Ever since Johan David Åkerblad’s time, researchers have assumed that Swedish Vikings must have been behind the tagging found on both sides of the lion.

At the very turn of the 18th century, the 36-year-old Swedish diplomat and linguist Johan David Åkerblad visited Venice. One day he was out walking, looking at famous objects and sites in this Italian city in the heart of the Adriatic Sea.

He suddenly noticed something.

On both sides of the large lion outside of Arsenal, Venice’s old naval base, someone had inscribed what the knowledgeable Åkerblad was immediately able to recognize as Scandinavian runes.

Did Vikings really go to Venice to tag ancient art treasures?

They didn’t, even though the city had already existed in their time.

The explanation is that the lion had been located in a completely different place before it came to Venice: the Athens port city of Piraeus.

Norwegian Vikings

Ever since Johan David Åkerblad’s time, researchers have assumed that Swedish Vikings must have been behind the tagging found on both sides of the lion.

There has been good reason for that, since the runes on the left side of the lion actually tell of “svear” (swedes) and the runic loop here is very similar to what can be seen carved into runestones in several places in central Sweden.

The Icelandic-Swedish rune researcher Thorgunn Snædal investigated the Piraeus Lion a few years ago more thoroughly than any previous researchers have done.

Her study mentions several things that suggest that Norwegian Vikings may have drawn the beautiful loop with runes on the lion’s right side. This is the one that is visible in the picture at the top of this article.

The runes on the three-metre high Piraeus lion were carved at a time when famous Norwegian Mediterranean explorers such as Harald Hardrada and Sigurd Jorsalfare were alive.

Snorri has written about Sigurd Jorsalfare, who rode in through the ‘Golden Gate’ (city gate) when he was stopped in Miklagard (Constantinople) on his journey to Jerusalem in 1108‒1111. This illustration by Gerhard Munthe from 1899 was made for Snorre’s book ‘Heimskringla’.

Used the lion for shooting practice

In the middle of the 19th century, Carl Christian Rafn, secretary of the Royal Nordic Society of Antiquaries, was responsible for the translation of the ‘Norwegian’ runes on the lion’s left side as describe above. However, the translation is uncertain, as many of the runes can no longer be read.

The names Åsmund, Asgeir (Eskil) and Torleif are still legible.

The runic inscriptions on the Piraeus Lion in Venice are about to disappear. Air pollution, in combination with weather and wind, are contributing to their slow disappearance.

But Turkish, or perhaps Venetian, soldiers did more damage when they used the lion for target practice almost 350 years ago. You can clearly see the bullet holes in the pictures of the lion.

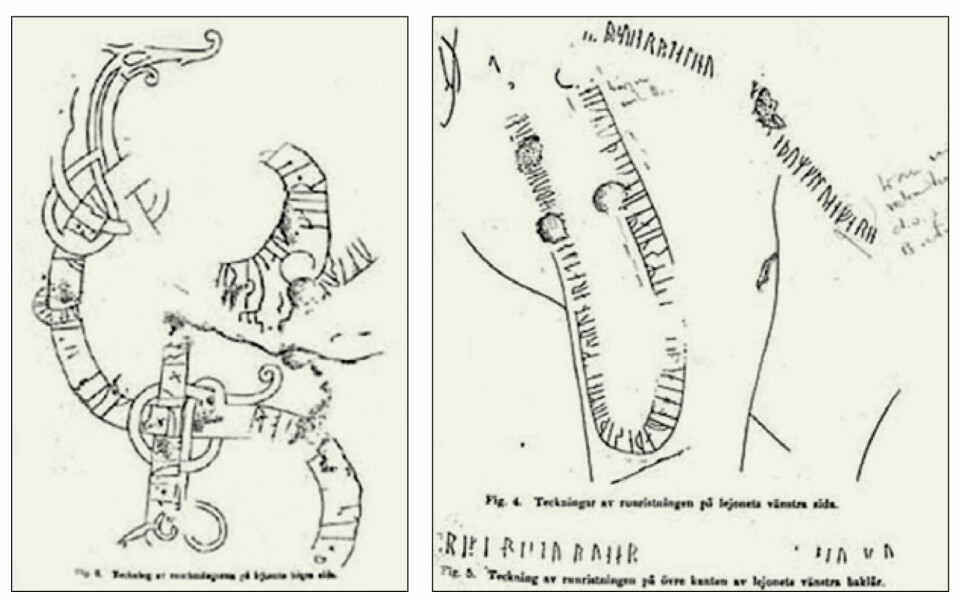

The Swedish researcher Erik Brate’s rendering in 1920 of the Swedish runes on the lion’s left side.

