Assistant Curator Kerry Grist explores some of Thomas Edison’s lesser known inventions, and highlights some of the figures in Edison’s team who were key to making his ideas a reality.

Thomas Edison is a household name today due to his wide-ranging inventions and contributions to science. He was a prolific inventor, opening the world’s first research and development facility, Menlo Park laboratory, in 1876 to work solely on inventing things. His first major invention, the phonograph, received world-wide attention in 1878 and coined his nickname: ‘the wizard of Menlo Park’.

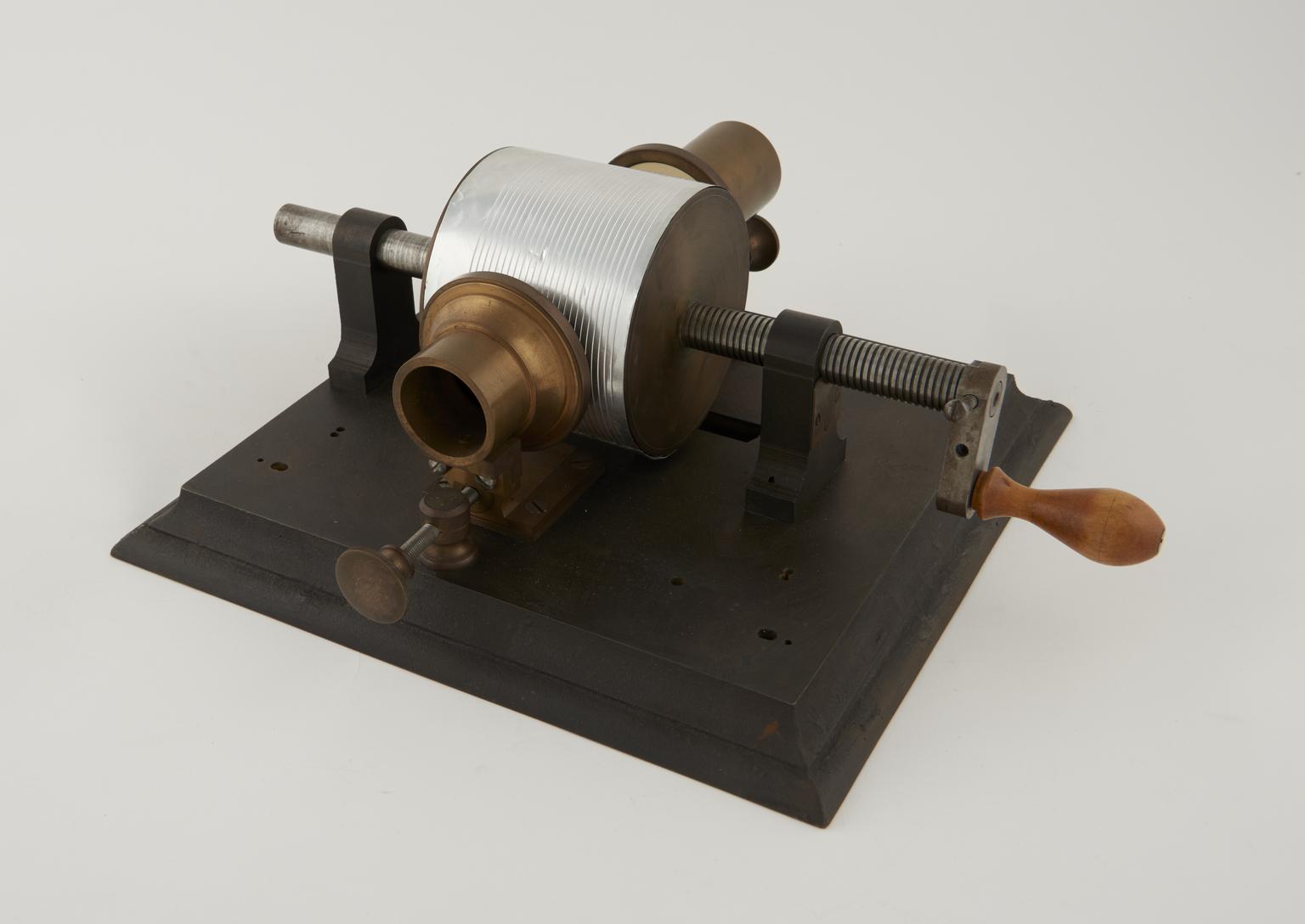

Replica of Edison’s original phonograph, 1877

Replica of Edison’s original phonograph, 1877

Edison didn’t slack in his work, holding 1093 patents at the time of his death in 1931. He did not stop once he had invented something, he was always working to improve his designs – not all of which were a success. When you’re busy inventing as a day job, not all your ideas will be good ideas!

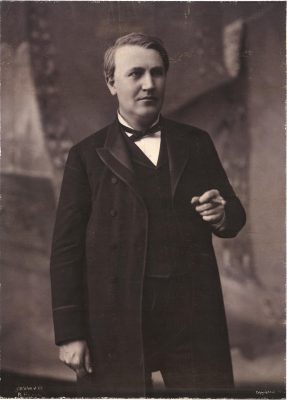

Thomas A. Edison (1847-1931)

Thomas A. Edison (1847-1931)

Unsurprisingly, with inventing on such a huge scale, Edison did not work alone. His staff were just as responsible for many of his inventions, despite Edison taking most of the credit.

The laboratories were known as “invention factories” due to the large number of projects happening at one time, and his staff were often doing a large bulk of the work in making his ideas a reality whilst Edison supervised.

For example, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, a British employee, is largely responsible for the “Kinetoscope” – the first device to show moving pictures.

In fact, one of Thomas Edison’s staff members was actually a prolific inventor in his own right, holding a number of patents himself.

Lewis Howard Latimer was a patent draftsman by trade, a skill which assisted Alexander Graham Bell in patenting the telephone prior to working with Edison.

Original incandescent electric carbon filament lamp, by Thomas Alva Edison made in 1879, with a bulb made by Ludwig K. Boehm.

