“With sunshine glinting on harness and lighting up the festive ribbons, the horses responded gallantly to the call, and amid a scene of great animation, the white-coated giant left its Midland home to join the enterprise and the perils of those that go down to the sea in ships, and to carry across mighty oceans the evidence of the prowess of the workers of South Staffordshire.”

This is how the Dudley Chronicle reported the spectacle of the 16-ton anchor, destined for the White Star “Titanic” ocean liner, beginning its journey from Netherton to Belfast on Monday 1 May 1911.

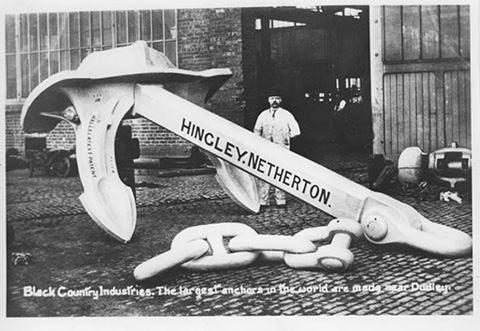

Since the 1840s the landlocked Black Country region had been at the centre of the manufacture of anchors and marine chain. Noah Hingley & Sons Ltd, Netherton Ironworks, was one of the leading companies and had made anchors for the White Star shipping company before, for Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic. The Titanic anchor, however, was the largest they had made for what would be the largest ship in the world. According to the Dudley Chronicle, the work was supervised by Mr Osborne, manager of the cable department at the Netherton works. Gangs of men worked hard forging over a thousand feet of chain for the ship. It is well known that Hingley’s were not responsible for making the whole of the anchor however. Walter Somers Ltd of Mucklow Hill, Halesowen, forged the shank of the centre anchor because they owned more powerful steam powered hammers. Rogersons Ltd of Newcastle-upon-Tyne also cast the huge steel head of the anchor. Hingley’s however, made the remaining parts and assembled the whole together, with the main anchor measuring 18 foot 6 inches long and 10 foot 6 inches wide.

The first journey the anchor made was to the nearby Lloyd’s Proving House, where the anchor and cable were tested for strength and safety. Once the tests on the anchor and chain were satisfactorily completed, the anchor could begin its next journey, to the LNWR (London and North Western Railway) Goods Station in Tipton Road, Dudley. To transport the anchor it was loaded onto a large heavy duty haulage cart, or dray, which was to be pulled by 8 horses, supplied by W. A. Ree, a sub-contractor to the LNWR, under the supervision of Chief Inspector Hobday of the LNWR. The journey would take the anchor through Netherton High Street, to Cinder Bank, onto Dudley town centre and down towards Tipton Road and the goods yard. With concern for the steep inclines en route Hingleys attached 6 of their own horses. A further 6 were made available to assist, which is why contemporary news reports quote the use of 20 horses. From the LNWR Goods Yard the anchor was transported by rail to Fleetwood in Lancashire, then by boat, the Duke of Albany, to Belfast. Its final journey to the shipyard was again by dray, pulled by horses.

The anchor’s journey to the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast attracted public and media attention. The Dudley Chronicle reported that photographers were positioned at every vantage point, including E Beech from Cradley Heath, whose images were later sold as postcards and are the images we closely associate today with the anchor’s journey. Beech had also famously captured images of Mary Macarthur’s visit to Cradley Heath in 1910 to support the women chainmakers strike. More innovative for the time, were “living pictures” of the works, horses and people, filmed by Mr G B Fraser, manager of the Provincial Cinematograph Theatre in New Street, Birmingham. According to the Dudley Chronicle the film footage was well received by cinema goers, especially finding the “spurt of the horses up the slope a stirring spectacle”. It would be amazing to see this footage, yet it’s almost certainly lost today. As the horses, adorned with May-Day decorations, were being attached to the dray, onlookers began to gather, “until a crowd of a thousand actually witnessed the anchor’s departure”, according to the Dudley Chronicle. One picture postcard shows some of the spectators in the street, as the horses begin to pull the anchor along on its journey. This image has always held significance for me because my great gran, Clara Cooksey always said that she was captured on the photograph, aged 10, with two of her brothers. The family lived in Washington Street at the time, where Hingley’s had an entrance to their Ironworks.

The largest anchor in the world, leaving Netherton, was a spectacle in its own right, yet it was the sinking of the Titanic, on its maiden voyage in 1912, which overtook any previous publicity for the building of this impressive ocean liner. The wreckage of the Titanic was only discovered on the seabed in 1985, 73 years after the ship sank, with underwater footage revealing the main anchor, still fixed on the bow. A link to the anchor remains on land however. In the 1970s Black Country Living Museum were given some chain from Lloyds British Testing in Netherton, with the claim that they had been part of the test length for the ship. After the ship sank, because of the public shock and interest, the chain remained in the yard, rather than being sent for scrap. A replica of the anchor, made in 2010, is also on public display in Netherton town centre.

The anchor wasn’t the only “Titanic” product made in the Black Country. Hingley’s also made two smaller anchors, 8 tons each. Stuart Crystal of Wordsley crafted glassware decorated with the White Star Line badge, the davits for the lifeboat mechanisms were made by Welin Lambie in Brierley Hill, Thomas Perry & Son of Bilston manufactured safes and Palethorpes of Dudley Port were proud to supply 18 Ibs of their famous “Royal Cambridge” sausages. It is, however, the images of the anchor being drawn through the streets of Netherton that have become iconic and continue to stir our interest today.