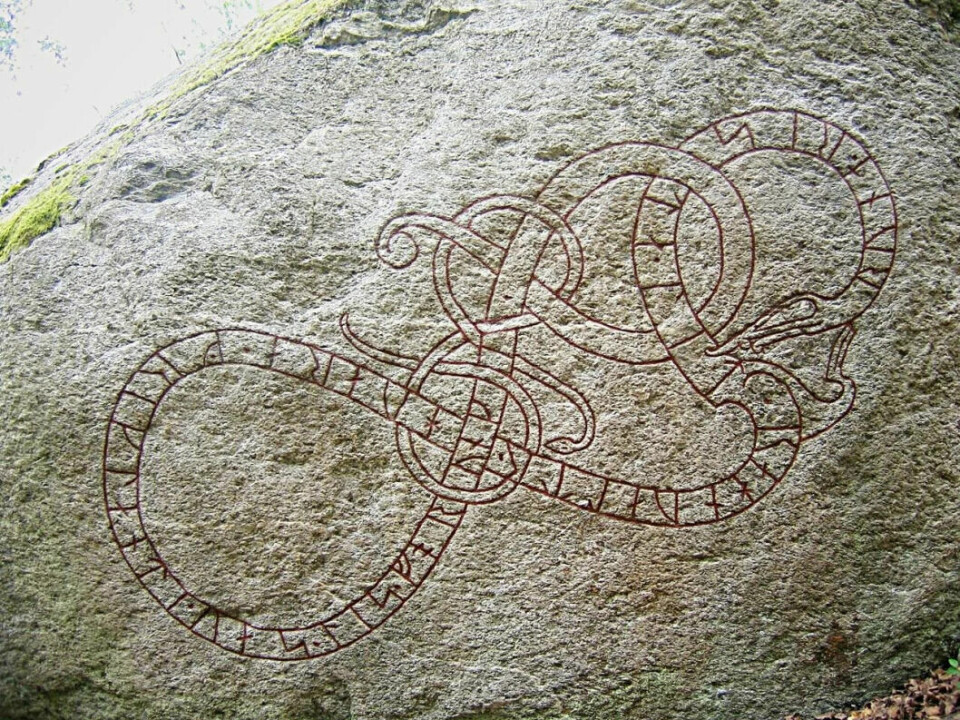

Thorgunn Snædal has found clear parallels in the shape of the runes on the Piraeus lion’s left side to Swedish runestones. There are many runestones in Sweden that mention the Varangians — the Vikings and their descendants who went to Byzantium. The person who made this runestone in Ed, north of Stockholm, describes when he served in the emperor’s guard in Constantinople: ‘Ragnvald carved the runes. He was in Greece, he was the chief of the warrior party.’ The runes in the Urnes style (named after the Norwegian Urnes stave church) shows that it was crafted at the end of the 11th century or the beginning of the 12th century.

(Photo: Berig / Wikimedia)

The Vikings were mercenaries

The Lion of Piraeus actually originates from the Athens port city of Piraeus.

It was carved out of marble in ancient Greece. The lion is almost 2,400 years old.

Varangians

From the end of the 9th century to the beginning of the 13th century, a large number of Swedes and Norwegians went to Constantinople (Miklagard) to serve as mercenaries for the emperors of Byzantium.

They were called Varangians or varings.

The Venetians took the lion from Piraeus in 1688, after wresting control of the port city of Athens from the Turks in the Ottoman Empire.

Then, for well over a thousand years, the lion stood as a famous symbol at the entrance to what in the Middle Ages became known as the Lion’s Harbour in Piraeus. The lion was so famous that the port of Piraeus was named after it.

The Vikings who had tagged the lion 700-800 years earlier were most likely Swedish and Norwegian mercenaries — called Varangians— in the service of the emperor in Byzantium.

Some have tried to read the name of the very last Norwegian Viking king Harald Hardrada (1015-1066) in the runes. But that interpretation is questionable.

The Emperor’s Guard of Norwegian and Swedish soldiers

A thousand years ago in Constantinople, which is today’s Istanbul, and which the Vikings called Miklagard (‘Great City’), the emperor of the Byzantine Empire had a bodyguard of Scandinavian mercenaries.

The Varangian guard were known as fearless, strong and daring soldiers.

They were also known to be ruthless.

The Varangians from Norway and Sweden were exotic figures in Byzantium. They probably also seemed threatening to many. The emperor’s guard of warriors was probably intended to deter generals and officers who might want to rebel against the emperor. Byzantine sources may indicate that they were also used for ‘dirty’ jobs.

