For almost a century, King Tutankhamun has been the poster boy for Ancient Egypt. His death mask was sublimely, breathtakingly crafted over 3,300 years ago from 24 pounds of beaten gold, with eyeliner of lapis lazuli and eyes of quartz and obsidian.

It’s probably the most recognizable artifact we have from antiquity.

Once entombed in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, the mask has toured the world, entrancing audiences with its aura of opulence and millenia-old regal mystery.

“You know, if you ask a child from the age of eight and you tell him Egypt, and he will tell you King Tut,” Zahi Hawass, an Egyptian archaeologist and former antiquities minister, tells CNN. “I made a Skype last week to a school in the States. All the children ask about one thing, Tutankhamun.”

While ancient Egyptians crafted great monuments to their dead, wonders of granite and limestone including the Pyramids at Giza, modern Egyptians have been building a new home for Tutankhamun and his ancestors just over a mile away.

Something monumental of their own in glass and concrete.

Construction has taken eight years so far, the opening delayed multiple times, but the Grand Egyptian Museum isn’t called “Grand” for nothing.

At almost half a million square meters, it’s the size of a major airport terminal, with a price tag to match. Most of the huge cost has been met with loans from Japan.

The Egyptians badly want tourists back in the large numbers that the country hasn’t seen since before the country was gripped by political upheaval in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring.

This museum amounts to a calculated gamble – a $1 billion dollar bet on Tutankhamun. His treasures will be the star attraction when all finally arrive here next year.

This should be their last resting place.

A selection of Tutankhamun’s treasures have been on the road – off and on – since the 1960s. Among them, the Boy King as “Guardian Statue,” a proud figure, face and body painted black to symbolize the fertile silt of the Nile.

Another gold-covered statue shows Tutankhamun carrying a harpoon and wearing one of his many crowns. On the back of a golden throne, the young pharaoh appears in a tender marital portrait, king and queen bathed in the rays of the sun. And on a golden fan, he’s seen hunting in his chariot.

Tutankhamun’s portrait was always idealized, as it was on his famous death mask.

The reality may well have been rather different.

Images of his unimposing mummy, first revealed in 1925, show that Tutankhamun was probably a child of incest, standing about 1.65 meters (5 ft 5 in). Scientists think that he may well have had a clubfoot and buck teeth.

He was dead at 18 or 19 and Egyptologists still speculate about what killed him.

“When you go really deeply into the collections of the king, into the history of the king, you discover that he was a really important king,” says Tayeb Abbas, head of archaeology at the Grand Egyptian Museum.

“What is also important about the king is that his life and death are still a mystery. And that’s why people all over the world are still fascinated by King Tutankhamun.”

The creation of the new museum has taken almost as long as Tutankhamun’s lifespan. A winning design was chosen in 2003, with a facade or wall of semi-translucent stone, one kilometer long, that can be backlit at night.

The original architects were a small Dublin-based practise, Heneghan Peng, led by an American-Chinese architect, Shih-Fu Peng.

The Egyptian Revolution in 2011 delayed things and construction only began in earnest the following year.

CNN first caught up with the project six years later, in 2018, as the pyramid’s entrance took skeletal shape.

“It’s a new landmark that is being added to the complete view of the city of greater Cairo… for the first time the pyramids and the fantastic treasures of Tutankhamun will be eye to eye,” Tarek Tawfik, the former director general of the Grand Egyptian Museum Project, said at the time.

A visit to the museum in May 2020 revealed everything looking pretty much landscaped and ready.

But behind the scenes, it’s still a construction site – and Covid-19 hasn’t helped.

Going in, everyone had to have their temperature checked, including CNN’s team.

Like extras from a remake of “Ghostbusters,” gangs of workers wearing tanks of disinfectant on their backs were out spraying.

“We are working hard, despite Covid-19,” says Major General Atef Moftah, the army engineer who is the museum’s general supervisor. “We are taking precautions, sterilizing everything and everyone.”

