Among the duties of any Egyptian monarch was the construction of monumental building projects to honor the gods and preserve the memory of their reigns for eternity. These building projects were not just some grandiose gesture on the part of the king to appease the ego but were central to the foundation and development of a unified state. Building projects ensured work for the peasant farmers during the period of the Nile’s inundation, encouraged unity through a collective effort, pride in one’s contribution to the project, and provided opportunities for the expression of ma’at (harmony/balance), the central value of the culture, through communal – and national – effort.

Contrary to the view so often held, the great monuments of Egypt were not built by Hebrew slaves nor by slave labor of any kind. Skilled and unskilled Egyptian workers built the palaces, temples, pyramids, monuments, and raised the obelisks as paid workers. From the period of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) through the New Kingdom (c. 1570 – c. 1069 BCE) and, to a lesser extent, from the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525) through the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) the great rulers of Egypt created some of the most impressive cities, temples, and monuments in the world and these were all created by collective Egyptian effort. Egyptologist Steven Snape, commenting on these projects, writes:

The movement of large quantities of building stone – to say nothing of massive monoliths – from their quarries to distant building sites allowed the emergence of Egypt as a state that found expression through monumental construction. (97)

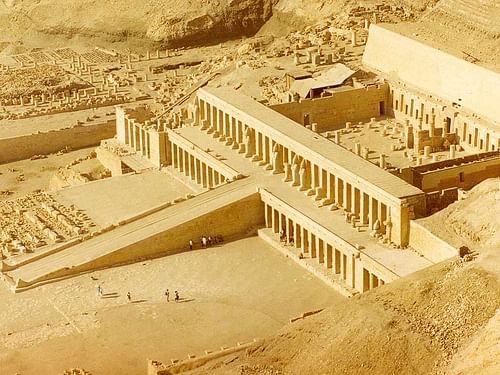

There are many examples of these great monuments and temples throughout Egypt from the pyramid complex at Giza in the north to the temple at Karnak in the south. Among these, the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) at Deir el-Bahri stands out as one of the most impressive.

Temple of Hatshepsut, Aerial View

N/A (CC BY)

The building was modeled after the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE), the great Theban prince who founded the 11th Dynasty and initiated the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). Mentuhotep II was considered a ‘second Menes’ by his contemporaries, a reference to the legendary king of the First Dynasty of Egypt, and he continued to be venerated highly throughout the rest of Egypt’s history. The temple of Mentuhotep II was built during his reign across the river from Thebes at Deir el-Bahri, the first structure to be raised there. It was a completely innovative concept in that it would serve as both tomb and temple.

The king would not actually be buried in the complex but in a tomb cut into the rock of the cliffs behind it. The entire structure was designed to blend organically with the surrounding landscape and the towering cliffs and was the most striking tomb complex raised in Upper Egypt and the most elaborate created since the Old Kingdom.

Hatshepsut, an admirer of Mentuhotep II’s temple had her own designed to mirror it but on a much grander scale and, just in case anyone should miss the comparison, ordered it built right next to the older temple. Hatshepsut was always keenly aware of ways in which to elevate her public image and immortalize her name; the mortuary temple achieved both ends.

It would be an homage to the ‘second Menes’ but, more importantly, link Hatshepsut to the grandeur of the past while, at the same time, surpassing previous monumental works in every respect. As a woman in a traditionally male position of power, Hatshepsut understood she needed to establish her authority and the legitimacy of her reign in much more obvious ways that her predecessors and the scale and elegance of her temple is evidence of this.

Hatshepsut’s Reign

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) by his Great Wife Ahmose. Thutmose I also fathered Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) by his secondary wife Mutnofret. In keeping with Egyptian royal tradition, Thutmose II was married to Hatshepsut at some point before she was 20 years old. During this same time, Hatshepsut was elevated to the position of God’s Wife of Amun, the highest honor a woman could attain in Egypt after the position of queen and one which would become increasingly political and important.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter, Neferu-Ra, while Thutmose II fathered a son with his lesser wife Isis. This son was Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) who was named his father’s successor. Thutmose II died while Thutmose III was still a child and so Hatshepsut became regent, controlling the affairs of state until he came of age. In the seventh year of her regency, though, she broke with tradition and had herself crowned pharaoh of Egypt.

