On August 4, 2020, about a month before Nadine Panayot was set to take over as the curator of the Archeological Museum at the American University of Beirut (AUB), the capital city of Lebanon was rocked by a devastating explosion of ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut. The catastrophic event caused an estimated 218 deaths, 7,000 injuries, and billions of dollars in property damages.

The blast was so powerful that it was felt as far as Cyprus, and the streets of Beirut were covered in glass from shattered windows. At the AUB museum, 17 large windows and 5 massive glass doors were destroyed, and 72 of the ancient glass vessels on display lay shattered on its gallery floor. Only two of the fragile artifacts made it out intact.

Having survived multiple earthquakes due to Lebanon’s location on the Levant fault line, and two world wars, these objects representing 2,000 years of history, from the early Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad periods, had seemed invincible. “For them to be gone in a fraction of a second was unbelievable,” says Panayot.

The display case at the Archeological Museum at the American University of Beirut before the explosion. Only two of the artifacts in the case survived the blast. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

The display case at the Archeological Museum at the American University of Beirut before the explosion. Only two of the artifacts in the case survived the blast. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

The shock of seeing these smashed objects did not deter Panayot, however. She knew that they could be saved using basic conservation techniques. With the help of more than a dozen international institutions and a group of volunteers, Panayot set out to repair the country’s shattered history, one glass fragment at a time.

The museum had the necessary funding for its restoration mission, but because of the financial crisis that has plagued the country since 2019, it was unable to use its financial resources to buy the basic material needed to handle archeological artifacts. When Panayot took over at the museum on September 1, she reached out to the Institut National du Patrimoine in Paris with whom she was already working on another project. “I needed at least some type of gloves, some type of masks, and especially acid free paper,” she says.

Just a few days later, Claire Cuyaubère, a French expert in glass and ceramics, landed in Lebanon with 100 cubic feet of recovery and restoration materials. “We were working with Claire around the clock on our hands and knees, trying to sift through the thousands and thousands of shards,” Panayot says.

After the explosion, a team sifted through the shattered glass on the gallery floor of the AUB museum separating fragments of ancient glass from shards of modern glass from the display cases. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

After the explosion, a team sifted through the shattered glass on the gallery floor of the AUB museum separating fragments of ancient glass from shards of modern glass from the display cases. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

It took a week for the team, under Cuyaubère’s guidance, to collect all the glass fragments on the museum’s floor. With the training that they received from Cuyaubère, the team gained a know-how that they previously lacked: being able to see the difference between the ancient glass and the modern glass of the gallery’s shelves and display cases. Ancient glass is much more opaque, but because the artifacts shattered into pieces of various shapes and sizes, sometimes telling the difference wasn’t so easy.