Pharaohs and gods

On the ground, it’s easy to get a sense of how gargantuan this project really is.

The statue of Ramses the Great – the largest of all the museum artifacts – arrived in 2018 so they could build the atrium around the 13th century BCE pharaoh.

More than 20 meters high, crafted from 83 tons of red granite, he’s simply magnificent – even with his nose royally chipped and his stubby toes lightly coated in dust.

Egypt’s new one-billion dollar museum

02:27 – Source: CNN

The new museum is a far more dignified place to hang out than the polluted spot outside Cairo’s main railway station where Ramses used to stand.

His companions – on a grand staircase behind him – are mostly still under wraps.

There’ll be 87 statues of pharaohs and Egyptian gods on the steps. As visitors ascend, they’ll get a sweeping history of Ancient Egypt. Some 5,000 years of it.

Or at least they will when the museum finally opens.

“The project is scheduled to be finished by the end of this year,” says Moftah. “Then at the beginning of next year, we will work on the antiquities side of the project for four to six months. Hopefully by then, Covid-19 will be over and have left the world in peace.”

What was clear from CNN’s brief visit, as work to tidy up the vast spaces goes on, is that tourists may need to set aside two days to get around it.

Wandering through the museum, visitors may spot a familiar recurring motif.

Pyramids are everywhere. Upright and sometimes inverted, huge triangular designs built into the museum’s monumental structures and mosaic surfaces. And then there are the real pyramids – visible through gigantic windows. This is a museum with a view.

That Great Pyramid less than a mile away took roughly, it’s thought, 20 years to build, when Pharoah Khnum Khufu wanted to create a burial place for himself back in the 26th century BCE using more than two million granite blocks – each weighing over two and a half tons.

From architectural competition to planned opening in 2021, the Grand Egyptian Museum has also taken almost 20 years.

The museum is manifestly a matter of huge prestige for Egypt. In tandem with the building, an extraordinary program is underway to conserve every single one of Tutankhamun’s treasures.

The intention is to exhibit all of them together – for the very first time.

The Conservation Center for the Grand Egyptian Museum is the largest of its kind in the Middle East. It’s a seemingly endless corridor leading to no fewer than 10 different laboratories, all devoted to the art of conservation.

The labs themselves are enveloped in an almost monastic silence. The experts working within them need intense concentration, a good eye and a steady hand.

There are more than 5,000 artifacts to conserve from Tutankhamun alone. “His magnificent panoply of death,” as Howard Carter, the man credited with finding his tomb, once said.

Many items are being freshly conserved so that they can be shown for the very first time when the new museum opens.

Funding for some of this work comes from Tutankhamun’s golden legacy – income from exhibiting his treasures overseas.

“When I sent that Tutankhamun exhibit in 2005 to the States, Australia, Japan and London, I brought to Egypt $120 million to build the conservation labs. I never thought to see young Egyptians – geniuses with golden hands – returning every piece back,” says Hawass, the former minister of antiquities. “That was the first thing that captured my heart.”

Here in the labs can be found the lion goddess, Menhit, with nose and tears of blue glass, eyes of painted crystal. There’s the deity Ammut, part hippo, part crocodile, part lion – with teeth and red tongue of ivory.

The cow goddess, Mehet-Weret, is here too, represented in a pair of bovine figures, solar discs wedged between their horns.

There are also ritual couches that were apparently intended to speed Tutankhamun on his journey to the afterlife. After conservation, they remain in astonishingly good condition.

It’s a privilege to witness all this material before it goes under glass in the new museum.

And not everything was golden.

Tutankhamun was buried with some 90 pairs of his sandals. Some of rush and papyrus, others of leather and calf-skin.

Before conservation, one pair had partially rotted away, but even these were still somehow salvageable.

“We create a new technique by using some special adhesive,” says Mohamed Yousri, one of the conservators. “It’s condition was very bad, and I think it comes alive again.”

