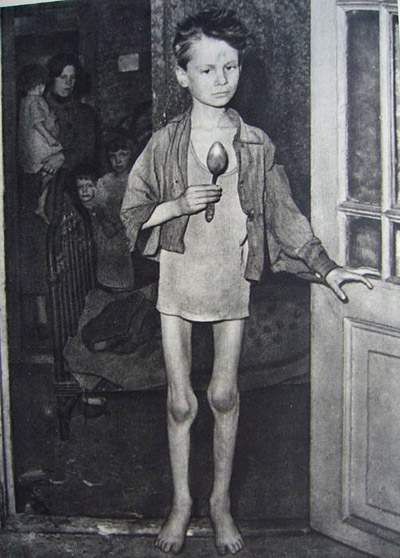

Malnourished boy in Amsterdam, 1945.

When I hear the word ‘famine’ I think of Ireland in the 1840s or Ethiopia in the 1980s. I don’t think of famines bringing death and suffering to western countries during my, or my parents’, lifetimes.

Yet that’s exactly what happened in the Netherlands in the winter of 1944-45. The Dutch call it de Hongerwinter (the Hunger Winter).

In the German-occupied north of the country a shortage of food combined with a bitterly cold winter caused the death of an estimated 20,000 people. Many others suffered lifelong health problems caused by malnutrition.

The famine struck towards the end of World War II. Food was already in short supply after years of Nazi occupation.

In September 1944 the Dutch government-in-exile called on railway workers to go on strike to prevent the German army transporting troops and supplies to the front. By then the Allies were less than 200km south of Amsterdam.

The strike worked but it also worsened food shortages. The German army carried out reprisals, took control of the railways and imposed a blockade, cutting off fuel and food supplies to the northwestern part of the Netherlands.

The Hunger Winter, like so many other famines, was no accident but a deliberate act to punish a civilian population.

B

B

omb damage in Stationsweg (Station Street), Leiden.

At the same time the Allies were carrying out a daring operation which aimed to bring the war in Europe to a rapid end. Their plan was to seize a series of bridges across the great rivers which flow east to west across the middle of the Netherlands, dividing the country in two.

If the Allies could capture those bridges they would control a corridor leading directly to Germany’s industrial heart.

That was the theory anyway. Operation Market Garden, fought from 17–25 September, 1944, was plagued by planning and intelligence failures as well as plain bad luck. It succeeded in liberating the southern half of the Netherlands but failed to capture the all-important bridges. The cost, both to civilians and soldiers, was enormous.

The story was immortalised in a book called A Bridge Too Far. It was made into a movie of the same name in 1977.

The result of Operation Market Garden’s failure — or, at best, mixed success — was that the south of the Netherlands, where my mother’s family lived, was liberated by the autumn of 1944. My mother and her siblings enjoyed unimaginable delicacies such as white bread and their home was frequented by Allied soldiers, thanks to my grandfather’s proficiency in English (a rare thing at that time).

My father’s family, however, lived in Leiden, in the densely populated northwest of the country. They remained under Nazi occupation for another nine months. They endured a bitterly cold winter and the last famine in Western Europe. But they survived.

. . . . .

A little while ago my parents were having a clean-out at their home in Auckland. My father found a tatty, yellowed exercise book he’d written in as a boy and threw it out.

My mother, however, never throws anything away. At times this is a source of frustration but on this occasion it was a godsend. It turned out the exercise book she rescued was a diary my father had kept during the Hunger Winter.

However, this wasn’t an ordinary diary. Instead of recording the normal things 13-year-old boys think about, it’s a detailed account of food rations, the barely edible things he had to eat, the soup kitchens that kept people alive, and the soaring cost of food.

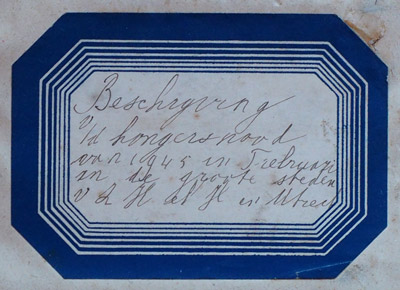

Title page of my father’s Hunger Diary.