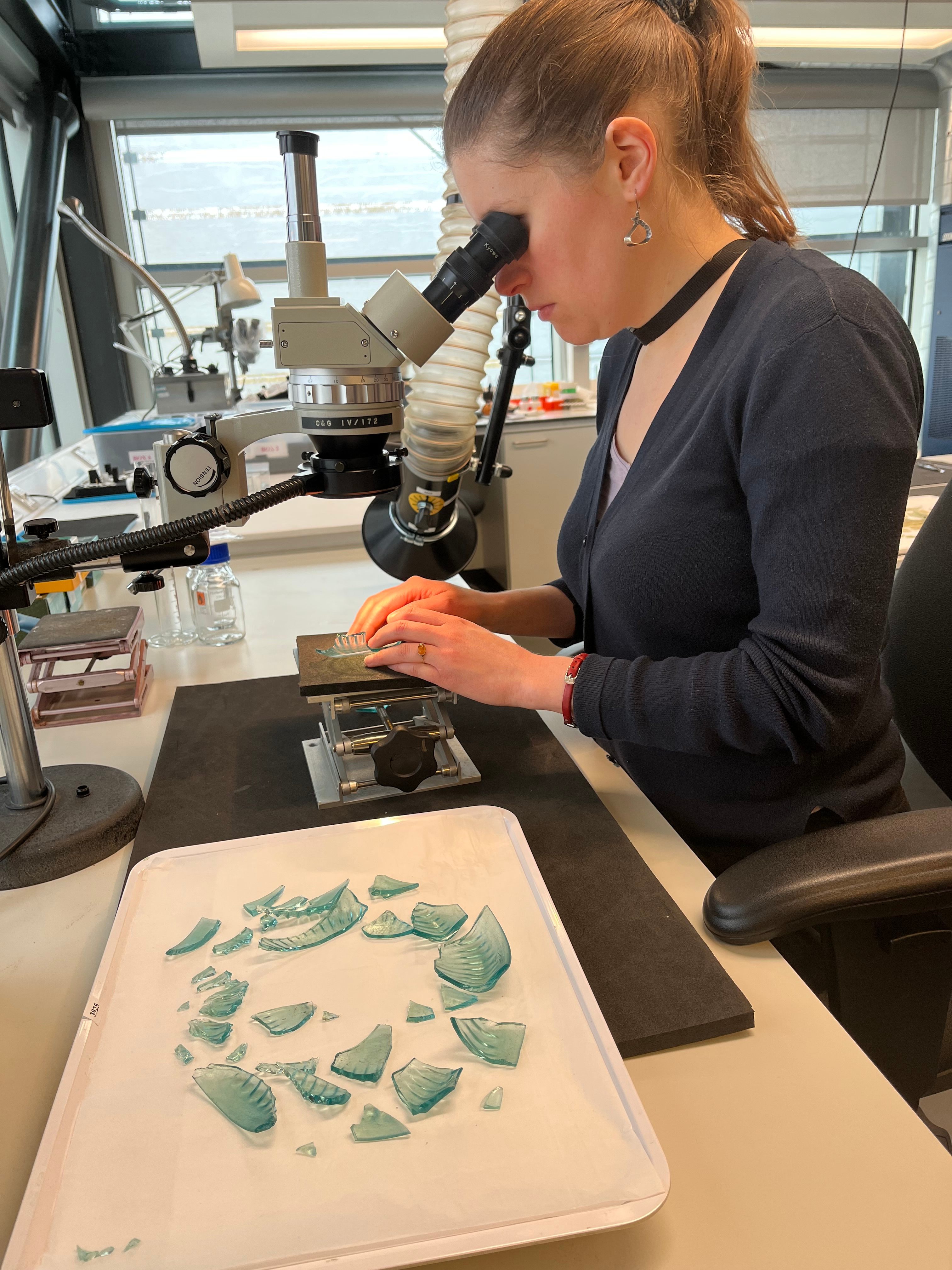

For the next nine months, a team from the AUB and the Institut National du Patrimoine in Paris worked for several hours a day sorting through the fragments and trying to reassemble the pieces that looked like they went together using conservation adhesive and Paraloid B72, an acrylic resin. This is what Cuyaubère called “the puzzling phase.” In the beginning, sorting through the glass proved complicated. “But eventually your eyes got trained for this exercise and we managed to do it,” says Panayot.

Claire Cuyaubère, a French expert in glass and ceramic conservation, worked to repair a Roman ribbed bowl from the first century. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Claire Cuyaubère, a French expert in glass and ceramic conservation, worked to repair a Roman ribbed bowl from the first century. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

So far, 24 ancient objects have been restored: 16 pieces at the AUB museum and eight more at the conservation lab at the British Museum in London, which offered a helping hand right after the explosion.

The completed vessels don’t look like they did hundreds of years ago, or even as they did a few years ago. Not every tiny shard of glass was recovered; these puzzles are still missing pieces. Conservators, like Duygu Çamurcuoğlu, senior objects conservator at the London institution, painstakingly filled gaps with adhesive to make the vessels structurally sound. But holes remain—intentionally. “We decided not to hide anything. We only made ‘gap fills’ for support,” says Çamurcuoğlu. These objects now carry new stories of the devastating damage they suffered, remnants of a tragedy that affected and displaced so many lives. “The scars are there,” she explains.

In the aftermath of the explosion, protests erupted across Lebanon against the government for its failure to relocate the dangerous chemicals, joining the civil protests that had already been ongoing across the country since 2019. The damaged and restored vessels carry with them that story, too.

The eight ancient vessels at the British Museum in London before they were reassembled. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

The eight ancient vessels at the British Museum in London before they were reassembled. © The Trustees of the British Museum and The Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

The eight vessels restored at the British Museum are currently featured in an exhibit called “The Shattered Glass of Beirut.” The exhibit, on display until October 23, is only temporary; the objects will then be returned to the AUB museum in Beirut.

For Panayot, restoring these objects is “a way of connecting the past to the present and giving them a new mission, of telling the story of what is happening to Lebanon today.” The shattered glass of Beirut not only represents the cultural heritage of greater Lebanon but also what it means to hold on to hope in the process of reconstruction. “I want visitors to carry with them the resilience of the Lebanese people,” Panayot says.