Portrait of Queen Hatshepsut

Rob Koopman (CC BY-SA)

Her reign was one of the most prosperous and peaceful in Egypt’s history. There is evidence that she commissioned military expeditions early on and she certainly kept the army at peak efficiency but, for the most part, her time as pharaoh is characterized by successful trade, a booming economy, and her many public works projects which employed laborers from across the nation.

Her expedition to Punt seems to have been legendary and was certainly the accomplishment she was most proud of, but it also seems that all of her trade initiatives were equally successful and she was able to employ an entire nation in building her monuments. These works were so beautiful and so finely crafted that they would be claimed by later kings as their own.

The Temple Design & Layout

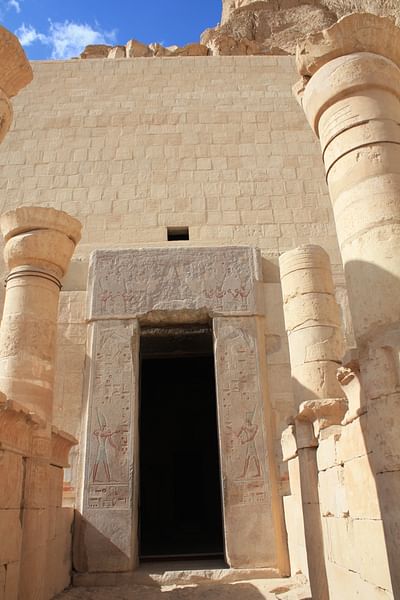

She commissioned her mortuary temple at some point soon after coming to power in 1479 BCE and had it designed to tell the story of her life and reign and surpass any other in elegance and grandeur. The temple was designed by Hatshepsut’s steward and confidante Senenmut, who was also tutor to Neferu-Ra and, possibly, Hatshepsut’s lover. Senenmut modeled it carefully on that of Mentuhotep II but took every aspect of the earlier building and made it larger, longer, and more elaborate. Mentuhotep II’s temple featured a large stone ramp from the first courtyard to the second level; Hatshepsut’s second level was reached by a much longer and even more elaborate ramp one reached by passing through lush gardens and an elaborate entrance pylon flanked by towering obelisks.

Walking through the first courtyard (ground level), one could go directly through the archways on either side (which led down alleys to small ramps up to the second level) or stroll up the central ramp, whose entrance was flanked by statues of lions. On the second level, there were two reflecting pools and sphinxes lining the pathway to another ramp which brought a visitor up to the third level.

Senemut, kneeling fugure

A.K. (Copyright)

The first, second, and third levels of the temple all featured colonnade and elaborate reliefs, paintings, and statuary. The second courtyard would house the tomb of Senenmut to the right of the ramp leading up to the third level; an appropriately opulent tomb placed beneath the second courtyard with no outward features in order to preserve symmetry. All three levels exemplified the traditional Egyptian value of symmetry and, as there was no structure to the left of the ramp, there could be no apparent tomb on its right.

Love History?

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

On the right side of the ramp leading to the third level was the Birth Colonnade, and on the left the Punt Colonnade. The Birth Colonnade told the story of Hatshepsut’s divine creation with Amun as her true father. Hatshepsut had the night of her conception inscribed on the walls relating how the god came to mate with her mother:

He [Amun] in the incarnation of the Majesty of her husband, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt [Thutmose I] found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. She awoke at the divine fragrance and turned towards his Majesty. He went to her immediately, he was aroused by her, and he imposed his desire upon her. He allowed her to see him in his form of a god and she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty after he had come before her. His love passed into her body. The palace was flooded with divine fragrance. (van de Mieroop, 173)

As the daughter of the most powerful and popular god in Egypt at the time, Hatshepsut was claiming for herself special privilege to rule the country as a man would. She established her special relationship with Amun early on, possibly before taking the throne, in order to neutralize criticism of her reign on account of her gender.

