Siberian Princess reveals her 2,500 year old tattoos

The ancient mummy of a mysterious young woman, known as the Ukok Princess, is finally returning home to the Altai Republic this month.

She is to be kept in a special mausoleum at the Republican National Museum in capital Gorno-Altaisk, where eventually she will be displayed in a glass sarcophagus to tourists.

For the past 19 years, since her discovery, she was kept mainly at a scientific institute in Novosibirsk, apart from a period in Moscow when her remains were treated by the same scientists who preserve the body of Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin.

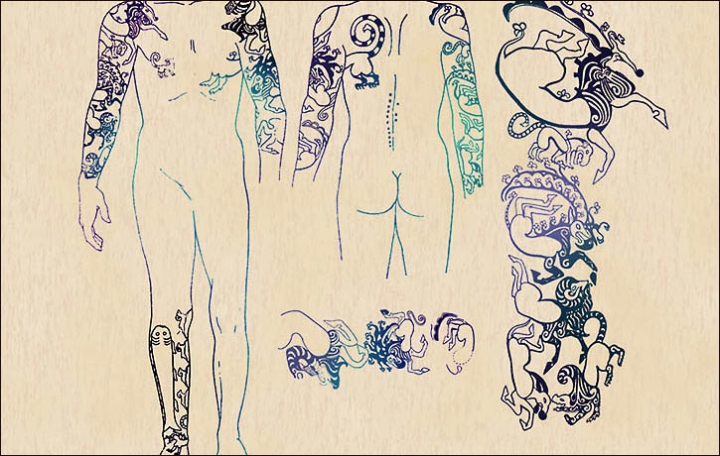

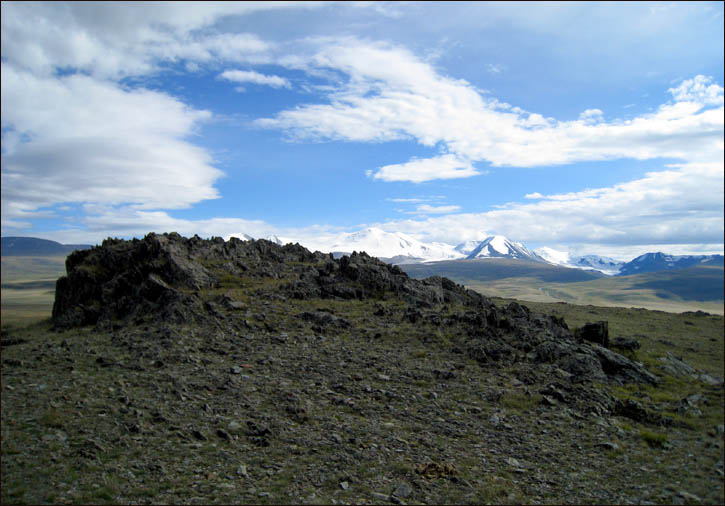

To mark the move ‘home’, The Siberian Times has obtained intricate drawings of her remarkable tattoos, and those of two men, possibly warriors, buried near her on the remote Ukok Plateau, now a UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage site, some 2,500 metres up in the Altai Mountains in a border region close to frontiers of Russia with Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan.

They are all believed to be Pazyryk people – a nomadic people described in the 5th century BC by the Greek historian Herodotus – and the colourful body artwork is seen as the best preserved and most elaborate ancient tattoos anywhere in the world.