Title page of my father’s Hunger Diary.

Towards the end of the famine, when food had all but disappeared, money had lost its meaning. People traded gold for a few morsels. Often they couldn’t get even that.

My father labelled his notebook “A description of the famine of February 1945 in the big cities of South Holland, North Holland and Utrecht”. I’ve given it a slightly catchier name, The Hunger Diary.

I’ve translated it as best I can, with his help. It isn’t written in chronological form like a regular diary; instead it’s a series of lists and observations. My father also glued in public notices cut from newspapers detailing rations, recipes for making sugar beets edible, and rules about who was eligible for candle rations.

Tulip bulbs (“disgusting!”) and sugar beets (“they stank!”) feature a lot, as does black-market price gouging. He writes a lot about potatoes, a rare and precious delicacy at that time.

I’ve shortened some entries to reduce repetition and occasionally juggled the order to improve flow. I’ve had to leave out whole sections which neither of us could read. I struggled to translate some words so I left them in Dutch and added an explanation.

I’ve tried to keep the original layout, including his underlining. I’ve added explanations and extra information in grey text to distinguish them from dad’s diary entries.

My father turned 14 in March 1945 as deaths from the famine peaked.

Soon afterwards the Swedish Red Cross started aerial bread drops. Germany surrendered on May 5 and three days later Canadian troops rolled into Leiden. Months would pass before food supplies were fully restored but the Hunger Winter was over.

. . . . .

The Hunger Diary

by Jan-Willem de Graaf, aged 13, February 1945

In February 1945 the food situation in Amsterdam, The Hague, Leiden, Rotterdam and Utrecht was very bad. It was a famine.

There was no gas, electricity, coal, fuel and more. Even hospitals had no heating.

The rations were as follows:

- 500 grams of bread per person per week. That meant one thin floddertje in the morning and two in the evening. [The word floddertje doesn’t translate well. It means something like a skinny, limp slice.]

- 1 kg potatoes per person per week. But sometimes you had to wait in the queue if they hadn’t arrived yet, or sometimes you got tulip bulbs instead, which were disgusting.

- Sometimes 250 grams of pea flour.

- Only very small children got a little bit of milk. Children up to 15 got a bit of milk powder.

The famine was so bad people ate sugar beet and flower bulbs — at first tulip bulbs were mashed together with potatoes, but later we had to eat them on their own.

Children eat their daily soup ration. Photo taken illegally and at considerable risk by Menno Huizinga.

Children eat their daily soup ration. Photo taken illegally and at considerable risk by Menno Huizinga.

Here follows some prices for food:

- 400g loaf of bread: 15-25 guilders. [In 1940 the average weekly income of a Dutch household was 20-25 guilders. So that’s a week’s pay for one loaf. Before the war, according to the Dutch Bureau of Statistics, a loaf of bead cost 18 cents. The price had gone up 100-fold.]

- Butter: 7-15 guilders per 500g but you couldn’t get it anyway.

- Milk: 10 guilders per litre. Later you could sometimes get a half litre of milk from a farmer for a bag of vegetable peelings [which were used as cattle feed]. Some people collected the peelings from houses and ate them.

- You couldn’t get matches anywhere. People paid 10 guilders for a packet. Candles cost 10 guilders each.

- Crazy prices were offered for wheat. You couldn’t get sugar.

- Bicycles cost thousands of guilders. For a single black-market tyre you paid as much as for three or four bicycles before the war. [The Germans seized almost all Dutch bicycles early in the war, hence their scarcity.]

- The price of cigars was crazy, sometimes 12 guilders each. Cigarettes cost 3 guilders each.

- There were no sweets at all. What you got for one cent in 1944 you couldn’t buy in 1945 for 2 guilders.

- Apples cost 13 guilders per kg.