Birth Colonnade, Hatshepsut’s Temple

Jorge Láscar (CC BY)

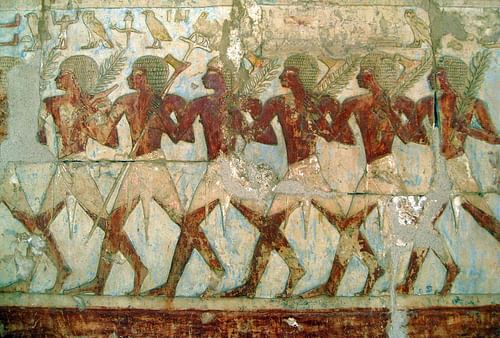

The Punt Colonnade related her glorious expedition to the mysterious ‘land of the gods’ which the Egyptians had not visited in centuries. Her ability to launch such an expedition is testimony to the wealth of the country under her rule and also her ambition in reviving the traditions and glory of the past. Punt was known to the Egyptians since the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) but either the route had been forgotten or Hatshepsut’s more recent predecessors did not consider an expedition worth their time. Hatshepsut describes how her people set out on the trip, their warm reception in Punt, and makes a detailed list of the many luxury goods brought back to Egypt:

The loading of the ships very heavily with marvels of the country of Punt; all goodly fragrant woods of God’s Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, Khesyt wood, with Ihmut-incense, sonter-incense, eye cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther. Never was brought the like of this for any king who has been since the beginning. (Lewis, 116)

At either end of the second level colonnade were two temples: The Temple of Anubis to the north and The Temple of Hathor to the south. As a woman in a position of power, Hatshepsut had a special relationship with the goddess Hathor and invoked her often. A temple to Anubis, the guardian and guide to the dead, was a common feature of any mortuary complex; one would not wish to slight the god who was responsible for leading one’s soul from the tomb to the afterlife.

The ramp to the third level, centered perfectly between the Birth and Punt colonnades, brought a visitor up to another colonnade, lined with statues, and the three most significant structures: the Royal Cult Chapel, Solar Cult Chapel, and the Sanctuary of Amun. The whole temple complex was built into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahri and the Sanctuary of Amun – the most sacred area of the site – was cut from the cliff itself. The Royal Cult Chapel and Solar Cult Chapel both depicted scenes of the royal family making offerings to the gods. Amun-Ra, the composite creator/sun god, is featured prominently in the Solar Cult Chapel with Hatshepsut and her immediate family kneeling before him in honor.

Desecration & Erasure from History

Throughout Hatshepsut’s reign, Thutmose III had not been idling at court but was leading the armies of Egypt on successful campaigns of conquest. Hatshepsut had given him supreme command of the military, and he did not disappoint her. Thutmose III is considered one of the greatest military leaders in the history of ancient Egypt and the most consistently successful in the period of the New Kingdom.

Thutmose III had all evidence of her reign destroyed from all public monuments but he left relatively untouched the story of her divine birth & expedition to Punt inside her mortuary temple.

In c. 1457 BCE Thutmose III led his armies to victory at the Battle of Megiddo, a campaign possibly anticipated and prepared for by Hatshepsut, and afterwards her name disappears from the historical record. Thutmose III had all evidence of her reign destroyed by erasing her name and having her image cut from all public monuments. He then backdated his reign to the death of his father and Hatshepsut’s accomplishments as pharaoh were ascribed to him. Senenmut and Neferu-Ra were dead by this time, and it seems anyone else who was personally loyal to Hatshepsut lacked the power or inclination to challenge Thutmose III’s policy regarding his step-mother’s memory.

To erase one’s name on earth was to condemn that person to non-existence. In ancient Egyptian belief, one needed to be remembered in order to continue one’s eternal journey in the afterlife. Although Thutmose III seems to have ordered this extreme measure, there is no evidence of any enmity between him and his step-mother, and significantly, he left relatively untouched the story of her divine birth and expedition to Punt inside her mortuary temple; only public mention of her was erased. This would indicate that he did not harbor Hatshepsut any ill will personally but was attempting to eradicate any overt evidence of a strong female pharaoh.