One pair – almost brand new, it seemed – is decorated with captured warriors, one Nubian, the other Asiatic. In these sandals, Tutankhamun could symbolically crush his enemies under foot every day.

“What we are doing here is re-discovering the collections of the king,” says Tayeb Abbas, the museum’s head of archaeology. “So we are doing the job which is really as important as it was done by Carter.”

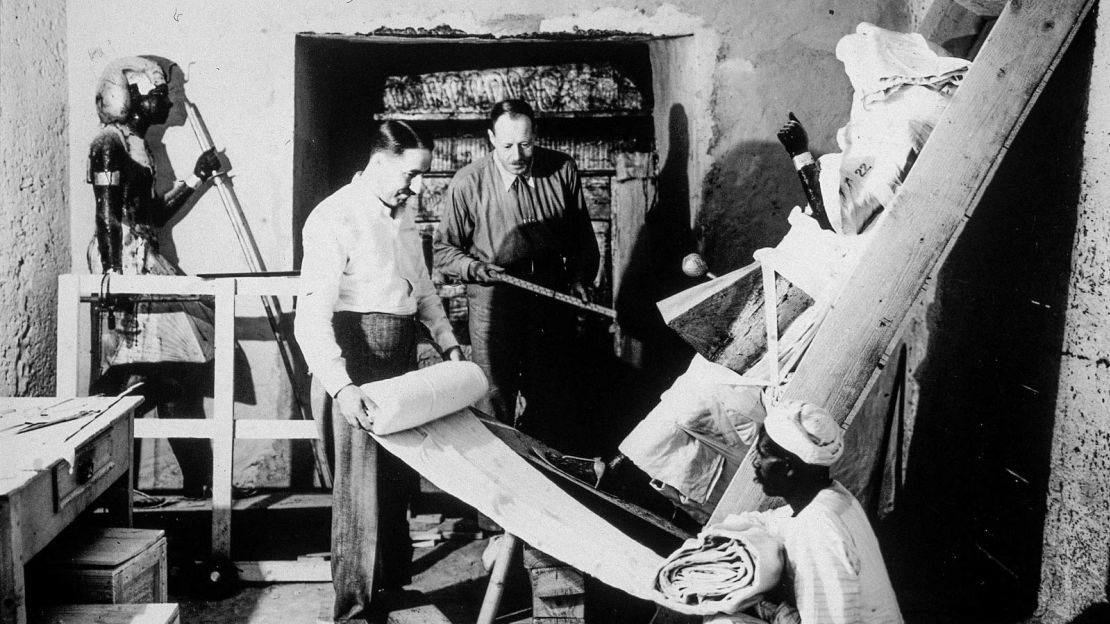

Howard Carter, an Englishman, was 48 years old when he made the discovery of his life in the Valley of the Kings, a pharaonic burial complex on the western banks of the Nile near the city of Luxor.

He would spend a decade – from 1922 to 1932 – recording the treasures and methodically clearing the tomb.

Without his doggedness, Tutankhamun might never have been found. And without Tutankhamun, we probably wouldn’t have a Grand Egyptian Museum.

“This king was unique,” says Hawass. “I think Howard Carter was so lucky to discover his tomb. And this is my opinion. This is the most important discovery, still, in archaeology.”

Carter’s archive is kept at the Griffith Institute, an Egyptology center at the UK’s Oxford University.

A meticulous, demanding man, Egyptology will forever owe him an immense debt. Carter’s clearance of the tomb was, for the time, exemplary.

Artifacts like the black and gold Guardian Statue were sprayed with protective paraffin wax. But now, almost a century later, the wax is being taken off.