- Meat was about 40 guilders for 500g.

In the city there wasn’t a single tree left. They’d all been cut down by people hacking pieces off at night. People seen carrying wood were shot. [With no fuel for heating or cooking trees were cut down, piece by piece, for firewood. It had to be done carefully because the penalty for breaking the night-time curfew was severe.]

People broke off anything that was made of wood. There were often accidents as a result, like the house that fell down in Amsterdam killing two people [because so much wood had been removed].

Once, at the weigh-house in Leiden, you could get cabbage with a ration card. When they had a little bit of red cabbage the queue was 75-80 metres long.

People queue for food rations. Photo source: Beeldbank WO2

People queue for food rations. Photo source: Beeldbank WO2

People started arriving at hospital with hunger oedema [fluid retention in the face, feet and legs caused by malnutrition].

In Amsterdam 80 cases of malnutrition were taken to hospital each day. They could not be saved.

When people in North Holland went to the countryside to get potatoes they had to endure terrible deprivation and cold because they were outside all night. Often they got so hungry they ate the potatoes before they got home.

Some mothers sent their 13-14-year-old children to Friesland [a northern province] because they couldn’t get food any more. Old people too left everything behind and went to the Achterhoek [a rural area in the east where the food situation was better]. Some people offered to exchange everything they owned for some food.

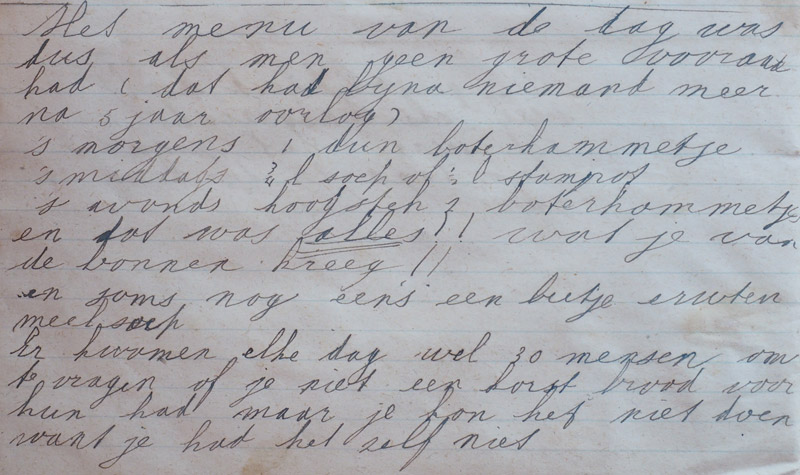

If you didn’t have big reserves of food at home (which no one did after five years of war) the daily menu was like this:

- One skinny little sandwich in the morning.

- ¾ litre soup or ½ litre stamppot [a dish traditionally made with mashed potatoes and one other vegetable].

- At most one little sandwich in the evening.

That was all you got with ration cards! (And sometimes a little bit of pea-flour soup.) Every day about 30 people came to your door to ask if you had a crust of bread. But you couldn’t give them anything because you didn’t have any yourself.

Malnourished boy in Amsterdam, 1945.

Malnourished boy in Amsterdam, 1945.

In January a candy ration card came out. But of course you couldn’t get anything with it.

People often collapsed on the street or in church on Sundays due to lack of food.

From 8 o’clock in the evening until 4 o’clock in the morning no one was allowed outside on the street.

In Amsterdam a sick child needed potatoes. Potatoes could be bought only for the scandalous price of 2.50 guilders each. She got half a potato one day and the other half the next day.

People also ate cats. Apparently they tasted good.

After a while you couldn’t even get food from farmers, even with gold. Many people gave their wedding rings for a bit of rye. People would spend all day walking to a farm to buy food or swap their clothing for something to eat, but they’d come back with nothing.

[A recollection from my father: We were fortunate because my father was a dentist. Sometimes he would do dental work for farmers in exchange for wheat. We’d go to someone’s house who had hooked up a coffee grinder to a bicycle, and we’d use it to grind the wheat and make flour. Then my mother would bake bread.]

