Lighting Up Saqqara: An Electrifying Theory for the Serapeum Sarcophagi

The Serapeum of Saqqara has been a continuous source of speculation and mystery since its re-discovery in 1850. Even now, no theory has been able to explain exactly how or why the 24 giant sarcophagi were moved to the site and precisely installed in their notches. The mainstream theory suggests the site was used for the burial of Apis bulls, though there are many elements which do not add up with this belief.

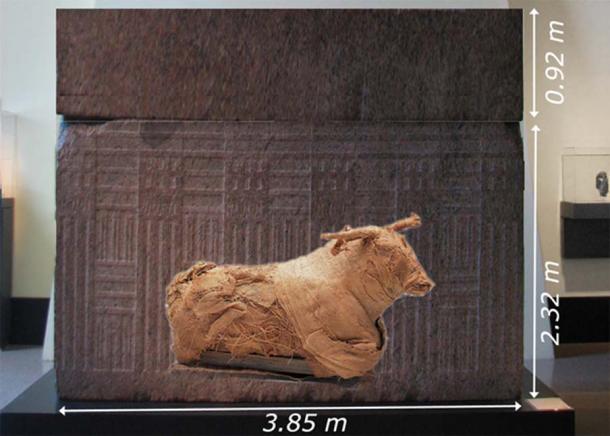

For example, the size of the boxes exceeds the size of the bulls; was it done to provide extra comfort for them? Why not do the same for the pharaohs, who were buried in tiny coffins barely fitting their bodies? Why did they make the Serapeum sarcophagi out of granite and not with limestone, a material much easier to work with? And if Serapeum was the burial site for the Apis bulls, where are the bull mummies?

A little Photoshop to compare the size of a bull (which is about 2.3 meters long) and a Serapeum sarcophagus based on measurement by Linant-Bey. This is a typical bull mummy from Dynastic times. (soul-guidance.com)

Several people reject the theory of the Serapeum having been used for ceremonial burials (at least not in the grand gallery of the site where the large coffins are located), but if not that, then what was it used for? That is the question posed by some Egyptologists…and it is little wonder that they hear a “sound of crickets chirping” in return – in other words, they’ve found no other plausible alternative theory. By default we fall back to the Apis theory with all its flaws. I gave this some thought and put together a theory which seems to answer some of the questions. Here are my insights.

- The Evidence is Cut in Stone: A Compelling Argument for Lost High Technology in Ancient Egypt

- The Lost Knowledge of the Ancients: Were Humans the First? Part 1

- The Qurna Eviction: Separating the Living from the Dead in Egypt

Fermentation in Pre-Dynastic Egypt

It is well known that pre-dynastic Egyptians knew the process of fermentation. By about 3000 BC they had already utilized the process to brew beer and bake bread. And some scholars have said the process was known even before then. Let’s assume someone in pre-dynastic Egypt mixed some starch and meat, placed those ingredients inside a giant coffin, and closed the lid. A particular set of ingredients come in mind: bread, beer, barley and oxen, as those are mentioned so many times in ancient Egyptian texts. As fermentation starts, yeast begins to convert the starch present in barley into CO2 gas and ethanol. The amount of the CO2 gas increases in the box, building pressure. I will explain later why this pressure is important, but first let’s analyze this setup.