Original incandescent electric carbon filament lamp, by Thomas Alva Edison made in 1879, with a bulb made by Ludwig K. Boehm.

Lewis also had a hand in one of Edison’s most famous inventions: the carbon filament lightbulb. Lewis held two patents relating to the carbon filament himself, and he wrote the first book on electric lighting in 1890 whilst working for Edison.

Original model of Edison’s patent electric preparatory pen for preparing stencils, 1875-1876.

Original model of Edison’s patent electric preparatory pen for preparing stencils, 1875-1876.

Edison’s “electric pen” is a much less known, and much less successful, example of his work.

It was one of the first inventions at Menlo Park, developed in 1875 and patented in August 1876 with the help of his British assistant Charles Batchelor.

The battery powered pen could make 50 punctures a second onto paper, creating a stencil of what you want to write (or draw) in multiple layers of paper.

The layers would then be inked over in an accompanying flatbed “duplicating press”, where a roller would press ink through the holes in the paper. This allowed many copies to be made at once, like an early photocopier.

Edison claimed over 5000 copies could be made at once.

Thomas Edison’s Autographic Printing patent (No. US180857), sheet 1

Thomas Edison’s Autographic Printing patent (No. US180857), sheet 2

As was Edison’s style, he submitted a patent for improvements to the pen in 1877.

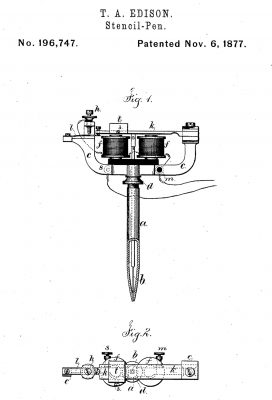

Thomas Edison’s Stencil-Pen patent (No. US196747)

Thomas Edison’s Stencil-Pen patent (No. US196747)

The pen was initially successful, winning a bronze medal at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. In 1877 it was officially endorsed in the UK by Charles Dodgson – AKA Lewis Carrol, the author of Alice in Wonderland – who had been an early adopter of the pen. He is known to have used the pen for a number of private writings, including his mnemonic document Memoria Technica for Numbers.

