The Women’s Timber Corps (WTC), affectionately referred to as the “lumberjills,” emerged as a division of the renowned Women’s Land Army in April 1942.

During World War II, while soldiers fought on battlefields abroad, a different kind of warrior emerged on the home front in the United Kingdom.

They were known as the “Land Girls”, members of the Women’s Land Army (WLA), a civilian organisation created to boost agricultural production and compensate for the shortage of male farm workers who had gone to fight.

The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was originally constituted during the First World War but experienced a significant revival in June 1939, on the cusp of the Second World War.

This reformation was prompted by Britain’s foresight into the impending need for increased agricultural output to sustain the nation during the conflict.

A Land Army girl using a Fordson tractor to plough a field at the Agricultural College at Cannington during the Second World War.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries took the lead in revitalising the WLA, targeting women to replace the vast numbers of men conscripted into military service.

In the early stages, recruitment proved challenging, with only a tepid response from potential enlistees. Many women were initially reluctant to join due to the hard labour and rural isolation associated with farm work.

Propaganda

However, as the war intensified and the necessity for home-grown produce became undeniably critical to national security, the appeal of the Land Army grew. Propaganda efforts were stepped up, highlighting the patriotic importance of the WLA and appealing to the spirit of national service among women.

New recruit to the Women’s Land Army, Iris Joyce, learns to drive the horse-drawn hay rake as part of her training at the Northampton Institute of Agriculture near Moulton in 1942.

New recruit to the Women’s Land Army, Iris Joyce, learns to drive the horse-drawn hay rake as part of her training at the Northampton Institute of Agriculture near Moulton in 1942.

By 1944, the ranks of the Land Girls had expanded dramatically, with membership exceeding 80,000. This surge was not just a reflection of growing patriotic fervour but also of the strategic initiatives undertaken by the government.

Training programmes were implemented to swiftly equip new recruits with the necessary skills for agricultural work, ranging from crop planting to livestock handling.

A Land Girl carrying a large forkful of straw at the Women’s Land Army training centre at Cannington in Somerset during 1940.

A Land Girl carrying a large forkful of straw at the Women’s Land Army training centre at Cannington in Somerset during 1940.

Moreover, the government took steps to enhance the appeal of the Land Army, offering wages that, while still below those of male farm workers, were competitive with other women’s work available at the time. Uniforms were provided, which not only equipped the women for their new roles but also instilled a sense of unity and purpose.

Land Girls of World War One

The Women’s Farm and Garden Union, established in 1899, made significant strides in February 1916 when they approached Lord Selborne with a delegation.

The Ministry of Agriculture, under Selborne’s stewardship, agreed to fund a Women’s National Land Service Corps with a grant of £150.

Women under training to be milkmaids during the first world war.

Women under training to be milkmaids during the first world war.

Louise Wilkins was appointed to lead this new entity, which was primarily focused on recruiting women for emergency war work.

The mission was not only to enhance recruitment efforts but also to disseminate propaganda promoting the noble cause of women from all social classes engaging in agricultural labour.

Read more: Peoples Have Been Roaming our Countryside for 900,000 Years

The members of this newly formed organisation were tasked not with direct agricultural work themselves but with mobilising others, such as village communities, to take up these roles. By the end of 1916, they had enlisted 2,000 volunteers, although they estimated a need for 40,000.

A female agricultural labourer oversees cows about to milked at a British farm during the First World War.

A female agricultural labourer oversees cows about to milked at a British farm during the First World War.

At the suggestion of the Women’s National Land Service Corps, a formal Land Army was established. This organisation continued to oversee recruitment, and its rapidly expanding network played a crucial role in launching the “Land Army”.

By April 1917, they had received over 500 inquiries, with 88 individuals joining and taking on roles as group leaders and supervisors within this new Land Army.

A female farm hand feeding poultry, 1918.

A female farm hand feeding poultry, 1918.

Compensation

Ultimately, the Land Army would come to employ 23,000 workers, effectively replacing the 100,000 agricultural workers who had been recruited into the military. The women were compensated at a rate of 18 shillings per week, which could be increased to 20 shillings if their efficiency warranted it.

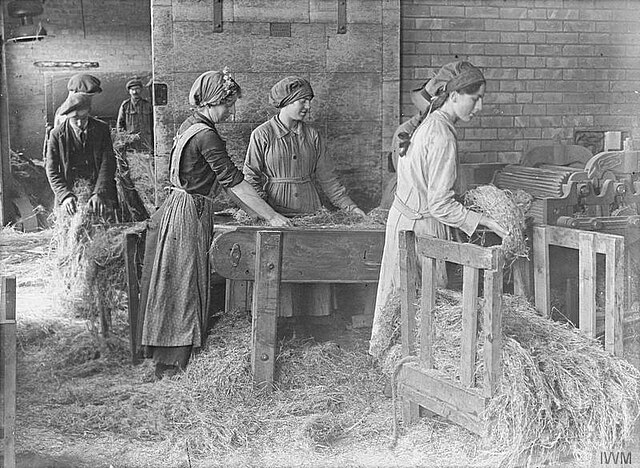

Female workers evening up the lengths of flax for breaking during the first world war.