For this, the veterans were well paid. Primarily in the form of looted goods ( ‘geld’).

There were many of them

Leif Inge Ree Petersen is a researcher in late antiquity and early medieval history at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim. When sciencenorway.no asks how many warriors went from Norway and Sweden as mercenaries to Byzantium, he answers:

“There were many of them. And we actually know the names of several hundred of them,” he said.

“Harald Hardrada alone is said to have had 500 men with him, according to the sagas. We don’t know if that’s right. But it doesn’t seem unrealistic,” he said.

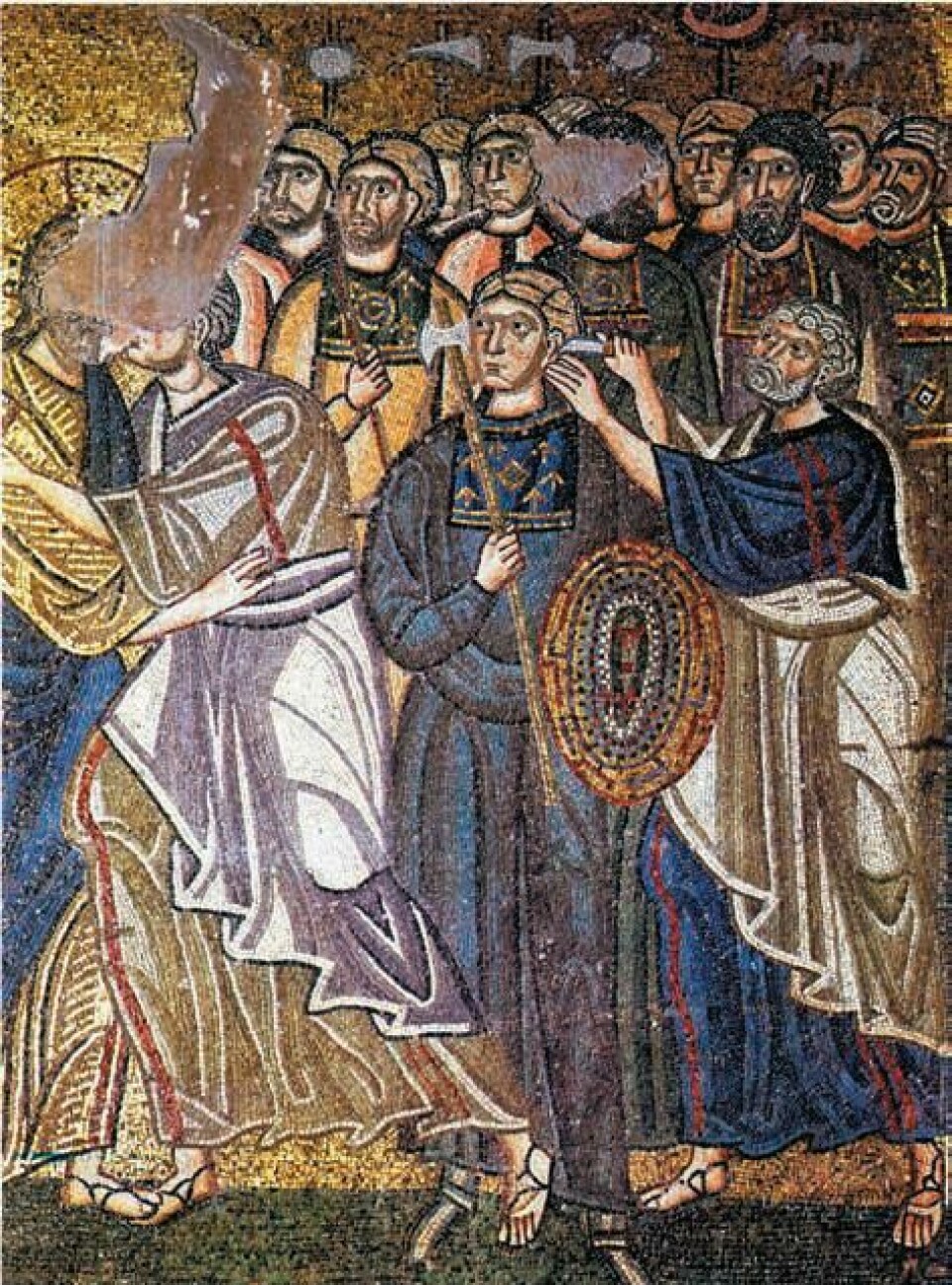

On the Greek island of Chios, next to today’s Turkey, is the monastery of Nea Moni. A mosaic here from the year 1043 depicts the Roman soldiers coming to arrest Jesus after the apostle Judas has singled him out with a kiss. When a Greek artist was to portray the brutal Roman soldiers a thousand years later, Leif Inge Ree Petersen thinks it’s likely he used Norwegian or Swedish mercenaries in the service of the emperor of Byzantium as models. The axes of the soldiers are more Nordic than Roman.

