More than a decade ago while I was writing an article, an old story crossed my path again. It was when I came across the enigma of Tayos, which Erich von Däniken popularized in his book, ” The Gold of the Gods ” back in 1972, being one of his first best sellers. That work that catapulted him to universal fame would simultaneously uncover furious controversy, currently still alive. The inclusion of an intriguing color material, where von Däniken presented beautiful pieces, of unclassifiable historical origin, belonging to a Salesian museum in Ecuador, put the world on alert.

And the so-called Crespi Collection took your breath away, beginning from then on, its fame as one of the most amazing South American treasures.

I invite the reader to learn the details of one of the most striking stories in terms of mysteries.

The Rebel Salesian

“When I was studying at the San Ambrosio School, I had just fallen asleep and the Virgin showed me a scene: on the one hand the demon wanted to grab me and drag me; On the other hand, the Divine Redeemer, with the cross, showed me another path. Then I saw myself dressed as a priest with a beard, I went up to an old pulpit with a crowd of people around me eager to hear my word. The pulpit was not in a Church but in a cabin. I woke up immediately, some dormmates who were still awake heard my preaching and the next day they told me about it.” Father Carlos Crespi.

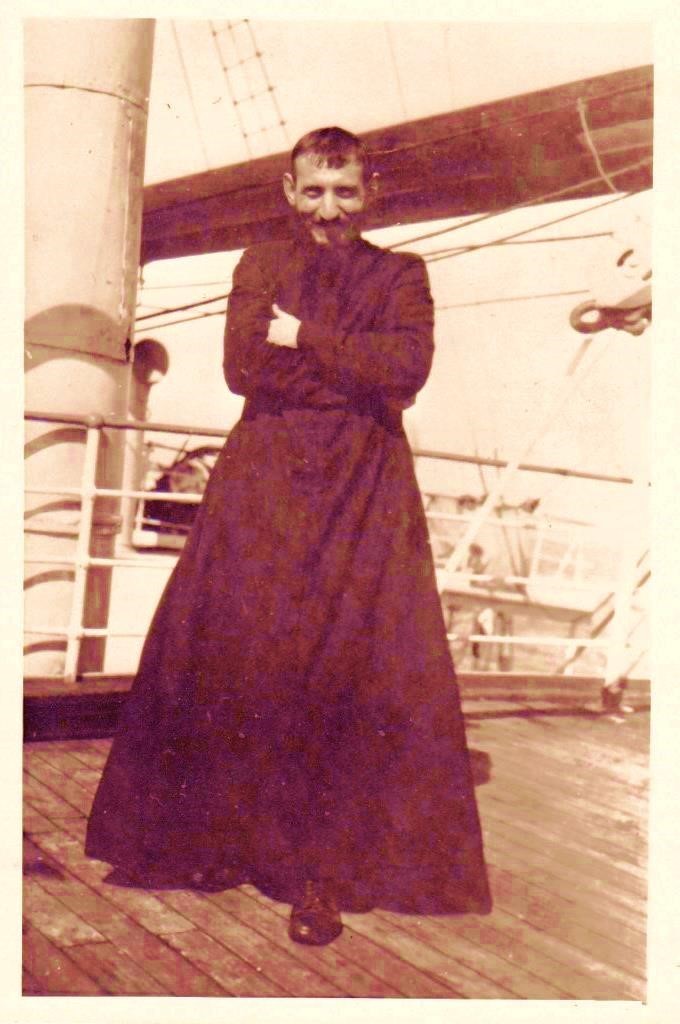

Early photograph of Carlos Crespi, portrayed in 1926. Courtesy: carlocrespi.org

Carlos Crespi Crocce was born on May 29, 1891 in Legnano, Milan (Italy). The son of a large family, at the age of 15 he asked to be incorporated as a novice at the Salesian College of Turin. During his formative years he learned philosophy, natural sciences, mathematics and music.

The Cornelio Merchán Tapia Institute, which from 1936 to 1962, was home to the Crespi Museum. Courtesy: carlocrespi.org

In 1923 he arrived with a contingent of Salesians in Ecuador, which would become his permanent residence. It is established in Cuenca, province of Azuay (southern east), establishing its base of operations in the María Auxiliadora Church. His contribution to the region is immense:

He built bridges, bridle paths, little schools for the settlers’ children and later also founded carpentry and mechanics workshops.