The monarch of Egypt was traditionally male, in keeping with the legendary first king of Egypt, the god Osiris. Although no one knows for sure why Thutmose III chose to remove his step-mother from history, it is probably because she broke with the tradition of male rulers and he did not want women in the future emulating Hatshepsut in this way. The most vital duty of the pharaoh was the maintenance of ma’at and honoring the traditions of the past was a part of this in that it maintained balance and social stability. Even though Hatshepsut’s reign had been successful, there was no way to guarantee that another woman, inspired by her example, would be able to rule as effectively. To allow the precedent of an able woman as pharaoh to stand, therefore, could have been quite threatening to Thutmose III’s understanding of ma’at.

Egyptian Soldiers

Σταύρος (CC BY)

Although the inner reliefs, paintings, and inscriptions of her temple were left largely intact, some were defaced by Thutmose III and others by the later pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE). By the time of Akhenaten, Hatshepsut had been forgotten. Thutmose III had replaced her images with his own, buried her statues, and built his own mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri in between Hatshepsut’s and Mentuhotep II’s. His temple is much smaller than either, but this was not a concern since he essentially took over Hatshepsut’s temple as his own.

Akhenaten, therefore, had no quarrel with Hatshepsut as a female pharaoh; his problem was with her god. Akhenaten is best known as the ‘heretic king’ who abolished the traditional religious beliefs and practices of Egypt and replaced them with his own brand of monotheism centered on the solar god Aten. Although he is routinely hailed as a visionary for this by monotheists, his action was most likely motivated far more by politics than theology. The Cult of Amun had grown so powerful by Akhenaten’s time that it rivaled the throne – a problem faced by a number of kings throughout Egypt’s history – and abolishing that cult along with all the others was the quickest and most effective way of restoring balance and wealth to the monarchy. Although Hatshepsut’s temple (understood by Akhenaten to be that of Thutmose III) was allowed to stand, the images of Amun were cut from the exterior and interior walls.

Hatshepsut’s ReDiscovery

Hatshepsut’s name remained unknown for the rest of Egypt’s history and up until the mid-19th century CE. When Thutmose III had her public monuments destroyed, he disposed of the wreckage near her temple at Deir el-Bahri. Excavations in the 19th century CE brought these broken monuments and statues to light but, at that time, no one understood how to read hieroglyphics – many still believed them to be simple decorations – and so her name was lost to history.

The English polymath and scholar Thomas Young (1773-1829 CE), however, was convinced that these ancient symbols represented words and that hieroglyphics were closely related to demotic and later Coptic scripts. His work was built upon by his sometimes-colleague-sometimes-rival, the French philologist and scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE). In 1824 CE Champollion published his translation of the Rosetta Stone, proving that the symbols were a written language and this opened up ancient Egypt to a modern world.

Champollion, visiting Hatshepsut’s temple, was mystified by the obvious references to a female pharaoh during the New Kingdom of Egypt who was unknown in history. His observations were the first in the modern age to inspire an interest in the queen who, today, is regarded as one of the greatest monarchs of the ancient world.

Tomb of Hatshepsut

Michael Lusk (CC BY-NC-SA)

How and when Hatshepsut died was unknown until quite recently. She was not buried in her mortuary temple but in a tomb in the nearby Valley of the Kings (KV60). Egyptologist Zahi Hawass located her mummy in the Cairo museum’s holdings in 2006 CE and proved her identity by matching a loose tooth from a box of hers to the mummy. An examination of that mummy shows that she died in her fifties from an abscess following this tooth’s extraction.

Although later Egyptian rulers did not know her name, her mortuary temple and other monuments preserved her legacy. Her temple at Deir el-Bahri was considered so magnificent that later kings had their own built in the same vicinity and, as noted, were so impressed with this temple and her other works that they claimed them as their own. There is, in fact, no other Egyptian monarch except Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) who erected as many impressive monuments as Hatshepsut. Although unknown for most of history, in the past 100 years her accomplishments have achieved global recognition. In the present day, she is a commanding presence in Egyptian – and world – history and stands as the very role model for women that Thutmose III may have tried so hard to erase from time and memory.

This article has been reviewed by our editorial team before publication to ensure accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards in accordance with our editorial policy.