Female workers evening up the lengths of flax for breaking during the first world war.

Although 23,000 was a substantial number, it is estimated that during the First World War, around 300,000 women were engaged in agricultural work across the country.

Read more: Medieval Bridge in Exeter, a Very Rare Relic

A Good Service Ribbon was awarded to those women who met the eligibility criteria. In January 1918, the first issue of The Landswoman was published.

This magazine served as the official monthly publication for the Women’s Land Army and the Women’s Institutes. The organisation was eventually disbanded in November 1919.

Land Girls of World War Two

As the likelihood of war increased, the British government sought to boost domestic food production. In April 1939, the introduction of peacetime conscription, a first in British history, led to a shortfall of agricultural workers.

Sylvia Smith was a shorthand typist before beginning her Land Army training at the Northampton Institute of Agriculture. Here she ties beans or peas to stakes, 1942.

Sylvia Smith was a shorthand typist before beginning her Land Army training at the Northampton Institute of Agriculture. Here she ties beans or peas to stakes, 1942.

To address this, the government re-established the Women’s Land Army in July 1939 under the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, appointing Lady Denman as its honorary head. Initially reliant on volunteers, the ranks were later bolstered by conscription, reaching over 80,000 members by 1944.

Read more: Costermongers, Who Exactly Are They?

Inez Jenkins, who had previously assisted Lady Denman during the WLA’s establishment, served as Chief Administrative Officer until 1948, with Amy Curtis succeeding her as the final Chief. The WLA was officially disbanded on 30 November 1950.

Three Land Girls harvest flax on a farm in Huntingdonshire during 1942.

Three Land Girls harvest flax on a farm in Huntingdonshire during 1942.

Industrial Cities

While the majority of the Land Girls were from rural areas, over a third originated from London and the industrial cities in the north of England.

A separate branch, the Women’s Timber Corps, was formed in 1942 to support the forestry industry. Its members, known colloquially as “Lumber Jills”, continued their work until the corps was disbanded in 1946.

Land Girl Iris Joyce leading a bull at a farm somewhere in Britain during 1942.

Land Girl Iris Joyce leading a bull at a farm somewhere in Britain during 1942.

Iris had previously been a typist but after four weeks training at the Northampton Institute of Agriculture, she is now confident to deal with such animals and all aspects of her work in the Women’s Land Army.

During the conflict, in 1943, a lady called Amelia King faced discrimination when she was initially refused work because of her race. This decision was reversed following intervention by her MP, Walter Edwards, who raised the issue in the House of Commons.

Women’s Timber Corps

The Women’s Timber Corps (WTC), also known as the “Lumber Jills”, was a critical yet often overlooked division of the Women’s Land Army during World War II.

Established in 1942, this branch was specifically created to address the urgent need for timber, a resource vital for the war effort, which was used in everything from pit props in the mining industry to telegraph poles and packaging crates.

Land Army girls sawing larch poles to lengths for pit props.

Land Army girls sawing larch poles to lengths for pit props.

Women’s Timber Corps Training Camp at Culford, Suffolk.

The primary role of the Women’s Timber Corps was to ensure the steady supply of wood needed by the war economy. Women recruited into the WTC were trained in forestry work, a sector previously dominated by men.

Their tasks included felling trees, operating sawmills, and transporting timber, challenging work that required significant physical strength and resilience.

Land Army girls sawing larch poles for use as pit props at the Women’s Timber Corps training camp at Culford in Suffolk.

Land Army girls sawing larch poles for use as pit props at the Women’s Timber Corps training camp at Culford in Suffolk.

The Lumber Jills worked across the United Kingdom, often in remote woodlands and under harsh conditions.

Despite the physical demands and the initial skepticism they faced, these women proved indispensable to the timber trade during the war.

They not only met but frequently exceeded production targets, significantly bolstering Britain’s timber reserves at a critical time.

Accommodations

Accommodations for the Lumber Jills were similar to those of their counterparts in agriculture: basic and functional, typically in wooden huts or billets close to their working sites. These conditions, while spartan, helped forge a strong sense of community and shared purpose among the women.

Jean Sheehan, a Land Army girl, chopping a tree.

Jean Sheehan, a Land Army girl, chopping a tree.

Despite their vital contributions, the Women’s Timber Corps was disbanded in 1946, a few years before the Women’s Land Army concluded its operations. Recognition of the Lumber Jills’ efforts was slow to materialise.

Read more: What Exactly is a Forest, it Doesn’t Mean Trees

Recognition for their service finally came in the form of a commemorative badge awarded by the government in 2007, similar to the recognition given to the Land Girls.

This acknowledgment was a testament to the essential work carried out by the Women’s Timber Corps during a time of national crisis.