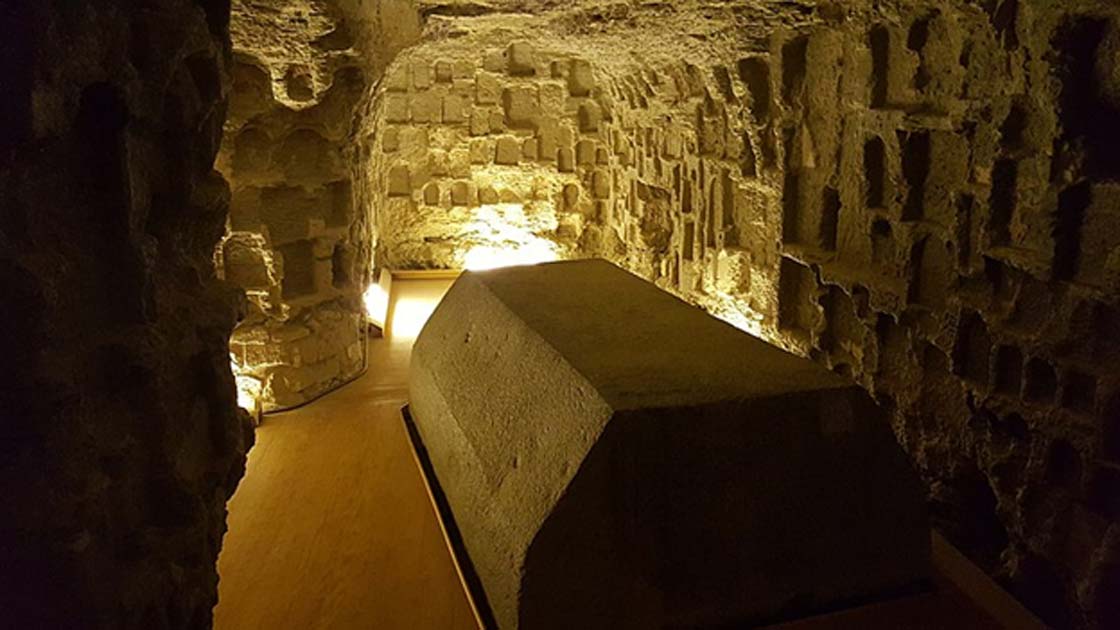

One of the sarcophagi in the Serapeum, Saqqara, Egypt. (Sailingstone /Adobe Stock)

The granite boxes are made with high precision and have a tolerance within 1 micron. So, closing the lid essentially makes them hermetically sealed. Granite is not a porous material, so little of the gas would seep through the walls. The lid also weighs about 30 tons, so the pressure of the gas would have to be substantial before it would pop open. The process continues as long as the chemical composition of the substances inside the sarcophagus and the temperature are comfortable for yeast to keep growing.

One of the Serapeum sarcophagi in Saqqara, Egypt. (Ovedc/CC BY SA 4.0)

One component essential for yeast to grow is oleic acid. This is a fatty acid present in animal and plant fat. Oleic acid is essential for the yeast to maintain its growth rate. This acid is also essential for yeast to overcome the toxic effect of ethanol, which would be building up in the coffin as a byproduct of fermentation. That acid is present in abundance in meat. I cannot help but wonder if the main purpose of the meat or bull body parts placed in the huge granite boxes was to provide proper chemical components for the yeast to sustain long term growth.

As fermentation continues, the CO2 gas builds pressure in the granite box. The granite can withstand at least 200 MPa pressure. To put this in perspective, this is as much as 1000 times more pressure than car tires have. The yeast in the box would be exposed to that pressure – and it is capable of withstanding that much stress. As pressure grows, there will be mechanical stress on the huge granite box. It is well known granite is made of quartz crystals and under mechanical stress those crystals generate electric charge. Thus, more pressure means more electric charge is generated.

Example of granite rock in the cliff of Gros la Tête – Aride Island, Seychelles. The thin brighter layers are quartz veins, formed during the late stages of crystallization of granitic magmas. They are also sometimes called “hydrothermal veins”. (Etan J. Tal/CC BY SA 4.0)

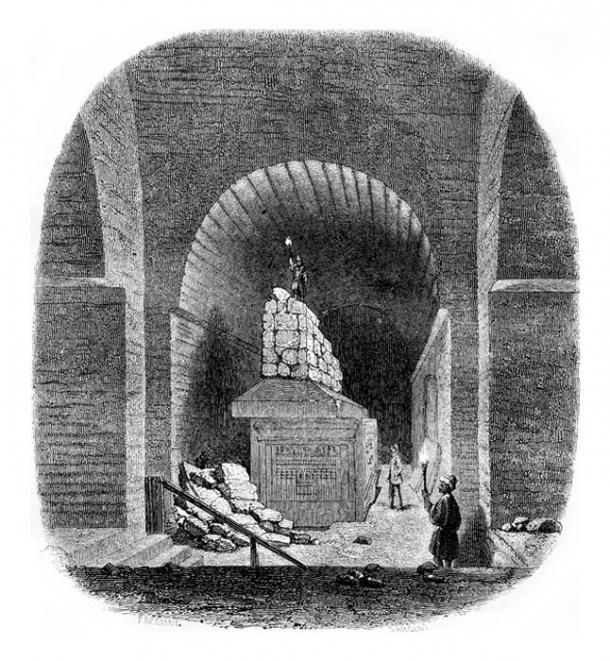

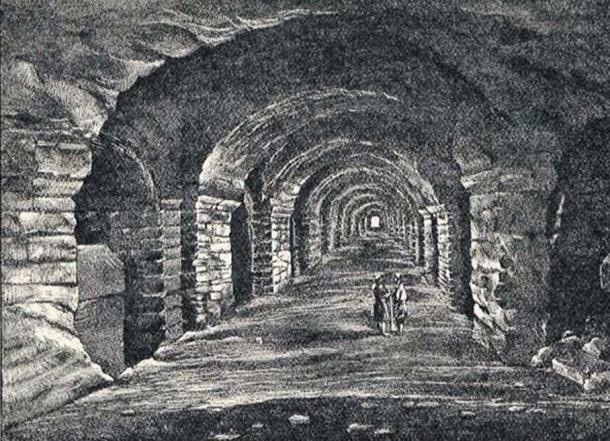

At some point, the pressure inside the box will overcome the lid weight and pop it open, releasing the gas. However, when the Serapeum was rediscovered in 1850, a few sketches were made of the interior at that time or shortly after. The following image is one of those sketches. One interesting aspect that cannot be missed in this picture is the stack of stones piled on top of the sarcophagus’ lid. It appears someone may have used blocks to counter the pressure inside the box with additional weight mounted on the lid, essentially extending the pressure of the quartz crystals.