(Image: Princeton University / Wikimedia)

Examined the runes for 15 days

After examining the runes on the Piraeus Lion in Venice, rune researcher Thorgunn Snædal was quite certain that the runes on the lion were inscribed by three completely different groups of people from Scandinavia.

Three groups of Scandinavians who hardly knew each other.

Vikings from the north may have vandalised the lion in Piraeus with runes in three completely different situations.

The oldest carving on the lion’s left side — which Swedish Vikings were most certainly responsible for — dates from the 1020s, Snædal believes. The youngest carving on the lion’s right side — which Norwegian mercenaries in the service of Byzantium may have left behind —may be from sometime between the years 1070 and 1100, or several decades later.

Snædal spent a total of 15 days examining the lion’s runes.

She went to Venice at three different times of the year, to see how the light from the sun fell at different angles and cast varying shadows on the worn runes. Standing on a step ladder, she worked for hours studying the lion with her eyes and fingers, in the hopes of discovering more.

Swedish runes on the left side

The oldest runic inscription on the lion’s left side gives us an insight into the perilous life of the mercenaries.

It was drawn in memory of one of the Swedish Varangians’ comrades. The man was named Haursi, who had fallen.

Did he die in the war against the Bulgarians, which the Varangians helped win in 1018? Or was it while he was probably, like many other warriors, serving on board one of the ships in the emperor’s fleet in the Aegean? Or perhaps it was in a war against the Arabs in Serkland that he was killed?

In any case, the text establishes that the ‘farmer Haursi’ died before he could collect his rightful share of the war booty.

“For the Nordic mercenaries, it was natural to draw commemorative words with runes if a close friend or war comrade passed away,” Thorgunn Snædal said to Swedish Radio a few years back.

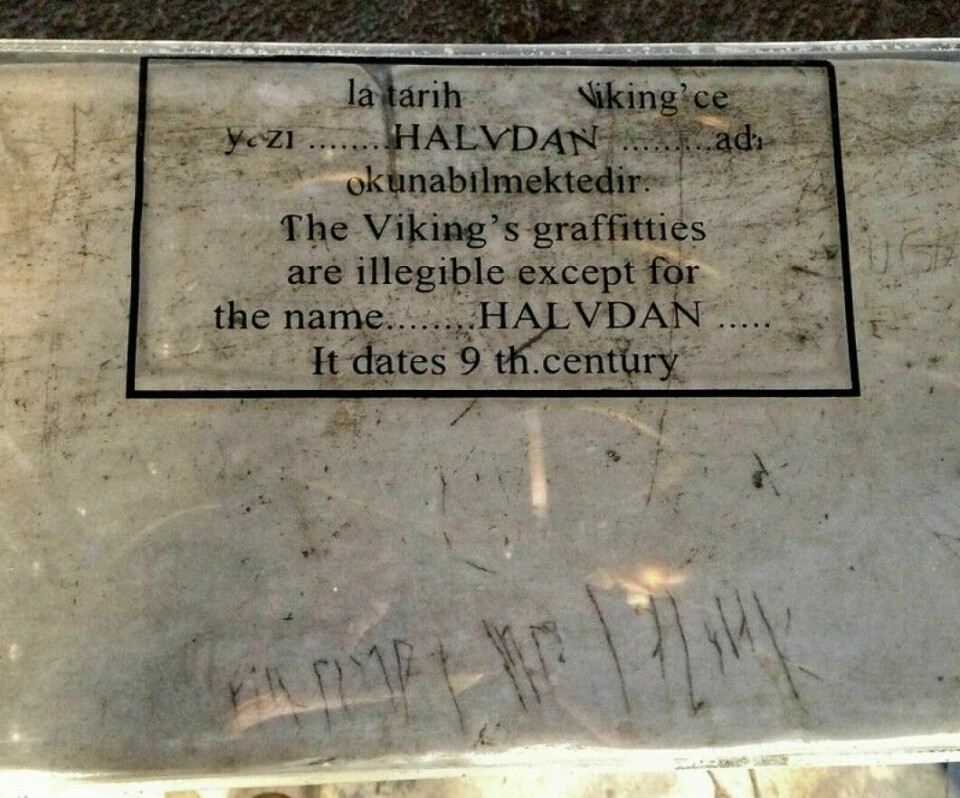

Once upon a time, around a thousand years ago, the Norwegian Viking Halfdan stood on the gallery in the fantastic Hagia Sofia church in Constantinople — at the time the world’s largest building — and left a tag ‘alfdan drew these runes’.