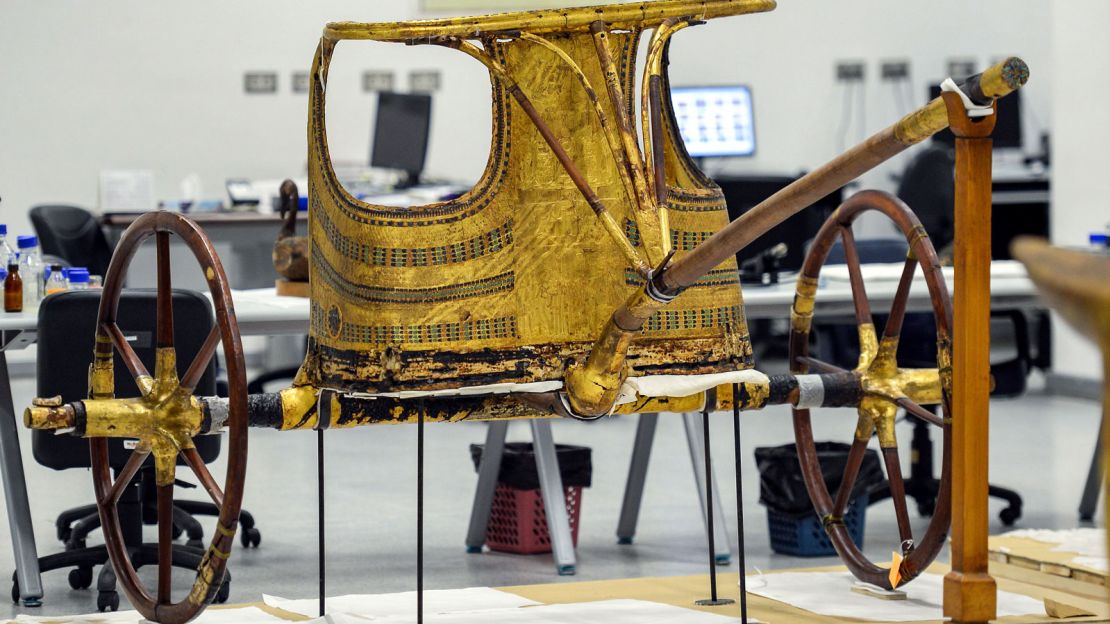

In the labs, a ceremonial chariot was having every little bit of wax winkled and teased out during CNN’s visit. Its old sheen was restored.

Tutankhamun’s outer coffin, meanwhile, has been fumigated for insects. Just conserving this one artifact has taken some eight months.

This is the first time the coffin has ever left the tomb in the Valley of Kings. And it won’t be going back there, a fact that not everyone’s happy about.

“To be honest, most of the people on the west bank were angry because of this,” says Abbas. “But when we took it out of the tomb, the people saw the bad condition of how the coffin was, people started to encourage us to get it back to how it looked like before.”

The local residents did win one campaign. They’re going to keep Tutankhamun’s mummy, even though, like the outer coffin, the authorities had coveted it for the new museum.

“The people of Luxor think that their grandfather should stay there,” says Hawass, the former minister of antiquities. “And I really do respect this. When we decided to move it a few months ago, all the people of Luxor disagreed with that. And this really actually made me happy. The mummy will stay there.”

Fifteen years ago, Hawass did manage to extract the mummy for a CT scan – but only for a day, barely enough time to incur the “mummy’s curse” – the supposed deadly consequence of moving King Tut’s remains, a legend that is said to have claimed the life of Carter’s financial backer Lord Carnarvon.

“When I went to scan the mummy and I took the mummy out of the coffin, I looked at his face,” Hawass says. “That is the most beautiful moment in my life. The discovery – November 4, 1922, 5,398 objects were found, excavated by Carter for 10 years. The curse. Lord Carnarvon died. All of that made the magic of King Tut!”

Everything, it seems, always comes back irresistibly to Tutankhamun. A century ago, only a few Egyptologists even knew his name. Now everyone does.

While the new Grand Museum will help preserve his status and many more of Egypt’s ancient artifacts, it’s reassuring to note that a piece of the country’s more recent history will not be overlooked.

Head into central Cairo and the salmon pink sandstone edifice of one of its most distinct landmarks is unmissable.