He brings electricity to forgotten places, and even takes time to venture into cinema, filming documentary films, dedicating one of his first productions to showing the Colorado Indians, ‘ The invincible Shuaras in the Upper Amazon ‘, 1927, which he screened in several cities in Ecuador as well as Europe, allowing him to raise money to continue his work.”

But this tireless priest had a hobby almost unknown to a large majority of Ecuadorians, Archaeology, which dated back to his time as a student at the University of Milan , before entering the Salesian Order . According to testimonies, Carlos Crespi began the organization of his famous Museum in 1931, although other voices speak of 1935. Possibly it was this last year, coinciding with the founding of the Cornelio Merchán Tapia Institute , in the city of Cuenca, where Crespi would carry out most of of his work, especially educational.

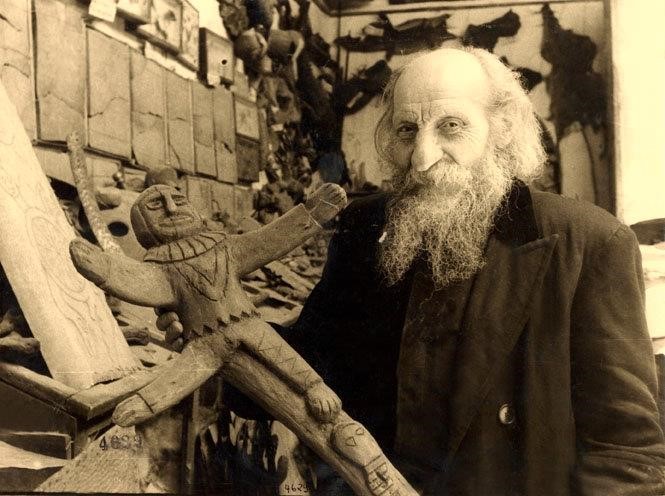

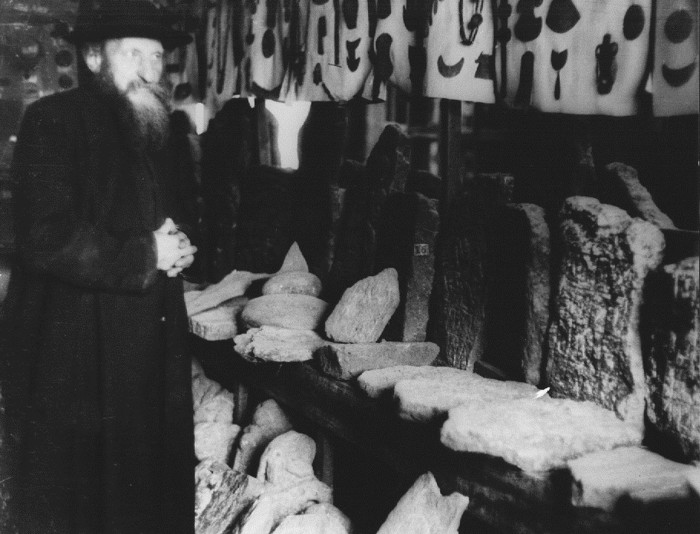

Snapshot of Crespi captured, contemplating with thoughtful eyes, his unclassifiable collection. Courtesy: carlocrespi.org

A chance discovery while excavations were being carried out to build the imposing Merchán Tapia Institute , triggered his desire to have a reservoir of archaeological material, which would take as inspiration the Egyptian Museum in Turin, one of the most important in Italy.

Thus, Crespi begins an ambitious collection, which has the indigenous community as one of its main suppliers. Although they won’t be the only ones. Other donations will come from local farmers, private collectors, artisans, and huaqueros, in addition to personal contributions from Crespi himself, translated into purchases, as well as finds made during explorations. In reality, Crespi took advantage of his archaeological push, in the face of official indifference, which had little interest in rescuing indigenous heritage. Slowly the collection came to life, growing by leaps and bounds. However, problems did not take long to arise, fueled by the lack of space, and the little time spent by Crespi due to his own clerical duties, which prevented better supervision of these pieces.

