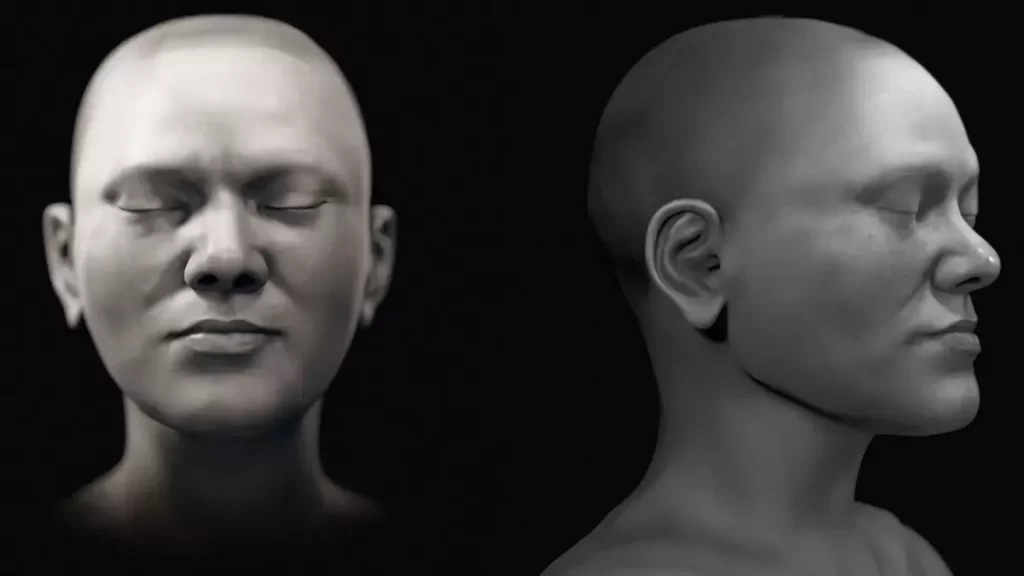

A facial approximation of the Zlatý kůň woman offers a glimpse of what she may have looked like 45,000 years ago.

In 1950, archaeologists discovered a severed skull buried deep inside a cave system in Czechia (the Czech Republic). Because the skull was split in half, researchers concluded that the skeletal remains were of two separate individuals.

However, through genome sequencing done decades later, scientists concluded that the skull actually belonged to a single person: a woman who lived 45,000 years ago.

Researchers named her the Zlatý kůň woman, or “golden horse” in Czech, in a nod to a hill above the cave system.

Further analysis of her DNA revealed that her genome carried roughly 3% Neanderthal ancestry, that she was part of a population of early modern humans who likely mated with Neanderthals and that her genome was the oldest modern human genome ever to be sequenced.

Although much has been learned about the woman’s genetics, little is known about what she may have looked like. But now, a new online paper published July 18 offers new insight into her possible appearance in the form of a facial approximation.

A black-and-white version of the facial approximation.

A black-and-white version of the facial approximation.