The Egyptian Museum of Antiquities – so beloved by Egyptologists – opened in 1902.

Inside is hall after hall of statuary and an ever-expanding collection. It’s here you can meet some of the Boy King’s relatives.

There’s Akhenaten, the so-called “heretic” pharaoh – Tutankhamun’s father. And an unfinished bust of his stepmother, the serene Nefertiti. His grandparents are here too – Yuya and Tjuyu were once a power couple.

“You know, Cairo Museum, you cannot close it even if you have the Grand Egyptian Museum,” says Hawass. “If you enter this museum, you smell the history. You smell the past and that’s why we are keeping it as it is.”

Of course, tourists always swiftly take the stairs to the first floor of the Cairo Museum. That’s where – for the time being – you can still find the death mask and the rest of Tutankhamun’s treasures

The display here has always seemed a bit dull. Beautiful but old-fashioned glass cases and drab lighting.

But then gold is still pretty stunning in any light.

There’s the solid 22-carat gold likeness of Tutankhamun that formed his innermost coffin. It measures just over six feet long, and weighs a hefty 108 kilograms (240 pounds) – about the same weight as Anthony Joshua, the heavyweight boxing champion.

More endearing perhaps, is a painted wooden sculpture of Tutankhamun, probably executed when he was in his early teens. This may have been a mannequin for his clothes.

Back in the labs, they have, in fact, been carrying out the first ever scientific study of Tutankhamun’s textiles, including a scarf or shawl several meters long that has somehow endured over the 3,300 years since his death.

The research is part of a joint Egyptian-Japanese project.

“Among the many objects from the Tutankhamun’s tomb, textiles are the most deteriorated materials,” says ancient textiles expert Mia Ishii, an associate professor at Saga University in Japan. “Therefore it was a request from the Egyptian government to work especially on the textiles from the beginning.”

More than 100 textile examples were recovered from the tomb and were evidently used in life. Among them is a tunic of some kind. Clearly visible is the design of a lotus flower – for ancient Egyptians, the symbol of eternal life.

Japanese experts have also been advising on the big move – from the Cairo museum to the new Conservation Center’s labs 10 miles away.

Back in 2018, CNN watched a ritual couch being bandaged up like a patient with sunburn. Traditional Japanese washi or tissue paper was applied to fragile areas of gold leaf.

A hunting chariot needed a bespoke crate and a lot of manhandling – almost enough men for a football team.

Tutankhamun’s chariots, they’ve discovered, were all made from a hardwood – elm – a tree not native to Egypt. The wood probably came from somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean more than 500 miles away.

Some artifacts are still revealing their secrets. A set of rods covered with gold leaf were a bit of a puzzle, but it’s now believed they were part of a sunshade for a ceremonial chariot – the oldest sunshade ever found.

One discovery, a dagger found with Tutankhamun’s mummy, was made with iron from a meteorite. Anything that fell from the heavens seems to have had special meaning for ancient Egyptians.

Another treasure is a fabulous pendant, covered with scarab beetles – the ancient Egyptian symbol for immortality.

Back in the 1920s, the pendant was photographed around the neck of a boy who was employed to supply Carter’s archaeological dig workers with water. This, so the story goes, is the child who found the tomb.

Clearing a space for his large water jar, he chanced on the first step – the first of a flight of sixteen down to the tomb.

His story is expected to feature in the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Back at the new museum, the Tutankhamun exhibition space isn’t yet open for viewing. What is known is that it’ll be massive, some 7,000 square meters.

The Egyptians expect two to three million visitors in the first year of opening, and up to seven or eight million in the longer term. That would make the new Museum among the top three most visited in the world.

We know that Tutankhamun died young and suddenly. And in death, the Golden Boy became a god – ancient Egyptians regarded gold as the flesh of the gods.

And of course, it’s that gold that dazzles us still – and will surely tempt some of us to visit Tutankhamun in his new home.