Enigmatic Crespi pieces, captured in the seventies. Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

Crespi begins a systematic accumulation, which will lack any concise classification and dating. In short, a serious study that seeks to provide detailed information about the objects. None of this happened. However, the Museum begins to receive attention, and becomes the local talk of the artifacts on display, incongruent with the traditional cultures referenced within Ecuador itself, as well as the rest of South America. Already around that time Crespi began to give shape to a personal idea, where an ancient pre-Columbian globalization would have reached great traffic in the past of America, with the Middle East, Asia and Africa being some of its main axes.

That a priest openly expressed these ideas was seen as a provocation, especially among local historians, where a communicated America interfered with a past of isolation. Other actors also expressed their annoyance, such as the Vatican itself, which began to become concerned at the audacity of one of its own. The reprisals did not take long to manifest themselves.

The strange fire at the Crespi Museum. Attacking the uncomfortable side of History

On July 19, 1962, a raging nighttime fire attacked the facilities of the enormous Cornelio Merchán Tapia Institute building, where Carlos Crespi had stored his Museum in three rooms. Ecuador was experiencing turbulent times politically, alarmed by the Cuban triumph and the growing tension with the United States.

Images of the fire that burned the beautiful building, Instituto Cornelio Marechán Tapia, in 1962. Was it the work of an attack? Courtesy: fotografiapatrimonial.gob.ec

Just months later the missile crisis would occur, which would take this animosity to its maximum. The truth is that Ecuador internally was affected by this situation, with a president, Carlos Julio Arosemena Monroy, who was later overthrown by a military junta. It is said that this uprising had the infiltration of the CIA, as the informant Philip Agee later denounced in his book, ” Inside the Company: CIA Diary “, published in 1975, and a book banned in Ecuador.

Within this context, the Ecuadorian Catholic Church exercised fierce anti-communism, which they saw as an exaltation of repudiated atheism, also practicing extreme conservatism. The Salesian Order, which had an active presence since the 18th century, received a hard blow in 1860 when it was expelled from Ecuador, due to political differences. However, in 1900 there was a triumphant return, winning a trial that allowed them to recover seized assets.

Its role in Ecuador aims to accentuate indigenous evangelization (which some see as a form of domination and covert colonization), receiving local support for its task. Taking these points into account, we can understand that the still remembered fire was caused in part by these detailed factors, but there are some data that introduce more tension. The Crespi Collection had begun to be a real nuisance, not only for the Vatican, but for other covert actors, perhaps annoyed by the emergence of this alternative history deployed by the restless Salesian.

Crespi holding famous Hindu style iron, engraved with 52 symbols. Without a doubt, one of the most iconic objects of the missing Museum. Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

Although the losses were considerable in terms of the building structure, the Crespi Collection suffered some consequences, but not as many as is usually reported, managing for the most part to survive the disaster. During the making of my book about Cueva de los Tayos. Underground Secrets of the Forgotten Worlds, 2016, I managed to locate a document of interest, penned by Crespi himself, resulting in a revealing letter, written a month after the incidents, and sent to Dr. Antonio Santiana, president of the Society of Friends of Archeology in Ecuador, testifying to the following:

The archaeological museum defended itself in a heroic way. The magnificent hall of coppers, of funerary tombstones with ancient writing, hundreds of pottery objects, in total 5,000 objects, was completely saved, this being in a reinforced concrete hall, the stone museum was also saved, almost everything and some monoliths of some quintals were broken after the fire: the last piece is well kept in a park and is already being rebuilt, thanks to the generous offer of Mr. Di Capúa, another museum has already been improvised and the thousands of intact stones will be listed for the 10th of August.

Conclusions: the great museum of pottery and gold was all saved, the great museum of artistic paintings and sculptures intact, the great museum of copper and select pottery also intact, the museum of paintings in the corridor was saved by 80%, some remaining to be patched very heavy monoliths, the entire orientalist museum was saved from the flames, but many birds were damaged by the water and quite a few birds stolen from a minga 3 days after the fire, the artistic paintings of little value were burned, I say of little value because in 25 years exhibitions in the Theater, as soon as I noticed a good painting I removed it from the corridors and kept it in a special deposit that remained intact.