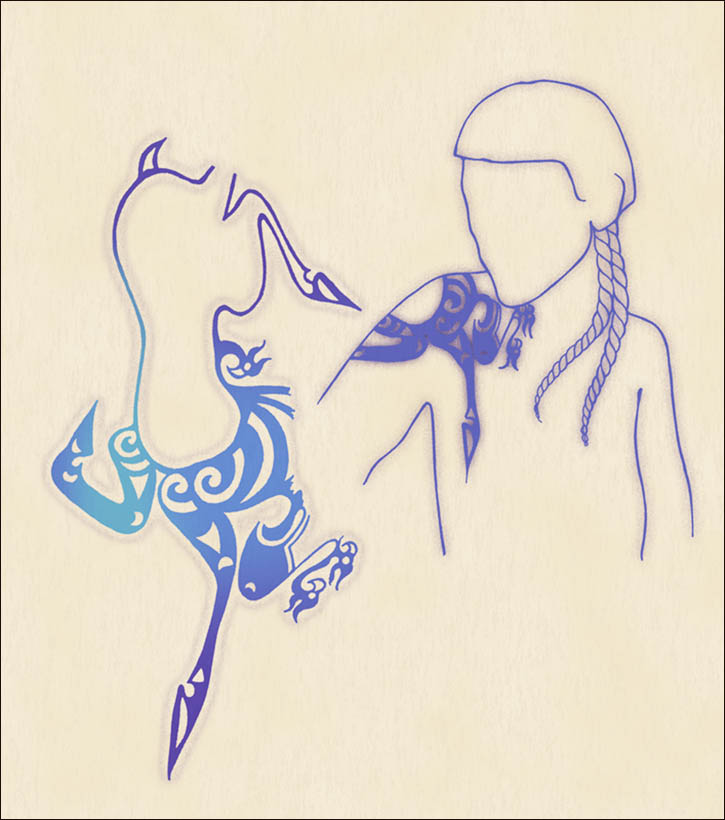

To many observers, it is startling how similar they are to modern-day tattoos.

The remains of the immaculately dressed ‘princess’, aged around 25 and preserved for several millennia in the Siberian permafrost, a natural freezer, were discovered in 1993 by Novosibirsk scientist Natalia Polosmak during an archeological expedition.

Buried around her were six horses, saddled and bridled, her spiritual escorts to the next world, and a symbol of her evident status, perhaps more likely a revered folk tale narrator, a healer or a holy woman than an ice princess.

There, too, was a meal of sheep and horse meat and ornaments made from felt, wood, bronze and gold. And a small container of cannabis, say some accounts, along with a stone plate on which were the burned seeds of coriander.

‘Compared to all tattoos found by archeologists around the world, those on the mummies of the Pazyryk people are the most complicated, and the most beautiful,’ said Dr Polosmak. More ancient tattoos have been found, like the Ice Man found in the Alps – but he only had lines, not the perfect and highly artistic images one can see on the bodies of the Pazyryks.

‘It is a phenomenal level of tattoo art. Incredible.’

While the tattoos, preserved in the permafrost, have been known about since the remains were dug up, until now few have seen the intricate reconstructions that we reveal here.

‘Tattoos were used as a mean of personal identification – like a passport now, if you like. The Pazyryks also believed the tattoos would be helpful in another life, making it easy for the people of the same family and culture to find each other after death,’ added Dr Polosmak. ‘Pazyryks repeated the same images of animals in other types of art, which is considered to be like a language of animal images, which represented their thoughts.

‘The same can be said about the tattoos – it was a language of animal imagery, used to express some thoughts and to define one’s position both in society, and in the world. The more tattoos were on the body, the longer it meant the person lived, and the higher was his position. For example the body of one man, which was found earlier in the 20th century, had his entire body covered with tattoos. Our young woman – the princess – has only her two arms tattooed. So they signified both age and status.’

The tattoos on the left shoulder of the ‘princess’ show a fantastical mythological animal: a deer with a griffon’s beak and a Capricorn’s antlers. The antlers are decorated with the heads of griffons. And the same griffon’s head is shown on the back of the animal.

The mouth of a spotted panther with a long tail is seen at the legs of a sheep. She also has a deer’s head on her wrist, with big antlers. There is a drawing on the animal’s body on a thumb on her left hand.

On the man found close to the ‘princess’, the tattoos include the same fantastical creature, this time covering the right side of his body, across his right shoulder and stretching from his chest to his back. The patterns mirror the tattoos on a much more elaborately covered male body, dug from the ice in 1929, whose highly decorated torso is also reconstructed in our drawing here.

His chest, arms, part of the back and the lower leg are covered with tattoos. There is an argali – a mountain sheep – along with the same deer with griffon’s vulture-like beak, with horns and the back of its head which has a griffon’s heads and an onager drawn on it.

All animals are shown with the lower parts of their bodies turned inside out. There is also a winged snow leopard, a fish and fast-running argali.

To some, the clash depicted on the tattoes between vultures and hoofed animals corresponds to the conflict between two worlds: a predator from the lower, chthonian world against herbivorous animals that symbolise the middle world.