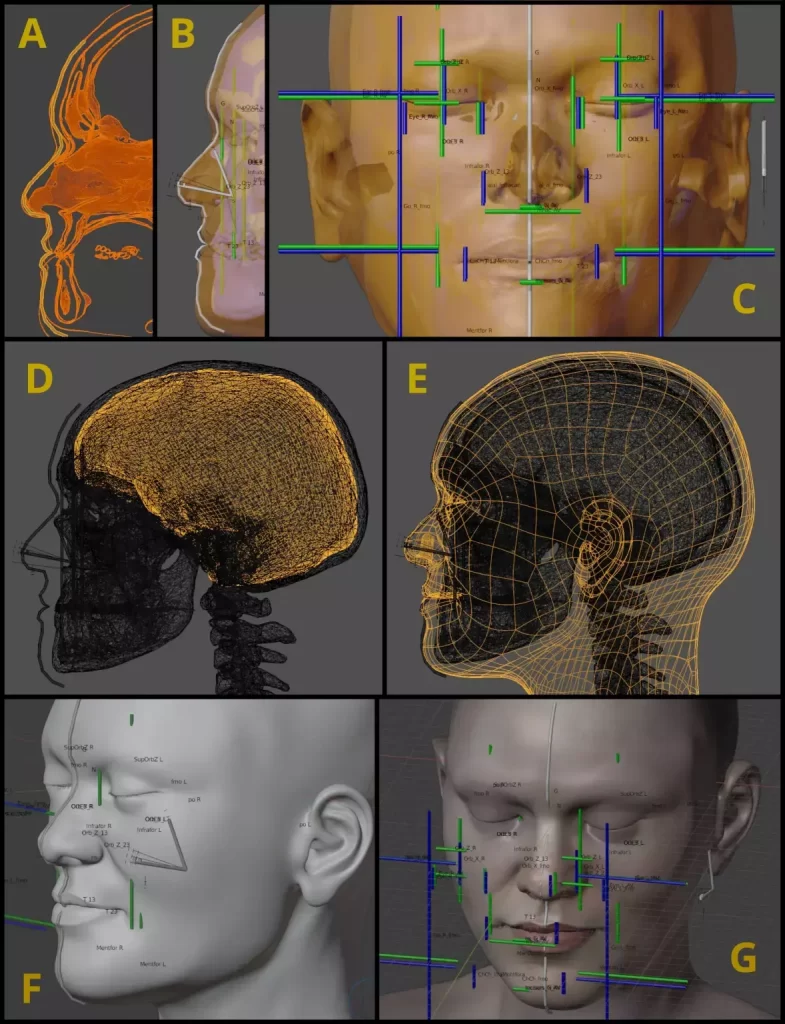

To create the woman’s likeness, researchers used data collected from several existing computed tomography (CT) scans of her skull that are part of an online database.

However, like the archaeologists who unearthed her remains more than 70 years ago, they discovered that chunks of the skull were missing, including a large portion of the left side of her face.

“An interesting piece of information about the skull is that it was gnawed by an animal after her death,” study co-author Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, told Live Science in an email. “This animal could have been a wolf or a hyena ([both were] present in the fauna at that time).”

To replace the missing portions, Moraes and his team utilized statistical data compiled in 2018 by researchers who created a reconstruction of the skull. They also consulted two CT scans — of a modern-day woman and man — as they created the digital face.

“What most caught our attention was the robustness of the structure [of the face], especially the mandible [lower jaw],” Moraes said. “When [archaeologists] found the skull, the first experts who analyzed it thought it was a man and it’s easy to understand why. In addition to the skull having characteristics that are very compatible with the male sex of current populations,” which included a “robust” jaw.

“We see that the jaw structure of Zlatý kůň tends to be more compatible with Neanderthals,” he added.

A strong jawline wasn’t the only feature that captured the researchers’ attention. They also found that the woman’s endocranial volume, the cavity where the brain sits, was larger than those of the modern individuals in the database.

However, Moraes attributes this factor to “a greater structural affinity between Zlatý kůň and Neanderthals than between her and modern humans,” he said.

“Once we had the basic face, we generated more objective and scientific images, without coloring (in grayscale), with eyes closed and without hair,” Moraes said. “Later, we created a speculative version with pigmented skin, open eyes, fur and hair. The objective of the second is to provide a more understandable face for the general population.”

The result is a lifelike image of a woman with dark, curly hair and brown eyes.

“We looked for elements that could compose the visual structure of the face only at a speculative level since no data was provided on what would be the color of the skin, hair and eyes,” Moraes said.

The woman’s nine-piece skull is under the care of the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum in Prague, and the researchers didn’t have access to the bones for their facial experiment.

The woman’s nine-piece skull is under the care of the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum in Prague, and the researchers didn’t have access to the bones for their facial experiment.

Cosimo Posth, an archaeologist who has studied Zlatý kůň extensively but wasn’t involved in the study, confirmed that much about this woman remains a mystery.

“The genetic data from Zlatý kůň I have worked on cannot tell us much about her facial characteristics,” Posth, an archaeology professor at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told Live Science in an email.

“In my opinion, morphological data can provide a reasonable idea of what the shape of her head and face might have been but not an accurate representation of her soft tissues.”