But as we said, did anticlerical animosity alone cause the fatal fire, the work of communist activists, some say, or can we attribute the attempted destruction to something less visible? And we return to the same question: had the Museum become an affront to certain immovable historical interests? Long before these events, occasional robberies had intensified. We can think of them as the work of private collectors, eager to get hold of this apocryphal material.

Other reports collected by this author suggest the existence of a plot on the part of the Salesians themselves, although this may sound incongruous. Ruling out this hypothesis, who and why? Of course uncomfortable questions. The truth is that after these events, Carlos Crespi would take precautions regarding the safeguarding of his unclassifiable treasure, leading to depositing the most expensive evidence (those pieces made of valuable metals, such as gold and other precious metals) in a box. strong banks. Duplicates would also be born, which would confuse the experts, leading them to baptize those pieces, “as simple trinkets.” They didn’t know how wrong they were.

Atlantean vestiges in the Andes

After the intentional burning, the Crespi Museum slowly resumed its activities, supported by a rapid reconstruction of the main facilities. The new museum would be housed in the basement of the María Auxiliadora Church. A series of iconic visits by foreign scholars, interested in contemplating the collection in situ, will leave some interesting reflections. The first to take center stage was Pino Turolla. Of Yugoslav origin, Turolla (1922-1984) was of noble descent and had a noble title on his resume. He was a combatant in the Second World War alongside English troops. After the war, he moved to Miami (USA), where he dedicated himself to underwater exploration. Turolla believed in the existence of the lost Atlantis, and searched for clues to this disappeared civilization. He focused his search on Bimini, and then moved the operation center to the Andes.

By 1965 he began working in the Amazon regions of Ecuador and Peru, exploring hitherto inaccessible places. On one of his tours, he was informed about the Crespi Collection and went to visit it. Shortly after, Turolla published a book, ” Beyond the Andes: my search for a pre-Inca civilization ” (1980), which in one of its chapters portrayed the results of his meeting with the priest. Turolla simply did not believe in Crespi, and the disorder of the collection led him to think that the priest was not in his right mind.

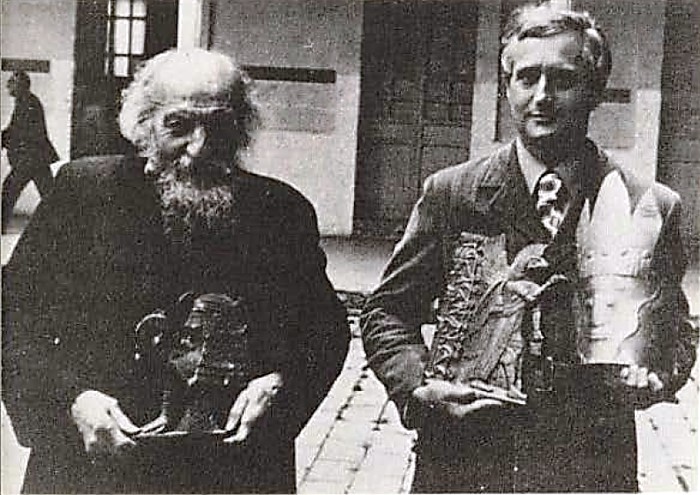

The Italian count Pino Turolla, who left a very negative report about the Crespi Museum, during his visit in the 1960s. Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

Shortly after, a major celebrity would arrive, Dr. Joseph Manson Valentine, (1902-1994), marine biologist and discoverer of the famous Bimini Highway, a supposed Atlantean vestige back in 1968. Valentine, who would later achieve repercussion through the dissemination From the books of his friend Charles Berlitz, who popularized his findings, he paid a visit to the Crespi Museum, believing he saw vestiges of the disappeared Atlantis in the collection. He left his impressions in a work Men Of Good Faith. The Carlos Crespi Collection , Cuenca, Ecuador, which was unveiled in the prestigious New World Antiquity .