One other point to make here is that if someone opened the lid of the Serapeum sarcophagi millennia later, most likely that person would see only what the yeast did not consume before drying out. That would be bull bones, which is exactly what Mariette found in the Serapeum when it was discovered in 1850.

Serapeum of Saqqara. Le Serapeum de Memphis, Vue interieure. Illustration for Le Magasin Pittoresque (1855). (Morphart / Adobe Stock)

Giant Sarcophagi or Giant Batteries?

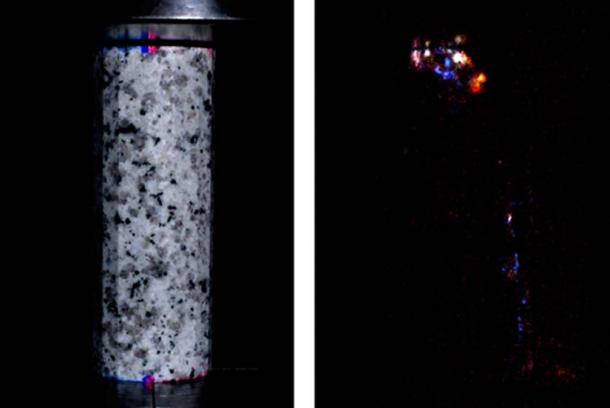

Many who have visited the Serapeum since it was opened may have noticed that no soot is present on the ceiling and the walls. Upon making note of this, one cannot help but wonder how all the work was completed underground in complete darkness. Giving this some thought, I do not think the place would have been dark at all. The effect of high pressure stress on granite material and luminescence caused by that stress was analyzed by Kato, Mitsui, and Yanagidani in 2010.

In the study, a slab of granite was selected and stressed with high pressure to the point that light began to glow on the stone’s surface. The image below shows the experimental results from that study. As analyzed in the paper, granite under stress builds voltage potential on its surface. If the voltage is high enough, it ionizes the air around the surface, creating a glow.

Granite glow under high pressure. (Author provided)

As the pressure built in the granite boxes of the Serapeum, I do not think the grand gallery would have been dark. However, it is very unlikely that builders went to the effort of moving so much weight around just to light the hall of the grand gallery. There has to be a more pragmatic reason. Let’s consider how the electric charges could have been utilized in ancient Egypt.

Sketch of the Serapeum’s grand gallery and view of the grand gallery today. (soul-guidance.com)

Earthquake Lights

Over the centuries, there have been numerous reports of lights which appear in different shapes, forms, and for different lengths of time above the ground surface shortly before, during, or after earthquakes. One recent instance of an earthquake light occurrence was reported in L’Aquilla, Italy in 2009, when the place was hit with a 6.3 tremor. Shortly before the earthquake, people reported seeing lights above the city. The phenomenon was analyzed in detail and about 1000 people were interviewed. The conclusion of the study was that the electric charges released during the earthquake caused the light effect.

- 4,000-Year-Old Relief Carvings and Decorated Stone Blocks Discovered in Temple of Serapis in Egypt

- Boats, Bowling and Moldy Bread: Curious Achievements Ancient Egypt Shared With the World

- Common Tools or Ancient Advanced Technology? How Did the Egyptians Bore Through Granite?

Even though the phenomenon is known since antiquity, recent video monitoring (pretty much installed on every corner in cities) helps researchers analyze it. And a few research teams have done so. A team at San Jose University lead by Professor Freund compiled data from 65 different sites around the world where earthquake lights were noticed. Extensive work has been done on analyzing the data and the physics behind it. Results show the earthquake light phenomenon is caused by stress in granite material present in soil. Theoretical and experimental verification has been completed to support the results.

I can only wonder if the same mechanism for light implementation could have been used in the Serapeum in Pre-Dynastic times. If you think about it, all of the necessary components were present at the site. As the granite boxes experienced mechanical stress electric charges would appear. The charges typically are dispersed toward the ground surface. When the charges reach the surface, they ionize air pockets above the ground and would have lit the sky above Saqqara.

