the site had contact with far away cultures and likely participated in trade and cultural interaction with them. Instruments such as a llama bone flute and countless jars, bowls, and statues, as well as stone artifacts, have all been uncovered.

A statue, llama bone flute, stone tools, and one of the many ceramics found at Cochasquí. (Alicia McDermott)

Quitu Cara burial styles have been brought to light at this site as well. It was common practice for people to be buried sitting in jars. In one of the on-site museums you can see a burial of a 1.5-1.6 meter (4.9-5.2 ft.) tall woman who was buried with necklaces and bracelets similar to the style still worn by indigenous women in the area today.

The skeleton of a woman who was buried at Cochasquí. (Alicia McDermott)

It is also said that, when archaeological excavations were underway at the largest pyramid, guides at the site claim over 700 skulls were unearthed. This has led some scholars to suggest that the huge pyramid was the location of human sacrifices.

More recent geo-radar studies suggest that there may have been people living at the site before the Quitu Cara as well. However, this information is being kept mostly in closed quarters until more details can be provided.

Reconstruction of the llama skin clothing which may have been worn by a previous inhabitant of Cochasquí. (Alicia McDermott)

Who Lived at Cochasquí?

Their geographical position means the people living at what is now called Cochasquí could have been well-prepared for any attacks. However, guides at the site claim that the people living at Cochasquí were farmers, not fighters. Simple hammers, stone hatchets, arrows and rocks tied on string were used to protect their homes. However, there is also a popular local pride that Quitu Cara warriors were able to withstand Inca conquerors until Huayna Cápac had his day at Yaguarcocha.

Replicas of some of the weapons. (Alicia McDermott)

Although official excavations have not been carried out further down the hill, it has been suggested that there was probably a settlement close by. If anyone lived on the hill alongside, or on top of, the pyramids, it could have been shamans or other elite members of the Quitu-Cara society. Some archaeologists claim no one lived on the pyramids and they may have been the bases for temples to the sun and moon or a sanctuary.

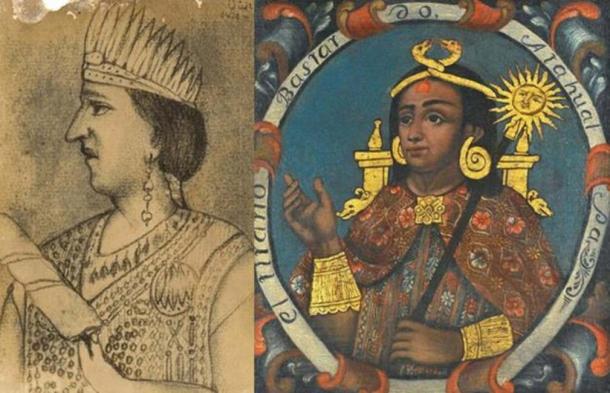

The ruler who is said to have built the site was a woman named Quilago (Quelago). It is believed that the society at Cochasquí was matriarchal. Cochasquí was a major site for the Quitu Cara and the famed Inca Atahualpa was the son of either Quilago or a Quitu princess named Paccha Duchicela, who it is also said had lived at Cochasquí. This would have cemented bonds between the Quitu Cara and the Inca civilizations and may have been a method to prevent fighting with the more warlike Inca people.

Paccha Duchicela XVI (Public Domain) and Atahualpa. Brooklyn Museum. (Public Domain)

Today, when you visit the site you will probably come across llamas, alpacas, and the llama-alpaca hybrid called a guariso during your trek. The llamas hold particular interest as they were believed to be sacred fertility animals by the Andean ancestors. These camelids were primarily used in the past as sources of food and clothing. Llama bones and skin were also turned into musical instruments by the early inhabitants of Cochasquí. A final interesting note about the llamas – pyramid 14 is dubbed the pyramid of fertility because that is where the llamas are said to prefer to mate. Apparently, there is also a belief that pyramid 14 can help human couples in their fertility as well. Several marriages have taken place at pyramid 14.

Llamas, alpacas, and guarisos are today protected species at the archaeological site. (Alicia McDermott)

Quitu-Cara: A Forgotten Kingdom?

It would be better to go into more detail in another article on this topic, but it is worthwhile to mention here the ongoing debate whether the Quitu-Cara (Kitu Kara) civilization was large enough to be called a real Pre-Inca kingdom. Apart from the strong indications present at Cochasqui, several other archaeological sites have been found from the coastal to Amazon region stretching from the north of the Pichincha province to the southern realms of Colombia, all suggest that yes, the Quitu-Cara had sufficient social, technological, and scientific organization to be called one complete civilization and perhaps even a kingdom.

- Lake of Blood: The dark history of Laguna Yahuarcocha, Ecuador

- New Expedition Hints at a Lost City Near the Tayos Caves in Ecuador

- Earthquake in Ecuador Reveals Bizarre Burial of a Mummy in a Jar with a Little Mouse

Astronomical Awareness

Although there is some controversy surrounding the idea, many people say pyramid 5 is built following the shape of the Scorpio constellation. Another pyramid is said to follow the form of the Southern Cross. There are also tombs at Cochasquí which provide a terrestrial mirror of the constellation Ursa Major.

The sun and moon were both considered important to the agricultural society atop the hill. The sun would give life to their crops and the moon was helpful in deciding when to plant, harvest, and practice other agricultural activities. There are two baked clay platforms at the site. One is said to act as a lunar calendar of 13 months – in sync with the feminine cycle and prehistoric agricultural cycle. There are holes in the platform where cones could have been added to mark the passage of time throughout the year and the time to change an agricultural activity. Two small canals may have also been filled with water to reflect the lunar phases.

Photos of the moon platform (above) and the sun platform (middle), with a drawing of both (below). (Alicia McDermott) The moon platform is the smaller platform.

A larger platform located nearby has been linked to the sun. Sun worshipping activities may have taken place at this location as well as other social events. This platform seems to be split into four, possibly corresponding with the solstices and equinoxes.

Top Image: Part of the Cochasquí archaeological site. (Santiago Martinez/ L. Ortiz) A mask found at the site. (Alicia McDermott)

By Alicia McDermott

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!