Dr Polosmak is intrigued at way so little has changed.

‘We can say that most likely there was – and is – one place on the body for everyone to start putting the tattoos on, and it was a left shoulder. I can assume so because all the mummies we found with just one tattoo had it on their left shoulders.

‘And nowadays this is the same place where people try to put the tattoos on, thousands of years on.

‘I think its linked to the body composition… as the left shoulder is the place where it is noticeable most, where it looks the most beautiful. Nothing changes with years, the body stays the same, and the person making a tattoo now is getting closer to his ancestors than he or she may realise.

‘I think we have not moved far from Pazyryks in how the tattoos are made. It is still about a craving to make yourself as beautiful as possible.

‘For example, about the British. A lot of them go on holiday to Greece, and when I’ve been there I heard how Greeks were smiling and saying that a British man’s age can be easily understood by the number of tattoos on his body.

‘I’m talking the working class now. And I noticed it, too. The older a person, the more tattoos are on his body.’

FINDING THE ICE-CLAD ‘PRINCESS’

‘It was an international research programme, devoted to the Pazyryk Iron Age culture,’ said Academician Vyacheslav Molodin, deputy director of Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences.

To modern man, the only way in is by helicopter, yet in ancient times this was on the ‘southern steppe road’ used by migrating nomadic peoples in the pre-Christian and Dark Ages.

‘The burial mound with the ‘princess’ seemed to be half deserted, with big holes which border guards dug to use the stones.

‘It seemed less than hopeful. But Natalya Polosmak was determined that we had to start working on it…..

‘To our utter surprise, there was an untouched burial chamber inside the mould.

‘We started working on opening the ‘ice lense’ – the burial inside the mould was filled with ancient ice.

‘We started to melt the ice. First the skeletons of six horses appeared, some with preserved wooden decorations on the harness, some with coloured saddles made from felt.

‘On one of the saddles was a picture of a jumping winged lion.

‘Then the burial room appeared from under the ice. It was made from larch logs. Inside stood a massive hollowed wooden log with a top, shut with bronze nails. Inside the log was all filled with ice.

‘It was a tanned arm that appeared from under the ice first.

‘A bit more work and we saw remain of a young woman, lying inside the log in a sleeping position, with her knees bent.

‘She was dressed in a long shirt made from Chinese silk, and had long felt sleeve boots with a beautiful decoration on them.

‘Chinese silk before was only found in ‘Royal’ burials of the Pazyryk people – it was more expensive than gold, and was a sign of a true wealth. ‘There was jewellery and a mirror found by the log.

‘The great value of Pazyryk burials is that they were all made in permafrost, which helped the preservation.

‘It was quite unusual to have a single Pazyryk burial. Usually men from this culture were buried with women.

‘In this case, her separate burial might signify her celibacy, which was typical for cult servants or shamans, and meant her independence and exceptionality.

‘She had no weapons buried with her, or on her, which means that she certainly was not one of the noble Pazyryk women-warriors.

‘Most likely, she possessed some special knowledge and was a healer, or folk tale narrator.

‘From the inside the mummy was filled with herbs and roots. Her head was completely shaved, and she wore a horse hair wig.

‘On top of the wig there was a symbol of the tree of life – a stick made from felt, wrapped with black tissue and decorated with small figures of birds in golden foil.

‘On the front of the wig, like a cockade, was attached a wooden carving of deer.

‘The princess’s face and neck skin was not preserved, but the skin of her left arm survived, and we saw a tattoo, going all along it.

‘She had tattoos on both arms, from shoulders to wrists, with some on the fingers, too. The best preserved of all was a tattoo on her left shoulder, featuring a deer with griffon’s beak and a Capricorn’s horns. A bit below is a sheep, with a snow leopard by its feet.’

It is said tattoos, once done, are for life. In this case, though, it was a whole lot longer. The experts say they were made with paint, partially concocted from the burned bits of plants, their soot or ashes which contained a high level of potassium. The drawings were pierced with a needle, and rubbed with a mixture of soot and fat.

WHAT RESEARCH ON HER BODY SHOWS

The experts say she died in her 20s, with the best guess at 25 to 28, and that this was 2,500 or more years ago, making her, for example, some five centuries older than Jesus Christ, and several hundred years the senior of Alexander the Great.