In summary, I think the giant Serapeum sarcophagi were used to generate electric charges with pressure built inside by CO2 gas. The pressure put on the quartz crystals created electric charges on the surface of the sarcophagi. Those charges were then dispersed from underground toward the ground surface. The released charges would have ionized the air above Saqqara, causing the air to glow.

A sarcophagus in the Serapeum, Saqqara, Egypt. (Sailingstone /Adobe Stock)

Top Image: One of the Serapeum sarcophagi in Saqqara, Egypt. Source: Ovedc/CC BY SA 4.0

By Konstantin Borisov

Updated on January 27, 2022.

References:

Margarett R. Bunson. 2002. “Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt” ISBN: 0-8160-4563-1. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data.

Mohamad Ibrahim and David Rohl. 1988. “Apis and the Serapeum” Journal of ancient chronology forum. Vol 2

Antoine Gigal ”From beyond the secrets of Serapeum” Archeological and historical researches http://www.gigalresearch.com/uk/publications-serapeum.php

Auguste Mariette-Pacha, Gasto Maspero. 2010. ”Le Serapeum de Memphis” Kessinger Publishing, LLC, ISBN-10: 1166740765

Ian Spencer Hornsey. 2003. “A history of beer and brewing”. Published by royal society of chemistry, ISBN: 0-85404-630-5

Alice Stevenson. 2016. “ The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation” Journal Archeological Research, Dec, Vol. 24, issue 4, pp 421-468 (beer and bread making).

J. Allen. 2015. “the Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts (Writing from the ancient World)”, SBL Press; Second edition, ISBN10: 1628371145

Chris Dunn. 2010. “Lost technologies of Ancient Egypt: Advanced Engineering in the temples of the pharaohs” ISNB-10: 1591431026

M. Schild S. Siegesmund A. Vollbrecht M. Mazurek. 2001. “Characterization of granite matrix porosity and pore-space geometry by in situ and laboratory methods” Geophysical Journal International, Volume 146, Issue 1, July, Pages 111–125.

Ronald W. Walenga and William E.M. Lands. 1965. “Effectiveness of Various Unsaturated Fatty acids in supporting Growth and respiration in saccharomyces cerevisiae” Journal of Biological Chemistry Vol. 250, No. 23, Issue of December 10, pp. 921-9129

Kyung Man You, Claire-Lise Rosenfield and Douglas C. Knipple. 2003. “Ethanol Tolerance in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is dependent on cellular oleic acid content” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, March, vol.69, no. 3, 1499-1503

Felix H. Lam, Adel Ghaderi, Gerald R. Fink, Gregory Stephanopoulos. 2018. “Engineering alcohol tolerance in yeast” American association for the advancement of science (AAAS)

P.M.B Fernandez. 2005. “How does yeast respond to pressure?” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, August, Volume 38(8) 1239-1245

Mamoru Kato, Yuta Mitsui, Takashi Yanagidani. 2010. “Photographic evidence of luminescence during faulting in granite” Earth, planet and space, May, Volume 62, Issue 5, pp489-493

I.V. Florinsky. 2016. “Earthquake Lights in Legends of the Greek orthodoxy” Mediterranean archaeology and archaeometry, Vol. 16, No 1, pp. 159-168

C. Fidani. 2010. “The earthquake lights (EQL) of the 6 April 2009 Aquila earthquake, in Central Italy” Natural Hazards and Earth system sciences, May.

Friedemann T. Freund, Akihiro Takeuchi, and Bobby W.S. Lau. 2006. “Electric currents streaming out of stressed igneous rocks- A step towards understanding pre-earthquake low frequency EM emissions” Physics and chemistry of the earth

Brian Clark Howard. 2014. “Bizarre Earthquake Lights finally explained” National Geographic

Friedemann T. Freund. 2003. “Rocks that crackle and sparkle and glow. Strange pre-Earthquake phenomena” Journal of Scientific exploration. Vol.17, no. 1, pp 37-71

Robert Theriault, France St-Laurent, Friedemann T. Freund, and John S. Derr “ Prevalence of Earthquake lights associated with rift environments” Seismological Research Letters, Vol. 85, Number 1, Jan/Feb 2014.

Freund, F. 2007. “Pre-earthquake signals – Part I: Deviatoric stresses turn rocks into a source of electric currents”, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 7, 535–541.

Scoville, J., et al. 2015. “Pre-earthquake magnetic pulses” Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 15, 1873-1880, doi:10.5194/nhess-15-1873-2015

Bishop, J. R. 1981. Piezoelectric effects in quartz-rich rocks. Tectonophysics, 77, 297–321

Derr, J. S. 1973. Earthquake lights: A review of observations and present theories. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 63, 21277–21287.

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!