Published in the Jan-Feb 1968 issue, a few months later in September of that same year, the world would be amazed by its announcement of an Atlantean highway, under the waters of the Caribbean. Manson Valentine would be continued by Richard Wingate, (1933-2011), who at his request would meet with Carlos Crespi. Qualified as an expert mineralogist, explorer, knowledge in underwater archaeology, this last slogan would lead him to the search for the lost continent revealed by Plato, in his famous dialogues. Wingate would allege discoveries in the Bahamas, where he said he detected buildings under the sea. His first visit to the Museum took place in the seventies, which a decade later he would portray in his famous book ” The Lost Outpost of Atlantis “, 1980. There he would leave written and photographic impressions of what he observed, of an indelible nature.

I was amazed by their large collection of artifacts. There were a few series, of what appeared to be shining golden suits of Inca full dress armor, along with Chaldean-style gold helmets, and gold plates inscribed with a linear alphabet, later identified as proto-Phoenician by Professor Barry. Fell. Piled haphazardly on the floor are red copper shields, lots of ceramics, sheets, and rolls of silver-colored metal, others plated with gold, strange gears and wheels, peculiar uncoiled brass tubes. Scattered among the gold, plaques representing dinosaurs. “King Midas’ treasure piled up in the jungle, I thought.”

The remembered visit of the North American scholar to the Crespi Museum in the seventies, Richard Wingate, one of the great Atlanticologists of his time. Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

Interest in what he observed led Wingate to extend his Ecuadorian stay, making him visit the Museum three more times. As crucial information, in addition to the attack that the collection suffered in 1962, the researcher echoes another fire, which would have been recorded in 1974, without taking into account the occasional thefts.

Although at the time, Crespi minimized the damage to his collection due to these incidents, he admitted to Wingate that part of the treasures were affected, which led to a reduction in their value, showing pronounced deterioration. He also pointed out that as a way to preserve the heritage, the most important pieces were set aside, and have since been kept in the safe of a bank. As a result, a duplication of the original evidence occurred, revealing the subsequent confusion.

About the origins of the treasure, Wingate records the following:

When Father Crespi and his indigenous excavators talk about the places where their artifacts are found, they describe giant pyramids, temples, and immense desert cities. Also fantastic sacred tunnels and caves. The cities, they say, still shine with a bluish light. The tunnels are reportedly large enough to drive a locomotive inside. Entrances and walls, which according to the natives, are as smooth as glass. The Tayos, according to Crespi, would also be part of the game.”

Huge strips of aluminum that Richard Wingate located inside the Museum. Atlantean evidence? Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

In his final conclusions, he risks the theory that many of the treasures would be related to the Atlantean legacy, even being able to observe remains of advanced technology. These deductions derived their sources from theosophical writings, as well as from the prophetic readings bequeathed by Edgar Cayce. One of the most striking examples in his book was the portrait of extensive strips of metal, baptized as aluminum snakes, never before seen in other records of the collection, rescued from the jungle thanks to indigenous intervention. According to Wingate, this material found its relationship in an old treatise by Annie Bessant and CW Leadbetaer, (1913) « The Man. Where and how did it come? Where is it going? ».

Wingate narrates:

At the time to which our information refers, the inhabitants of Peru did not know our art of gilding, but they were extremely skilled in forging wide, thin sheets of metal, so it was not unusual for the walls of the temples to be completely covered with plates of gold and silver, whose thickness usually measured six millimeters and were molded to the delicate reliefs of the stone, as if they had been made of paper, so that, from our modern point of view, a temple was frequently a repository of unspeakable riches. ”.

These visions of a disappeared continent linked to the Crespi treasure will also be shared by János Móricz, who will link his own discoveries in Cueva de los Tayos, with the Atlantean thesis, as he revealed in an old interview from 1978, sharing the following:

After multiple observations and incessant research related to the tunnel system, I have come to the conclusion that an underground world exists in the bowels of the Andes mountain range. This system has, in fact, many different inputs. Some of them are obstructed, others are open but there are always many access routes. Somewhere down there are objects and relics from the distant past. I am talking about many years, thousands of years, from a time long before the existence of the giants. There are war chariots in certain places, remains of very ancient cultures and objects that vividly remind us of what we know about Atlantis.”

Carlos Crespi, apostle of the poor. The saint of Cuenca. Courtesy: carlocrespi.org

In my extensive research of almost a decade, I would find a suggestive clue about the origin of some pieces from the controversial Crespi Museum, giving me some surprises. Let’s see .