Women’s Land Army and Women’s Timber Corps memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum, Arlewas, Staffordshire

Women’s Land Army and Women’s Timber Corps memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum, Arlewas, Staffordshire

The Life of The Land Girls

The life of a Land Girl during World War II was characterised by significant challenges and a demanding adjustment from urban to rural settings. Many of these women, previously accustomed to city life, were suddenly thrust into the harsh realities of agricultural labour.

College girls breaking the flax on a farm in Yeovil, Somerset during the first world war.

College girls breaking the flax on a farm in Yeovil, Somerset during the first world war.

Their responsibilities were diverse and strenuous; they included ploughing fields, sowing and reaping crops, as well as managing livestock and milking cows.

The physical demands of these tasks were amplified by the necessity to work extensive hours under all kinds of weather conditions, which tested their physical endurance and mental resilience.

After a hard day’s work on the Lincolnshire farm where they are stationed, these members of the Women’s Land Army don’t waste time before getting to bed. It’s still daylight outside as the girls prepare for a good night’s rest. 12th January 1940. Courtesy of Catherine Procter.

After a hard day’s work on the Lincolnshire farm where they are stationed, these members of the Women’s Land Army don’t waste time before getting to bed. It’s still daylight outside as the girls prepare for a good night’s rest. 12th January 1940. Courtesy of Catherine Procter.

Despite these rigorous demands, the Land Girls displayed extraordinary determination and spirit. Their accommodations were typically modest, with many residing in converted farm outbuildings or cramped hostels, which added another layer of difficulty to their daily lives.

Read more: Oakley Down Cemetery 6000 Years of History

Visually, the Land Girls were distinguished by their distinctive uniforms, which consisted of green jumpers, brown trousers, and felt hats.

This attire did more than serve a practical function; it symbolised a radical shift from traditional female roles and dress norms.

Challenges and Discrimination

Despite their indispensable contributions to the British war effort, the Land Girls encountered substantial challenges and faced widespread discrimination.

Initially, their agricultural work did not receive the same honour or public recognition as the military endeavours of the armed forces.

Financial disparities were evident as well, as they received wages that were markedly lower than those of their male counterparts who remained in civilian jobs. Additionally, their fight for official recognition was a persistent struggle, reflecting societal reluctance to accept women in traditionally male-dominated roles.

Read more: Medieval Pillow Mounds, What Are They?

The physical demands of their duties, coupled with their non-traditional uniforms, often subjected the Land Girls to societal scrutiny and prejudice.

Their practical attire, designed for the rigours of farm work, clashed with contemporary expectations of women’s dress, leading to misjudgements and social stigma.

Land Army girls arriving with a protest poster. 700 Land Army girls from all parts of the country voicing their grievances at a meeting held in Caxton Hall, London demanding equal pay for equal work.

Land Army girls arriving with a protest poster. 700 Land Army girls from all parts of the country voicing their grievances at a meeting held in Caxton Hall, London demanding equal pay for equal work.

Nevertheless, as the war advanced and the essential nature of their work became increasingly apparent, public opinion began to change.

The nation depended heavily on their efforts, especially during periods of severe rationing and food shortages. The reliability of food production, a critical aspect of the home front war effort, rested largely on their shoulders.

Read more: First Fleet Convicts Transported to Australia

By the end of World War II, the perception of the Land Girls had transformed significantly. They had garnered a new level of respect and appreciation from the British public.

Legacy and Recognition of The Land Girls

Following the cessation of hostilities, the Women’s Land Army was gradually phased out, culminating in the formal dissolution of the organisation in 1950.

For decades subsequent to their disbandment, the vital contributions of the Land Girls remained largely overshadowed within the broader war narrative.

Their stories, crucial to the nation’s survival during the war, were often omitted from historical accounts, leaving their efforts largely un-celebrated.

This oversight persisted until significant societal and historical reassessments took place, which recognised the indispensable roles that these women had played.

Recognition of their contributions began to emerge slowly, reflecting a growing appreciation for the diverse roles undertaken by various groups during the war.

The turning point in their recognition came in 2009, when the British government took a decisive step to formally honour these women. A commemorative badge was issued to all surviving members of the Women’s Land Army, symbolising official acknowledgment of their invaluable service during World War II.

Related Post

La desgarradora historia real detrás de la infame fotografía niños en venta; de 1948

El desastre del vuelo de los Andes: un avión que transportaba a 45 personas se estrelló y los supervivientes recurrieron al canibalismo antes de ser rescatados, 1972

Los soldados regresan a casa al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El RMS Queen Elizabeth no estaba abarrotado, los soldados simplemente corrieron hacia la cubierta cuando llegaron a Nueva York.

Los mineros de Charbonnagge de Mariemont-Bascoup se apretujaron en el ascensor de una mina de carbón después de un día de trabajo. Fotografía tomada en Bélgica en c. 1900.

The lives of Chinese people in the late Qing Dynasty through a series of rare photos

Another relic from Alice in Wonderland, a photograph depicting Alice and the dormouse, 1887.