(Photo: Karl Gruenwald / Wikimedia)

‘Svear did this to the lion’

The rune researcher also thinks she could read ‘Svear did this on the lion’.

The inscription on the lion may thus be the very oldest text we know that mentions the word ‘svear’, meaning Swedes.

Piraeus and Athens were probably much-used resting places for warriors on their way between Constantinople and the battlefields in Bulgaria and in present-day Albania. At other times the warriors fought against soldiers from Serkland (Arabs). Or against Normans in Sicily. Or they hunted pirates and their treasures on Aegean islands with the Emperor’s blessing.

Snædal does not want to rule out that the Swedish warriors who carved the runes on the lion’s left side in memory of their fallen comrade Haursi may have been soldiers in Harald Hardrada’s army.

They were unlikely to be particularly skilled runemakers, the rune researcher said. From Erik Baste’s drawing from 1920 further up in the article, it is clear how they struggled quite a bit to get the ornamental loop in the commemorative text for their comrade Haursi.

The Swedish runes on the left side of the lion, as they appear today.

(Photo: Bård Amundsen)

Possible Norwegian runes on the right

The shortest runic inscription on the lion’s left rear is probably the middle one in time. It simply says ‘drængiaR ríst rúnar’ ‘Young (warriors) carved the runes’.

Plain and simple, just tagging to say you’ve been there, many will think.

The Varangians who carved these runes need not have been Swedish, Snædal concluded from the runic letters used.

Were they Norwegian? Or maybe Icelandic?

The youngest of the three runic inscriptions on the lion’s right side consists of around a hundred runes, like the oldest on the left side. It is carved in a beautiful runic loop and tells us that the person behind the vandalism of the ancient Greek lion must have mastered this beautiful form of writing well, Snædal said.

It is possible to recognise the runic loop in the dragon-like Urnes style on the famous portal of Urnes stave church.

Urnes is the oldest of Norway’s preserved stave churches and dates from around 1130.

Unfortunately, only 50 per cent of the supposedly Norwegian runes on the lion’s right side are legible, Snædal says. That’s compared to 80 per cent of the Swedish runes on the other side of the lion.

The Norwegian runes were hit extra hard by gunfire in the 17th century.

Åsmund carved the runes

The person who may have been Norwegian and who carved the runes is called Åsmund.

Åsmund the mercenary mastered the beautiful ornamentation that characterised the Viking Age. He must also have been skilled at runes.

The runes and ornamentation he carved into the lion are complicated and nicely composed, Snædal said. The shape of the runes on the lion’s right side tells the researcher that this drawing must have been made in the latter part of the 11th century.

Was it the Norwegian Varangians who in 1081 participated in the defence of the city of Dyrrachion (today’s Durrës in Albania) against attacking Normans from Sicily?

Or was it the Norwegian warriors who in 1092 went into battle from Piraeus to put down rebellions against the emperor in Crete and Cyprus? They may then have been accompanied by English warriors, fleeing to Byzantium from the Frenchman Wilhelm the Conqueror’s occupation of their homeland.

Thorgunn Snædal is not surprised that there were skilled runic warriors among the Nordic warriors who fought for Byzantium. She hopes that perhaps one day traces of the same talented Åsmund will be found somewhere in the Nordic countries.

But how is it that Swedish and Norwegian Vikings, with perhaps several decades between each episode, wrote runic graffiti on the Piraeus Lion from the time of Alexander the Great three separate times?

We simply don’t know.

The Greeks probably weren’t happy about graffiti being scratched into the flanks of the lion of ancient Greece. But there was hardly anyone who dared to stop the three groups of warriors from the Nordics who, over intervals of many years, tagged the Lion of Piraeus.

Along with the Lion of Piraeus, the Venetians also took three other ancient Greek lions with them in 1688, when they succeeded in capturing the city of Athens from the Ottoman Turks. All four lions now stand outside the Venetian naval headquarters Arsenal. Note the symbol of the city-republic of Venice on the wall, the winged Saint Mark’s lion with the Bible in its paw. The reason the Venetians were so keen to bring home these statues may have some connection to the city’s own symbol.

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!