The Shadow of Lemuria

It happened when in 2009 I found the site Ancient Tresaures Hunter , by American scholar Steve Shaffer, where I found never-before-seen pieces from the Crespi collection. This incredible photographic material showed a series of objects, whose engravings resembled Oceanian cultures, accompanied by the following legend:

The photos shown here are part of a large collection from Cuenca, Ecuador collected by local Indians and brought to Father Crespi. The priest had a room full of gold objects, of all shapes and types, including; statues, solar discs, glasses, pots and plates, and even creatures modeled and covered in gold leaf. Many of the artifacts came from the caves and ruins of an ancient temple within the parish area. In Paute, workers who were building a road accidentally discovered a large cave shrine. The bulldozer cut into the side of the hill, opening a hole in the cave. A man was sent to investigate inside, but he did not come out. Another man was sent away, and he did not return either. The priest was then sought out, who recognized the problem immediately, instructing the workers to make another hole, in order to ventilate the cave for a day. After that the next day, the priest and some of the workers entered the cave, looking for the two missing men.

Disturbing engravings that were portrayed by the famous ufologist, Wendelle Stevens. Remains of Lemuria? Personal Archive / Débora Goldstern

To his surprise, he found himself inside the cave, with a shrine housing a treasure from some long-lost civilization. He saw a series of giant Tikis, carved from guayacan. Large clay pots, and some clay storage bottles. Under many inches, almost a foot deep in some spots of bat guano, the priest, found tablets of solid gold, averaging about eight to twelve inches long, by six to nine inches wide, engraved in deep relief, up to three quarters of an inch thick. These plates appeared to be sand-cast pieces, which had probably had a fine glossy finish rubbed on one side with guaiac sticks, thus giving them an almost jewelry-like finish on the front. The back of the pieces had a metal gold production not finished or coated in any way. These gold plates were valued at between thirty to fifty pounds, depending on their size. In some of these plates, mostly made of gold and silver, precious stones such as ruby, sapphire and emeralds were added, introducing them into small cavities within the metal. The scenes depicted on these plates seemed to allude to an unknown civilization, probably peaceful in origin. The style and arrangement of the furniture, clothing used, and the hairstyles shown on the human figures did not conform to any society known to them.”

According to evidence, the discovery took place in the canton of Paute, located forty kilometers from Cuenca, where archeology locates important settlements of the Cañaris ethnic group. Beyond these data, reality shows that the findings have little to do with the cultures of the area, ignoring their real origin . Buried treasure? But by whom? To learn a little more about the story, I contacted Shaffer, revealing that those shots were provided to him by Colonel Wendelle Stevens, who visited the Museum in the 1970s.

Upon hearing Stevens’ name, a cascade of images came to mind, starting with the Swiss contactee Billy Meier, whom this USAF officer sponsored, later becoming a renowned ufologist. His passion for the UFO topic was well known, which led him to travel halfway around the world to capture and document the phenomenon. However, his adventures through the Ecuadorian jungle received little press, although some information was already circulating.

In 2013, ” Hitler’s Treasure of the Ancient World ” was published, a post-mortem work, where Stevens talks about his research in Jíbara lands. He says that his interest began with the search for Atahualpa’s treasure, which reminds me of János Móricz, dedicating himself for three long years, 1972-1975, to trying to locate the elusive Inca cargo. It was in this period that Stevens became involved with the Crespi Museum , later becoming one of the few researchers to see the lost collection in situ. His book, however, opts for the Nazi issue, which he believed was linked to certain management of the Museum, based on his observations about the art gallery also housed by Crespi, which he assumed were original legacies stolen by the Nazis during the Second War. and later transferred to Ecuador.

This hypothesis contradicted the opinion of experts, who alleged that these works were imitations made by Quito artists. Another audacity suggested, according to Wendelle, Crespi as an escaped Hitler, and with surgery included, which does not merit any comment.

Beyond these curiosities, the truth is that the collection immortalized by Stevens showed original pieces, far from the junk reviled by critics. In some of these snapshots, we could see real slides from the past, assembled in triptych shapes, which were later dismantled, becoming unique plaquettes. These pieces personally convey to me a certain connotation that leads me to think if the lost Lemuria, another continent still invisible in history, could be part of this South American discovery. Although at the moment it is just a sketchy track.