‘She was called ‘Princess’ by the media. We just call her ‘Devochka’, meaning ‘Girl’. She was 25-28 years old when she died,’ said Irina Salnikova, head of the Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences Museum of Archeology and Ethnography.

‘The reason for her death is unknown, because all her internal organs were removed before the mummifying. All we see is that there is no visible damage to her skull, or anything pointing to the unnatural character of her death.

‘Her body is curled, so we cant say for sure how tall she was. Some estimate her to be 1.62 metres, others say she could have been as tall as 1.68 metres. We could not establish when the young woman has had her tattoos made, at what age. The horses, found by her burial, were most likely first killed, and then buried with her.’

In 2010 an MRI scan was conducted on the mummy, the first time this had been done on ancient remains in Russia. The final results of exhaustive analytical work has still not been released.

But Andrei Letyagin, chairman of the MRI Center of the Siberian department of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said: ‘The cause of death remains unknown. I don’t believe that it will be possible to find an answer to this question because there’s no brain and no internal organs in the body.’

In all probability she did not die from injury. ‘Her skull is fully preserved, and so are the bones,’ he confirmed. DNA obtained from her remains is intriguing.

The Princess of Ukok is not related to any of the Asian races, the scientists are convinced. She is not related, evidently, to the present day inhabitants of Altai. Moreover, she had a European appearance, it has been claimed.

‘There was a moment of gross misunderstanding when a legend came about this mummy being a foremother of people of Altai,’ said Molodin.

‘The people of Pazyryk belonged to different ethnic group, in no way related to Altaians. Genetic studies showed that the Pazyryks were a part of Samoyedic family, with elements of Iranian-Caucasian substratum.’

So perhaps more Samoyedic than Scythian.

‘We tried to overcome the misunderstanding, but sadly it didn’t work.’

OBJECTIONS

Many locals in Altai were nervous from the start about the removal of remains from sacred burial mounds, known as kurgans, regardless of the value to science of doing such work.

In a land where the sway of shamans still holds, they believe the princess’s removal led immediately to bad consequences.

‘There are places here that it is considered a great sin to visit, even for our holy men. The energy and the spirits there are too dangerous,’ warned one local. ‘Every kurgan has its own spirit – there is both good and bad in them – and people here have suffered much misfortune since the Ice Princess was disturbed.’

It is nothing short of sacrilege to pour hot water on the remains of ancients who have survived in the permafrost for thousands of years, he said.

The ‘curse of the mummy’ even caused a crash of the helicopter carrying her remains away from Altai, some believe. Then in Novosibirsk, her body, preserved so well for so long, started to decompose.

Stories circulated that the princess had been stored in a freezer used to preserve cheese. Fungi began growing on the preserved flesh, it was claimed.

Whatever the truth, the scientists sought emergency help from the world-renowned Lenin embalming experts who worked on her remains for a year.

Back in Altai, many ills have been blamed on her removal: forest fires, high winds, illness, suicides and an upsurge in earthquakes in the Altai region.

Local woman, Olga Kurtugashova, said: ‘She may be a mummy but her soul survives, and they say a shaman communicated with her and she asked to go home. That’s what the people want, too.’

‘Our ancestors are buried in these mounds,’ insisted Rimma Erkinova, deputy director of the Gorno-Altaisk Republican National Museum as a war of words raged over the last decade. ‘There are sacred items there. The Altai people never disturb the repose of their ancestors. We shouldn’t have any more excavations until we’ve worked out a proper moral and ethical approach.’

Related Post

A shocking documentary proves that mermaids do exist

SHOCKING Revelation: Thuya, Mother of Queen Tiye, Was the Grandmother of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun—What Ancient Egyptian Secrets Did She Leave Behind?

Breaking News: Astonishing Discoveries at Karahan Tepe Confirm an Extraterrestrial Civilization is Hiding on Earth, and NO ONE Knows!

Breaking News: Researchers FINALLY Discover U.S. Navy Flight 19 After 75 Years Lost in the Bermuda Triangle!

NASA’s Secret Investigation: Uncovering the Astonishing Mystery of the UFO Crash on the Mountain!

Explosive UFO Docs LEAKED: Startling Proof That Aliens Ruled Ancient Egypt!