However, the design was limited by the battery requirement, as it could not compete with non-electrical, mechanical pens or the increasing popularity of the typewriter.

Despite a likely inflated advertising claim of selling over 60,000 pens, Edison ditched the idea in 1880, the same year his London agent wrote that ‘The day for the Electric Pen has passed’.

But this was not the end for the electric pen…

Edison Electric pen, c.1885

Edison Electric pen, c.1885

In 1887 Edison worked with Albert Blake Dick to market the “mimeograph“, a copying device that utilised the electric pen’s flatbed duplicating press; however, the electric pen itself was not featured in this product.

This iteration of Edison’s work remained popular until the 1960s, when modern photocopiers gradually made the technology obsolete. Edison allowed his name to be used as a marketing device, showing the power of his fame and popularity as an inventor.

The Edison Mimeograph duplicating machine, made by the Edison Mimeograph Company, London, c.1890s

The Edison Mimeograph duplicating machine, made by the Edison Mimeograph Company, London, c.1890s

The electric pen itself faded into obscurity as a tool for copying, but its design survived in an unexpected form. Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, made a small number of adaptations to Thomas Edison’s electric pen to create the ‘first’ electrical tattoo machine, for which he received a patent in 1891.

This revolutionised tattooing, allowing 50 skin perforations per second (the same as were achieved on paper) when previously only two or three were possible.

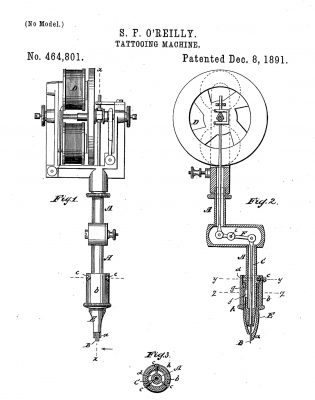

Samuel O’Reilly’s Tattooing Machine patent (No. US464801A)

Samuel O’Reilly’s Tattooing Machine patent (No. US464801A)

However, O’Reilly wasn’t the first to notice the relevance of Edison’s pen as a tattooing device, or the first to use electricity in a tattooing machine – he was just the quickest to get a patent.

As early as 1878 an anonymous letter was sent to an American newspaper – the Brooklyn Eagle – proposing the “teletattoograph” with a few minor adjustments to Edison’s design.

American Dime Museums had recorded “electrically tattooed” bodies since the 1880’s, including some of Samuel O’Reilly’s own work.

These tattoos may have been inked with earlier iterations of an electric pen adaptation, but they may also have been done using adaptations of William Bonwill’s electromagnetic dental plugger.

This device was essentially an electrified dental hammer or mallet used to ‘plug’ cavities – like modern day fillings – and is credited as the first electrically operated handheld implement.

Bonwill electromagnetic mallet, with Dr. M.H. Webb’s improvements, by the S.S. White Co., USA, 1880-1890. This was the first dental device to use electricity, patented by William Bonwill in 1873.

Bonwill electromagnetic mallet, with Dr. M.H. Webb’s improvements, by the S.S. White Co., USA, 1880-1890. This was the first dental device to use electricity, patented by William Bonwill in 1873.

Adapted dental pluggers are thought to actually have preceded adaptions of Edison’s electric pen, but there is little known about the timeline of events as tattoos were an underground, taboo subject at the time.

The device was never patented as a tattoo machine, so Samuel O’Reilly’s device has gone down in history as the first “official” electric tattoo machine (and kept the legacy of the electric pen alive!).

Both the dental plugger and Edison’s electric pen had influence over the creation of the electric tattoo machine, demonstrating that ideas and inventions don’t exist in a vacuum.

One idea can spark off a multitude of other ideas, and iterations of one or two things (successful or not!) can live on in something with an entirely different purpose.

You can explore more of Thomas Edison and his team’s inventions in the Science Museum’s Making the Modern World and Information Age galleries, and discover more objects on our collection online.