Carlos Crespi in the midst of his priestly work, his enigma continues. Courtesy: adb.ec

Requiem for the Crespi Collection

In 1972 the world was shocked by the publication of ” The Gold of the Gods “, an iconic book by Erich von Däniken. Its history, disclosed at that time, attracted even more attention to the Crespi Museum and its treasures. More illustrious visits followed, and amazement continued to reign, but in 1982 with the death of Carlos Crespi, his legacy entered a cone of shadows, beginning a long ordeal over the fate of the pieces, whose trace begins to fade. End announced for some, or omens fulfilled, it doesn’t matter. The truth is that since then, knowing the whereabouts of those pieces immortalized in so many photographs has become a detective task. The first known reports spoke of an important sale by the Salesians, whose first recipient was the Central Bank of Ecuador, who paid a large sum to obtain part of that collection.

Incredibly, this event took place two years before Crespi’s death, 1980. Some rumors indicate that the priest resigned himself to his fate, already overwhelmed at that time by a mental illness, which was slowly taking away his lucidity in his actions. The great disorder of the collection determined drastic actions, such as the discarding of pieces classified as not important, which ended up becoming scrap metal. Other artifacts were melted down.

But more actors came into play, private collectors, eager to get their hands on the valuable loot. Although many scholars held to the script of skillful forgeries by local artisans, in 1968 the collection was examined by a renowned Ecuadorian archaeologist, priest Pedro Porras Garcés, who was commissioned with the task of determining its validity.

An old image of the Crespi Museum, when it was still working. Courtesy: carlocrespi.org

On the matter I would express:

The stone steles or tablets with inscriptions do not in their entirety look like vulgar fakes. It is worth noting the percentage of authentic objects, once separated from the extremely interesting fakes, given the rarity and quality of some specimens.”

It is worth highlighting this attempt to support the legality of the Museum, it had a previous precedent that dates back to 1965, when a letter was sent to the OAS (Organization of American States), inviting experts to curate the collection. The letter of intent was written by the Ecuadorian historian, Tomás Vega Toral, where in one of his paragraphs he writes:

These finds are practically buried and go almost unnoticed, as can be seen when visiting the museum. If the experts’ report were positive, we could see if it is possible to provide financial help to build, perhaps not a building, but at least a large hall, in the Salesian House itself, in which you can organize, according to your criteria. technical classification, the thousands of precious archaeological objects.”

Announcement made by the authorities of Ecuador, with plans for the reestablishment of the missing Crespi Collection. Estimated date 2020. Courtesy: twitter.com/inpcecuador

As we see, there was a genuine interest in that collection on the part of the authorities, or those interested in its conservation. However, Crespi’s death buried any subsequent attempt to continue investigations into the material. It was very important to observe how in recent decades those scholars who in situ tried to find the whereabouts of the lost collection, came up against a wall of silence .

Neither the Salesians nor the authorities of the Central Bank seemed to have any desire to satisfy the questions that arose after Crespi’s departure, and subsequent dismemberment of his precious treasure. Only in recent years have some leaks taken shape.

In my personal search, I learned from first source how a shipment of Crespì pieces left Ecuador to be exhibited in a European exhibition at the beginning of 2000, authorized by the Central Bank, with little interest, according to the confession witness, in retaining that material. Other shocking testimony made me participate in a chilling story, Crespi pieces used by the Salesians as repair material. And the stories continue, but in order not to discourage the reader, I will say that there is currently a serious project underway, which seeks to finally restore the surviving collection to its splendor. 2020 is mentioned as a key year. Whoever writes expects a miracle . So far .

Conclusion

Carlos Crespi Croci Hero or Villain?

Although Carlos Crespi Croci is considered almost a saint for his actions, and celebrated as the creator of that wonderful museum, which once had him as its protagonist, it is fair to say his figure is under review within some circles in Ecuador, propelled by some indigenous groups. One of the main accusations against Crespi is his appropriation of valuable material from the Shuar ethnic group, which, with the excuse of an exhibition in Turin, Italy, was never returned to him. To understand this malaise we have to go back to 1923, when Crespi made his first forays into the jungle that had the regions of Méndez, Gualiquiza and Indanza as territories where he began his evangelizing task.