The central kitchen

[There were 13 central kitchens around Leiden. Each handed out daily rations of warm food, usually a watery soup.]

When you handed in a potato coupon at the central kitchen you got a food card for ½ litre stamppot or ¾ litre soup or mashed sugar beet. Sometimes you had to wait 3½ hours in the cold before you got some watery soup or sugar beet porridge — that was water with sugar beet and pieces of glubber. [Glubber is a made-up word. Just imagine something rubbery and disgusting.]

The stamppot was made from potatoes and beets and was often sour.

Excerpt from my father’s Hunger Diary.

Excerpt from my father’s Hunger Diary.

The soup was thin pea-flour soup or bean soup. Sometimes it was orange, sometimes purple or other filthy colours. All week long they served soup, sometimes porridge. Anytime potatoes arrived the Moffen would confiscate them. [Moffen is a slang term for German soldiers. ‘Krauts’ is the closest I can think of in English but Moffen is more insulting.]

The elderly had priority in the queue and even though they were old they would hit each other over the heads with their pans [to get to the front of the queue].

[Another recollection from my father: I also remember the big grey seagulls, they came into the city to find scraps because there was no food for them any more on the coast. There was nothing for them in the city of course. I saw them attacking little kids in desperation. It’s the reason I hate seagulls even now.]

Electricity

In the evenings people mostly sat in the dark or in a little bit of light from a candle or an oil lamp. The buildings where the Moffen stayed had electricity. There was a lot of mucking about with wires and some people managed to get some electricity.

[My father adds: Stealing electricity was common. My brother Frans somehow managed to get some electricity from somewhere. Some Germans were quartered in the school behind our house in the Aalmarkt (a street) and he managed to put a line from there to our house. And then the Germans staying at the school saw we had light and came to our house. They were very angry and demanded to know where we got our electricity from. We had to give it up. They told us they were going to shoot through the window when they saw our light, but instead they decided to come into the house and have a look first. I was sitting in front of the window at the time.]

Scene from the liberation of Leiden. Photo taken on the Breestraat, the street where my father lived after the war.

Scene from the liberation of Leiden. Photo taken on the Breestraat, the street where my father lived after the war.

Postscript: As I write this another corner of Europe faces famine. People in the besieged Ukrainian city of Mariupol have been without food supplies, running water or electricity for a month. It reminds me that Ukraine was the centre of another 20th century famine, known as the Holodomor (literally ‘killing by hunger’). In 1932-33 millions of Ukrainian peasants died during Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s forced collectivisation of agriculture. Estimates for the number of dead vary widely but recent studies suggest a toll of about 3.5 million.

More information:

Litsen to an excellent BBC audio programme about the Hunger Winter, featuring interviews with survivors and historians.

Explore a portal packed with photos, recordings and articles about the Hunger Winter (in Dutch only).

Head to Wikipedia to learn more about the Hunger Winter or read a blow-by-blow account of Operation Market Garden and how it went wrong.

Other Dutch-themed stories I’ve written include The far-reaching wake of the waka and the more personal Being Dutch: What my heritage means to me.

Related Post

La desgarradora historia real detrás de la infame fotografía niños en venta; de 1948

El desastre del vuelo de los Andes: un avión que transportaba a 45 personas se estrelló y los supervivientes recurrieron al canibalismo antes de ser rescatados, 1972

Los soldados regresan a casa al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El RMS Queen Elizabeth no estaba abarrotado, los soldados simplemente corrieron hacia la cubierta cuando llegaron a Nueva York.

Los mineros de Charbonnagge de Mariemont-Bascoup se apretujaron en el ascensor de una mina de carbón después de un día de trabajo. Fotografía tomada en Bélgica en c. 1900.

The lives of Chinese people in the late Qing Dynasty through a series of rare photos

Another relic from Alice in Wonderland, a photograph depicting Alice and the dormouse, 1887.