During this period Crespi collected documentary, ethnographic, and photographic information from the areas visited. The objective of this apparent interest is to accumulate material for an International Missionary Exhibition, which the Vatican planned in 1924, based in Turin, Italy. It was there that Crespi is said to have taken certain archaeological material given by the Shuaras, or perhaps deceived, a loan that would never return to its legitimate owners.

It is important to note that in Turin, one of the most important Salesian headquarters of the powerful congregation is located. But there are more reports on this point. And here I appeal to the contribution made by an independent researcher, Michael Palomino, who in 2012 narrated how a Salesian priest revealed to him at his insistence to obtain data on the missing Crespi collection, that his order had transferred the most precious pieces from the Crespi Museum to Turin , since the Central Bank of Ecuador received artifacts of less value in its acquisition.

At other points in his speech, Palomino makes more explosive allegations, implicating the then mayor of Cuenca, and even the Ministry of Culture of Ecuador itself, as accomplices in these corrupt operations. Was this the real mission of Carlos Crespi during his Ecuadorian stay, who, protected under the Vatican service, searched for vestiges of a prehistoric American history yet to be written? To be continue .

Photograph depicting the International Missionary Exposition, held between 1924-26. Turin, Italy. Here the indigenous room, in the foreground, the founder of the Salesian order, Don Bosco. Courtesy: magazineprocesses.ec

Bibliography

Books

- Agge, P. Inside the Company: CIADiary. New York: Stonehill Publishing Company, 1975.

- Chatelain, M. (1984). The time and the space. Barcelona, Spain: Plaza & Janés.

- Daniken, E. (1976). The Message of the Gods. Barcelona, Spain: Martínez Roca.

- Daniken, E. (1978). The Response of the Gods. Barcelona, Spain: Martínez Roca.

- Daniken, E. (2010). History Lies. Madrid, Spain: Edaf.

- Däniken, E.. (1974). The Gold of the Gods: Barcelona, Spain: Martínez Roca.

- Fell, B. America BC The First Colonizers of the New World. (1983). DF, Mexico: Diana.

- Goldstern, D. Cueva de los Tayos, Underground Secrets of the Forgotten Worlds. Spain: Corona Borealis, 2016.

- Turolla, P. (1980). Beyond the Andes. My search for the origins of a pre-Inca civilization. New York, USA: Hapercollins.

- Wingate, R. (1980). Lost Outpost of Atlantis. New York, USA: Everest House.

Sites

- 13thfloor

the-real-atlantis-the-underwater-world-of-bimini-road.

http://www.the13thfloor.tv/2017/06/14/the-real-atlantis-the-underwater-world-of-bimini-road/ - Arqueoweb

Executioner Steer; Vera Cabrera.

Of archeologies and fantasies: the myth of Father Crespi and its influence on “archaeology”. Ecuadorian.

https://webs.ucm.es/info/arqueoweb/pdf/18/05_NovilloVera.pdf - Diario El Tiempo

Crespi Collection, between the reserve and the heritage.

https://www.eltiempo.com.ec/noticias/cultura/7/coleccion-crespi-reserva-patrimonio - Heritage Photography

Cornelio Marechan School

http://fotografiapatrimonial.gob.ec/web/es/galeria/element/14257 - Ecuadorian History Magazine

Pagnotta, C.

The Vatican Missionary Exhibition of 1925, the Salesian missionaries and the representation of the Ecuadorian East.

http://repositorio.uasb.edu.ec/bitstream/10644/6322/1/04-ES-Pagnotta.pdf - ONLUS

Father Carlo Crespi.

http://carlocrespi.org/don-carlo-missionario-2/ - Palomino, M.

Cuenca: Father Crespi

https://www.am-sur.com/am-sur/ecuador/Cuenca/padre-Crespi-cronologia-ESP.html - We Are the Mutants

Roberts, K. Everything-is-wrong-a-history-of-the-bermuda-triangle-legend.

https://wearethemutants.com/2016/12/05/everything-is-wrong-a-history-of-the-bermuda-triangle-legend/

We have something to tell you: Visit us on Facebook. Join the discussion in our community on Telegram. And if you can, support our work by buying us a coffee. We appreciate it!